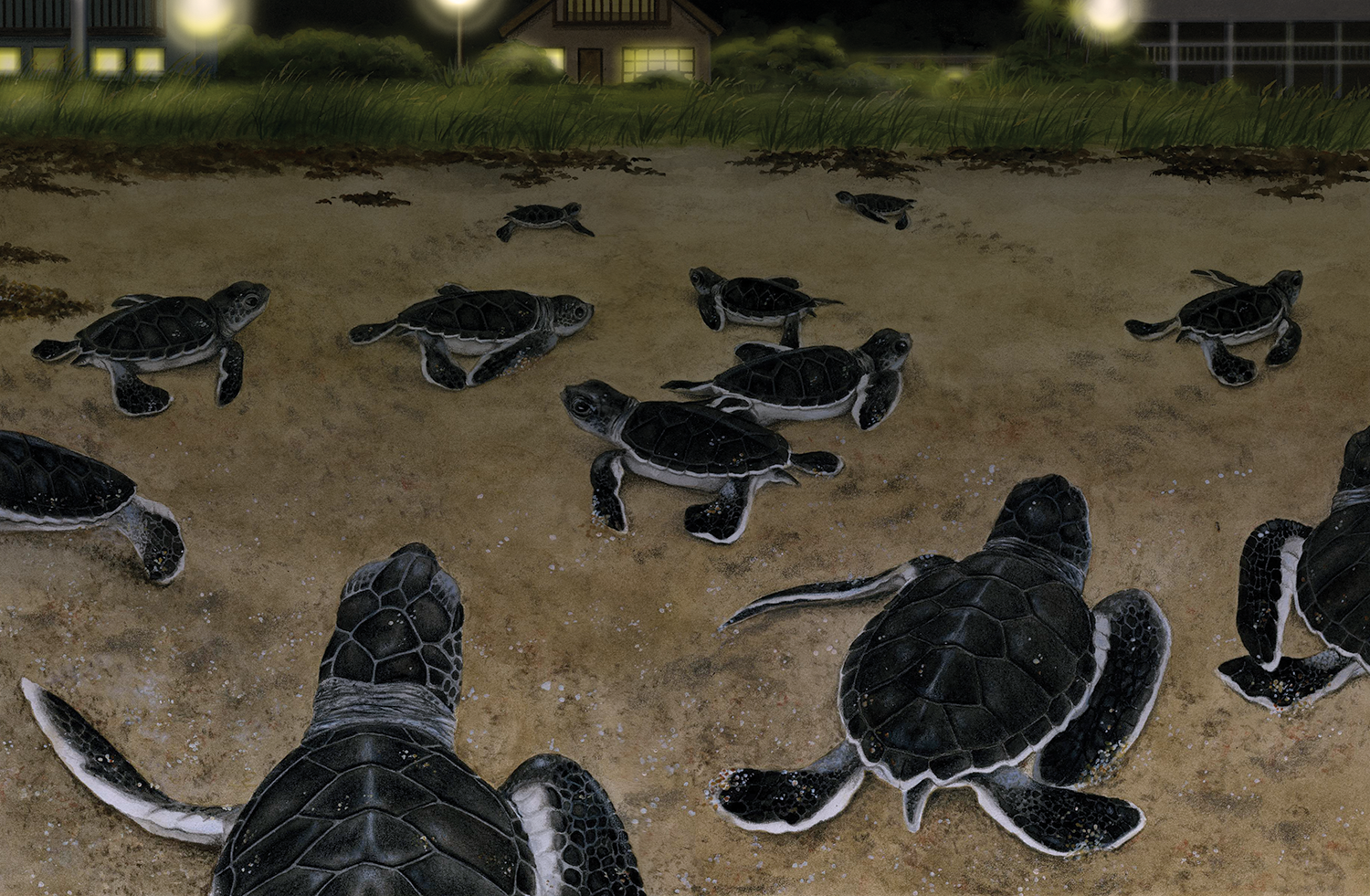

Illustration by Dawn Witherington

Introduction

In 1879 Thomas Edison said, “Let there be light!” and there was light. It did not take long for the night skies to light up across the globe. It was not much longer before scientists recognized and began to study the effects that bringing light into darkness would have on creatures other than humans – none more than sea turtles. The story of sea turtles and artificial lighting is a case study in the fruitful intersection of science, technology, and policy. As has been so often the case with sea turtle science and policy, all roads lead to Florida, and along its beaches.

The Early Science of Sea Turtle Orientation

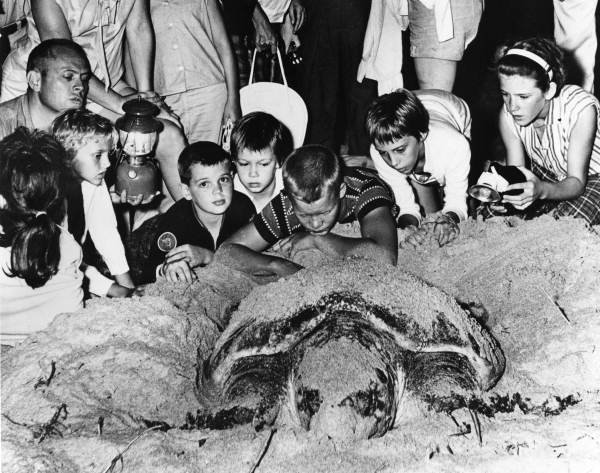

The science of animal orientation to external environmental stimuli had its beginnings in the early 19th Century but blossomed at the end of that century and beginning of the next, with much of the later inquiry focused on orientation to or away from light (phototaxis).[2] It did not take long for early researchers to explore the phenomenon in sea turtles. In 1907 and 1908, a Yale University Researcher named Davenport Hooker conducted crude experiments on loggerhead hatchlings at the Carnegie Institution’s Tortugas Laboratory in Florida’s Dry Tortugas.[3] Hooker made two prescient findings: 1) that the hatchlings naturally orient to diffuse light at the horizon, and 2) that “when the light of the lantern is thrown at night into one of the pens containing from 50 to 75 turtles, all orient and crawl toward the lantern and remain in the area lighted by it.”

Those two findings essentially, if simplistically, continue to explain the phenomenon of hatchling orientation to the sea—as well as the phenomena of disorientation and misorientation that contemporary sea turtle researchers and advocates know all too well. In 1922, working from the Miami Seaquarium, George Parker, Director of the Zoological laboratories at Harvard University, took some issue with these findings, concluding that slope and the broad open horizon (geotaxis) was an additional compelling factor in hatchling sea-finding.[4] In 1947, Robert Daniel and Karl Smith diminished the role of slope, and added additional context to the hatchling sea-finding mechanism, concluding that reflected light from the breaking surf serves as “the critical stimulus for both activating and guiding the ocean crawl.”[5]

From Orientation to Disorientation (and Misorientation)

Beginning in the late 1950s as night skies continued to brighten, the scientific research emphasis began to broadly shift toward the phenomenon of animal disorientation and misorientation across taxonomic groups—described as the “light trapping effect.”[6] The two phenomena are often confused or conflated—usually toward the single term of disorientation. They are distinct, however. Misorientation refers to an animal that moves deliberately toward a source of artificial light. [7] Disorientation refers to an animal that wanders from its original destination due to the presence of artificial light.[8] A wayward hatchling turtle can do both—on the same fateful journey.

Researchers also began to focus on the causes of light-induced disorientation and misorientation in sea turtles specifically. In 1958, working in Sarawak and Malaya, John Hendrickson noted his ability to guide hatchlings “at will” with flashlights in any direction.[9] In 1959, Archie Carr and his student Larry Ogren also observed this with leatherback hatchlings in Tortuguero, Costa Rica.[10] Hendrickson also described the reluctance of adult green turtles in Sarawak to come ashore in the presence of continuous artificial lighting, the degree of which varies by species. This would be born on in subsequent research as well.[11]

Early Warnings

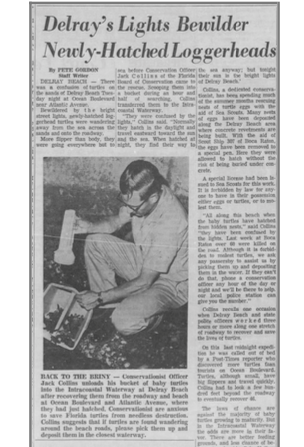

Perhaps the first alarm that would portend the future in Florida was reported in 1963 by University of Florida researcher Robert McFarlane in a short note in the herpetology journal Copeia.[12] Noting the proximity of coastal roads to urbanizing beachfront communities, in this case Fort Lauderdale, McFarlane observed a nest 30 feet from the surf and 100 feet from the adjacent highway. He reported that 95% of the hatchlings were unable to orient correctly and find the surf, finding the highway and certain death instead. Citing prior research, he attributed this to Ft. Lauderdale’s night glow and a mercury vapor streetlight on State Road A1A. Decrying the “disastrous effect of these rapidly developing resort areas adjacent to nesting beaches,” and noting the relative lack of hatchling mortality on adjacent undeveloped and unlighted beaches, he concluded, “[o]ne need only travel the shorelines of these beach resorts counting the hundreds of carcasses to realize that this is not an isolated example.” South Florida newspapers began to report on hatchling mortality as well, raising public awareness of the issue. In 1963, the Palm Beach Post reported: “In this era when baby turtles hatch they are sometimes confused by the glare of light in the sky over populated towns and cities and crawl inland to their death instead of toward the sea.”[13] In 1966, reporting on hatchling disorientation in Delray Beach, the newspaper headline read “Delray’s Lights Bewilder Newly-Hatched Loggerheads.”[14]

A news article in the Palm Beach Post highlights the problem of sea turtle disorientation on August 25, 1966. Photo credit: Blair Witherington

In 1974, Florida Atlantic University graduate student Thomas Mann quantified the extent of disorientation along six miles of South Florida beach from Fort Lauderdale to Delray Beach. He found that the “majority of hatchlings emerging on beaches nearby artificial lights sources were misoriented and usually headed inland.”[15] While not all of these meandered immediately to the highway and certain death, he speculated that the energy spent reorienting to the sea, would weaken them, and increase the likelihood of mortality as the hatchlings faced the perils of predation on the beach and in the surf zone, something that remains a continuing concern.

All the Light They Should Not See

It made sense that concerns over hatchling misorientation focused on Southeast Florida in the 1960s and early 1970s. Florida’s population doubled between 1960 and 1980, much of it centered on the tri-county Gold Coast of Dade, Broward and Palm Beach. Florida’s famed coastal highway State Road A1A, running parallel to the Atlantic Ocean, became Main Street for the rapidly developing South Florida beach towns, often forming a continuous path of development, with little but “welcome to” signs to distinguish one town from the next. In places the highway runs right along the water, providing the views that have helped to make it famous—and dangerous for sea turtles. Human public safety concerns dictated the increasing need for street lighting, and street lighting technology moved from incandescent to mercury vapor and eventually to sodium vapor.[16] Unfortunately, all these technologies share the part of the visible light spectrum that affects sea turtles, albeit to varying degrees. Subsequent research would begin to identify that part of the spectrum that most affects sea turtles, a precondition to adapting lighting technology to accommodate sea turtles.

Much of the rest of the State’s East and Gulf Coast barrier islands also began to boom in this period, if not so dramatically. Many of these barrier islands remained tenuously connected to the mainland by narrow two lane causeways with traffic-clogging drawbridges, and more distant from urban centers—some still disconnected from one another. Their time would come.

Photo credit: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

All the Light They Should Not See

Meanwhile, not content with the conclusion that light serves as the predominant mechanism to both orient and disorient sea turtle hatchlings, researchers continued to develop the science of sea-finding, focusing on both the color (wavelength) and brightness (intensity) of light. In 1968, David Ehrenfield, a student of Archie Carr, outfitted hatchlings with spectacles (if only there were photos!), and varied the spectrum of light the hatchlings were capable of seeing.[17] These experiments demonstrated that red light (the long-wavelength end of the spectrum) has a reduced effect on hatchling orientation relative to blue light at the low-wavelength end of the spectrum.[18] However, research also showed that light intensity could ultimately overwhelm color.[19] Subsequent research continued to confirm the spectral orientation of sea turtles toward long wavelength light.[20] These findings ultimately led to the prescription that would become the backbone of Florida sea turtle lighting policy: “Keep it Low; Keep it Shielded; Keep it Long.”[21]

A Broader Context: Light as Pollution

The growing concern over beach lighting and sea turtle behavior was not without context. The 1960s and 1970s was generally an era of environmental awakening. And while much of the emphasis on pollution was focused on air and water, light pollution began to receive global and national attention as well, first from astronomers, [22] but soon followed by wildlife scientists and advocates.[23] In 1987, the International Dark Sky Association, now DarkSky International, was established to advocate against light pollution.[24] Non-profit environmental education and policy advocacy was also emerging as a potent force in this period. In 1984, University of Central Florida researcher Paul Raymond published a report on hatchling disorientation supported by the Washington D.C.-based Center for Environmental Education and its “Sea Turtle Rescue Fund.”[25] The report reviewed the literature, assessed the current state of policy, and offered potential solutions.

A Policy Response Emerges

As renowned Florida historian Gary Mormino noted in his social history of Florida when describing the second half of the twentieth century, “[n]owhere was prosperity rearranging America with more force and speed than along Florida’s beaches.”[26] As barrier island populations swelled up and down both Florida coasts, beaches continued to light up and sea turtle hatchling mortality rose. This became particularly evident in Brevard County, which was continuing to experience massive growth due to the space boom. Newspapers continued to report on the annual highway carnage and the growing local environmental movement pressured political leaders to address the situation.[27] The epicenter of sea turtle nesting in Florida, Brevard’s south beaches host one of the most important nesting beaches in the Western Hemisphere.[28] Between 1978 and 1982, the two-lane causeway and drawbridge that led to Brevard’s South Beaches was replaced by a four-lane high-rise span facilitating greater access, spurring fears of rapid barrier island development.[29]

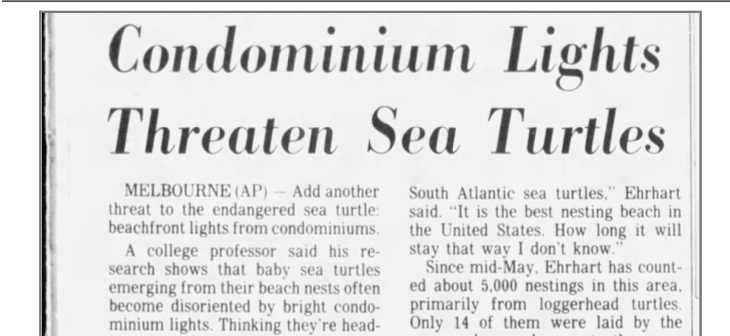

A news article from the Palm Beach Post highlights the threat of artificial lighting for Brevard County’s sea turtles on July 16, 1983. Photo credit: Blair Witherington

In 1982, in what appears to be the first formal local expression of public policy addressing sea turtles and lighting, Brevard County enacted a non-binding resolution requesting residents along the beach “to turn off those dwelling lights which face the shore areas in an effort to secure and protect the nests of sea turtles during the turtle crawl season.”[30] That resolution was followed by an enforceable beach lighting ordinance in 1985, one that would become the model for both the state and local governments in the coming years.[31] The ordinance, which appears to have applied only to the South Beaches, addressed both new development and existing development, with different treatment of each. It required that most lighting “not be visible from the beach,” that ocean-facing windows be tinted, and that certain fixtures be both low to the ground and low intensity, and shielded. All these requirements would eventually find their way into state law.

Perhaps serendipitously, at the time the Brevard ordinance was going into effect, a young researcher named Blair Witherington began his career in sea turtle conservation along Brevard County’s South Beaches. Witherington would go on to become one of the State’s (and world’s) leading experts on sea turtles. But in the summer of 1985, he spent his first graduate student field season assessing loggerhead and green turtle hatching production for his Master’s thesis at the University of Central Florida.[32] While he found that hatchling disorientation was significant, he also made the key finding that “the rate of hatchling disorientation was found to decrease following the enforcement of a regional ordinance restricting beachfront lighting.” Now looking back, Witherington credits the work of local natural resources and planning staff for their proactive efforts to craft a policy solution that the County’s decisionmakers could adopt.[33]

Blair Witherington, Paul Raymond, UCF Professor Llewellyn “Doc” Ehrhart, and Archie Carr gather on Melbourne Beach. Photo credit: Blair Witherington

Soon thereafter, other local governments took the cue and began adopting their own ordinances modeled after Brevard’s, beginning with the beach towns in Brevard County (1986 – Melbourne Beach, Indialantic, Cocoa Beach, Indian Harbor Beach), followed by many other Atlantic coastal counties and communities, then peninsular Gulf counties and communities, and later still, Panhandle communities.

Coming Next

Part II of this blog will track the growing interest of the State of Florida in sea turtle lighting policy in the 1990s, both through encouragement to local governments and through continued research and policymaking. Part II will also discuss the role the federal Endangered Species Act and the Florida Marine Turtle Protection Act played in beach lighting policy, through rulemaking and permitting, and litigation. The science of sea-finding would continue to develop, putting a finer point on preceding research while providing confidence to policymakers that their choices would make a difference. Lighting technology too would continue to evolve, offering greater opportunities for coexistence between humans and sea turtles on darkened beaches. Finally, a massive infusion of funding from the Gulf Oil Spill settlement became available to pursue retrofits of existing lighting in buildings across Florida’s beaches, offering a natural experiment on the impact that new lighting technologies could play in both increasing adult nesting on lighted beaches and reducing hatchling mortality.

Illustration by Dawn Witherington

References

[1] See Blair E. Witherington et al., Understanding, Assessing, and Resolving Light-Pollution Problems on Sea Turtle Nesting Beaches, Technical Report TR-2, Florida Marine Research Institute (1996).

[2] See Gottfried S. Fraenkel & Donald L. Gunn, The Orientation of Animals: Kineses, Taxes and Compass Reactions (Dover Publ’ns 1961).

[3] See Davenport Hooker, Certain Reactions to Color in the Young Loggerhead Turtle, 3 Papers from Tortugas Lab’y Carnegie Inst. Washington 69 (1911).

[4] See G. H. Parker, The Crawling of Young Loggerhead Turtles Toward the Sea, 36(3) J. Experimental Zoology 323 (1922).

[5] See Robert S. Daniel & Karl U. Smith, The Migration of Newly-Hatched Loggerhead Turtles Toward the Sea, 106(2756) Sci. 398, 398–99 (Oct. 24, 1947).

[6] See Frans J. Verheijen, The Mechanisms of the Trapping Effect of Artificial Light Sources Upon Animals, 13 Archives Néerlandaises de Zoologie, 1–107 (Jan. 1, 1960).

[7] See Blair E. Witherington & R. Erik Martin, Understanding, Assessing, and Resolving Light-Pollution Problems on Sea Turtle Nesting Beaches, Technical Report TR-2, 13 (Florida Marine Research Institute,1996).

[8] See id.

[9] See John R. Hendrickson, The Green Sea Turtle: Chelonia Mydas (Linn.) in Malaya and Sarawak, 130(4) J. Zoology 455, 455–535 (June 1958).

[10] See Archie Carr & Larry Ogren, The Ecology and Migrations of Sea Turtles: 3 Dermochelys in Costa Rica, 1958 Am. Museum Novitates 1(Aug. 5, 1959).

[11] See Michael Salmon, Artificial Night Lighting and Sea Turtles, 50(4) Biologist 163, (Aug. 2003).

[12] See Robert W. McFarlane, Disorientation of Loggerhead Hatchlings by Artificial Road Lighting, 1963(1) Copeia 153 (Mar. 30, 1963).

[13] See Protecting Turtles is Problem, Palm Beach Post, July 21, 1963.

[14] See Pete Gordon, Delray’s Lights Bewilder Newly-Hatched Loggerheads, Palm Beach Post, Aug. 25, 1966.

[15] See Tom M. Mann, Impact of Developed Coastline on Nesting and Hatchling Sea Turtles in Southeastern Florida (Mar. 29, 1977) (M.S. thesis, Florida Atlantic University) (on file with the Florida Atlantic University Digital Library).

[16] See John A. Jakle, City Lights: Illuminating the American Night page (Johns Hopkins Univ. Press 2001).

[17] See David W. Ehrenfeld & Archie Carr, The Role of Vision in the Sea-Finding Orientation of the Green Turtle (Chelonia Mydas), 15(1) Animal Behav. 25, 25-36 (1967).

[18] See N. Mrosovsky & Sara J. Shettleworth, Wavelength Preferences and Brightness Cues in the Water Finding Behaviour of Sea Turtles, 32(4) Behav. 211 (Jan. 1, 1968).

[19] See N. Mrosovsky & Sara J. Shettleworth, Wavelength Preferences and Brightness Cues in the Water Finding Behaviour of Sea Turtles, 32(4) Behav. 211, (Jan. 1, 1968); Robert S. Daniel & Karl U. Smith, The Sea-Approach Behavior of the Neonate Loggerhead Turtle (Caretta Caretta), 40(6) J. Compar. & Physiological Psych. 413 (Dec. 1947).

[20] See A. M. Granda & P. J. Oshea, Spectral Sensitivity of the Green Turtle (Chelonia Mydas Mydas) Determined by Electrical Responses to Heterochromatic Light, 5(2) Brain, Behav. & Evolution 143 (1972); D. H. Levenson et al., Photopic Spectral Sensitivity of Green and Loggerhead Sea Turtles, 2004(4) Copeia 908 (Dec. 15, 2004).

[21] See FWC Sea Turtle Lighting Guidelines (Dec. 2018), https://myfwc.com/media/18511/seaturtle-lightingguidelines.pdf.

[22] See Kurt W. Riegel, Light Pollution: Outdoor Lighting Is a Growing Threat to Astronomy, 179(4080) Sci. 1285, (Mar. 30, 1973).

[23] See Frans J. Verheijen, Photopollution: Artificial Light Optic Spatial Control Systems Fail to Cope with. Incidents, causation, remedies, 44(1) Experimental Biology 1 (1985).

[24] See Tim Hunter, The Birth of DarkSky (IDA) and a Lifelong Mission Fighting Light Pollution, DarkSky (Nov. 10, 2013), https://darksky.org/news/the-birth-of-ida-and-a-lifelong-mission-fighting-light-pollution/.

[25] See Paul W. Raymond, Univ. Cent. Fla., Sea Turtle Hatchling Disorientation and Artificial Beachfront Lighting (Ctr. for Env’t Educ. 1984).

[26] See Gary R. Mormino, Land of Sunshine, State of Dreams 322 (Univ. Press of Fla. 2008).

[27] See Condo Lights on Beaches Imperil Baby Sea Turtles, Fla. Today, July 16, 1983.

[28] See Llewellyn M. Ehrhart & Paul W. Raymond, Loggerhead (Caretta Caretta) and Green Turtle (Chelonia Mydas) Nesting Densities on a Major East-Central Florida Nesting Beach, 23(4) Am. Zoologist 963 (1983);

Llewellyn M. Ehrhart et al., Long-Term Trends in Loggerhead (Caretta Caretta) Nesting and Reproductive Success at an Important Western Atlantic Rookery, 13(2) Chelonian Conservation & Biology 173(Dec. 1, 2014).

[29] See Melbourne Causeway Bridge History, Wikipedia (Mar. 30, 2023, 7:31 UTC), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Melbourne_Causeway#Bridge_history.

[30] See Unnumbered Resolution of Brevard County Commission. August 5, 1982 (on file with the author).

[31] See Brevard County, Fla., Code § 85-15E (1985) (emergency ordinance related to the protection of sea turtles).

[32] See Blair E. Witherington, Human and Natural Causes of Marine Turtle Clutch and Hatchling Mortality and Their Relationship to Hatchling Production on an Important Florida Nesting Beach (1986) (M.S. thesis, University of Central Florida) (on file with STARS, University of Central Florida).

[33] See Video Interview with Blair E. Witherington, Senior Sea Turtle Conservation Biologist, Archie Carr Ctr. for Sea Turtle Rsch., Univ. of Fla. (Dec. 13, 2023) (available from authors).

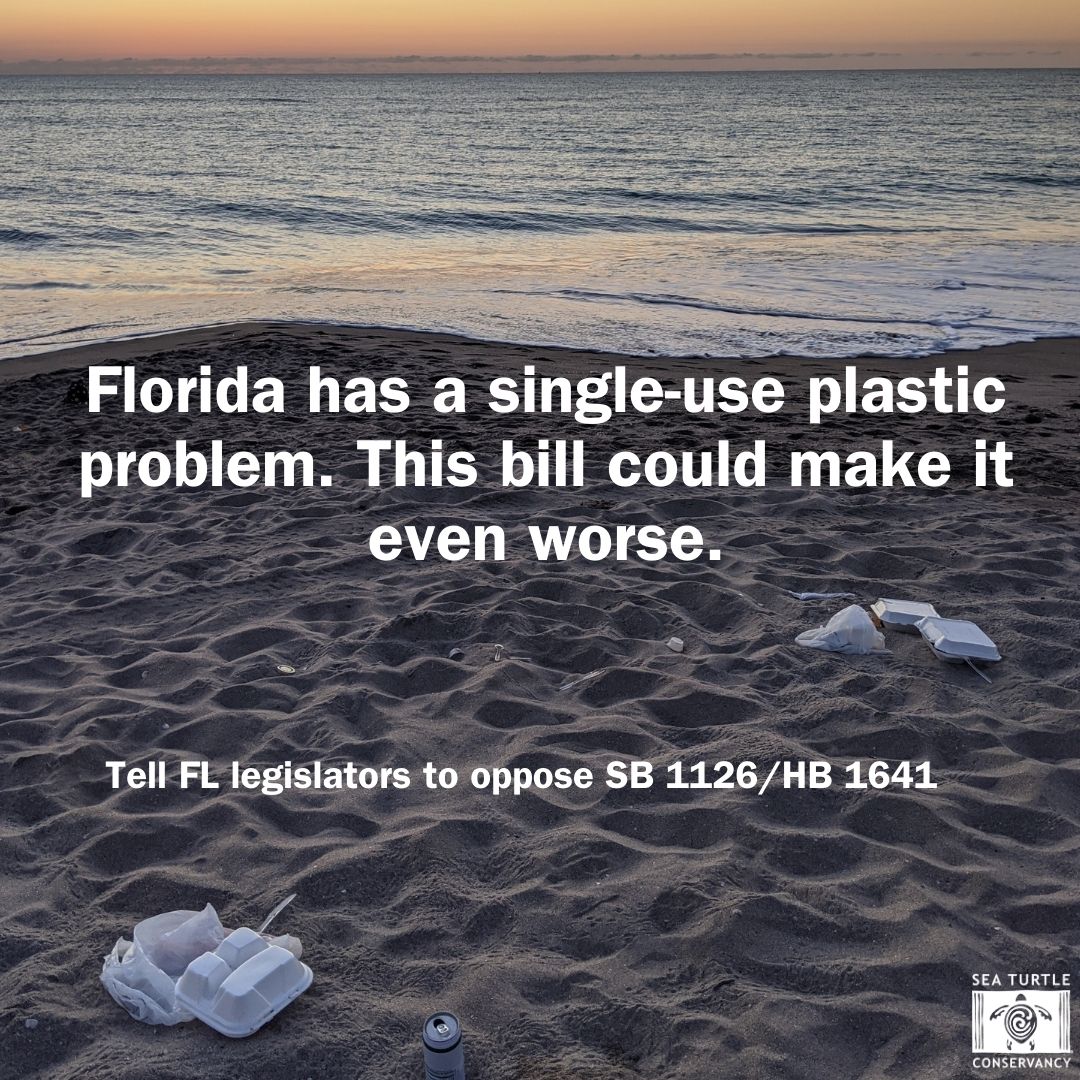

From November through March, STC conducted outreach around several bills filed during the Session that could have impacted Florida’s sea turtles and habitats. One of the most pressing was S.B. 1126/H.B. 1641 – Regulation of Auxiliary Containers, a bill that would have prevented all local governments in Florida from regulating any type of single-use container. This would have included single-use plastic, glass, polystyrene (commonly known as Styrofoam), and other materials. These regulations already exist in more than 20 local governments across the State and in some state parks, including Itchetucknee Springs, and directly prevent trash from polluting our waterways and harming wildlife.

The bill gained traction quickly. Once the bill was approved in its first House and Senate committee stops, STC and the environmental community rallied together to garner opposition to the bill. While we try to do this sparingly, STC sent several action alerts through social media, our website, and our e-newsletter urging our followers to contact committee members to vote “no” on the bill. On February 6, when the Senate version was scheduled to be heard in the Community Affairs Committee, STC Policy Coordinator Stacey Gallagher and Membership Coordinator Evan Cooper traveled to the Capitol in Tallahassee to speak against the bill. Representatives from the Florida Springs Council, the Surfrider Foundation, Ocean Conservancy, Oceana, and additional north Florida springs groups also traveled to speak at the meeting. However, once we sat down in the committee meeting, the committee chair announced that the bill was “temporarily postponed” by the bill sponsor. Because the committee was not scheduled to meet again for the rest of the Session, the Senate version of the bill was effectively dead. We believe that this positive development would not have occurred without the strong level of opposition waged by our partners and supporters.

STC Development and Policy Coordinator Stacey Gallagher and Membership Coordinator Evan Cooper pose with representatives from the Surfrider Foundation, the Florida Springs Council, and North Florida springs groups at the Florida Capitol on Feb. 6.

Unfortunately, the following week on Feb. 14, the House version of the bill was scheduled to be heard in the State Affairs Committee. STC and its partners again contacted legislators to educate them about the potential harms of this bill and urged our followers to do the same through action alerts. Luckily, the same result occurred in this meeting as the Senate version – the bill was temporarily postponed by the sponsor as soon as the meeting began. With this action, S.B. 1126/H.B. 1641 – Regulation of Auxiliary Containers was defeated, and local ability to regulate single-use containers was preserved.

Another concerning bill that STC and its partners advocated against was S.B. 738/H.B. 789 – Environmental Management. If passed in its original form, the bill would have required Florida citizens or nonprofits to pay the attorney fees for the prevailing party if they challenged a State environmental decision and lost. The bill also called for the State’s Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) and water management districts to conduct a “holistic review” of their coastal permitting processes and permit programs in order to “increase efficiency” within each program. Although “efficiency” in government permitting programs seems like it would be a good thing, used in this context, “efficiency” could have meant reducing important checks and balances in place to protect Florida’s natural resources, including our beaches and waterways. Currently, state regulations are in place that dictate the timing, location, and type of coastal construction that can be completed on Florida’s beaches to ensure that it does not harm federally-protected sea turtles and their habitat. If this bill were to have passed as written, these important barriers could have been weakened, leading to further improper development on Florida’s beaches and putting our sea turtles and largest economic driver at risk. STC is happy to share that with strong advocacy by our followers who responded to our action alerts and our partners, the harmful sections in the bill containing the fee-shifting provision and the “holistic review” of permitting processes were taken out of the bill through amendments.

Similar to the previous bill, S.B. 298/ H.B. 1079 – Local Government Coastal Protections would have taken away local governments’ ability to regulate building in coastal high hazard zones to the State. It also would have invalidated existing coastal building regulations that were already in place. Luckily, the House version of this bill did not move forward and the Senate version was amended to remove the harmful provisions regarding coastal high hazard building regulations.

Finally, STC also advocated for the passage of S.B. 602/H.B. 321 – Release of Balloons. Although many Floridians participate in balloon releases as part of a celebration or to honor a loved one, once balloons are released, they can travel thousands of miles before landing. When a balloon bursts and lands in the ocean, sea turtles and other marine wildlife often consume it because of its resemblance to jellyfish. Sea turtles are unable to regurgitate, so once the balloon enters the digestive tract, it can cause an impaction that can lead to death. As Florida Statute currently reads, residents can release up to ten balloons per day, with an exception for biodegradable balloons, which is not scientifically sound. This bill closed this unfortunate loophole and re-classified balloons as litter, which triggered a $150 fine penalty for citizens who intentionally released balloons.

Balloons are one of the most common types of litter found by marine turtle permit holders on the beach. Photo credit: DB Ecological Services, Inc.

After the bill was filed, it received near-unanimous support in all of its committees and in the full House and Senate. STC, in collaboration with our coastal and ocean partner organizations, informed various audiences about the importance of the bill’s passage and advocated for its approval. As of May 13, the bill has been approved by the Legislature and awaits Governor DeSantis’ approval. STC sent a letter to the Governor urging him to sign it into law; we are hopeful that he will sign it to protect Florida’s beaches and wildlife from harmful balloon litter.

It wasn’t all good news that came from the 2024 Session, however. On May 15, Governor DeSantis signed H.B. 1645 – Energy Resources into law. This law prevents local governments from approving the placement of natural gas facilities, removes the State’s clean energy infrastructure goals, repeals the Florida Energy and Climate Protection Act, prohibits offshore wind farms in Florida, and reduces opportunities for public participation on the siting of gas pipelines. The Governor also signed S.B. 1526: Local Regulation of Nonconforming and Unsafe Structures into law in March. This law prevents local governments from setting density limitations on redevelopment in fragile coastal areas. These laws are just two examples highlighting that our work to protect Florida’s sea turtles is not done.

Although STC and its partner organizations were largely defending against problematic policies this Session, nearly all of our priority bills received the outcome that we were aiming for. This was only possible through our close partnership with the Florida environmental community, direct communication with legislators, and our public-facing outreach. We are so grateful to our large network of dedicated sea turtle supporters who spent time learning about these issues and wrote emails, made phone calls, or shared about these bills on social media. Your advocacy and passion for Florida’s sea turtles made an enormous difference during the 2024 Legislative Session.

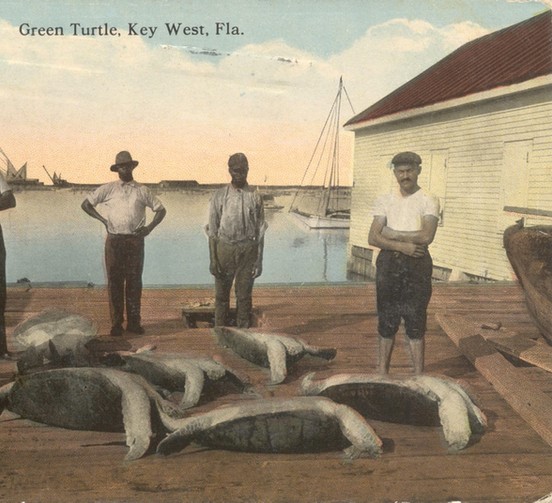

Photo credit: State Archives of Florida.

Introduction

In the early 1970s, Florida continued to struggle with managing sea turtles as a fishery, but the writing was on the wall. A booming conservation movement and increasingly sophisticated science, coupled with depleted stocks, led to the demise of the fishery. By the end of the 1970s, sea turtles were a “fishe” no more.

The Early 70s: From Commercial Fish to Protected Species – The Beginnings of Modern Florida Sea Turtle Conservation Policy

1970 mark a watershed year in the development of Florida sea turtle policy, and the beginning of the end of a legal fishery in Florida. The progenitor of what would become the Sea Turtle Protection Act began to take further shape with substantial amendments to Section 370.12, the statewide law first adopted in 1941.[i] The 1970 statute increased the fines for prohibited activities associated with nests and eggs on the beach (from $100 to $600), banned import and trade in “young sea turtles,” signaling an end to hatchery and “head-start” programs in Florida, and added leatherbacks, trunkbacks, hawksbills and Atlantic ridleys to the prohibition on take of nesting turtles and turtles within ½ mile of the shore during the nesting season. The new law also obligated the State to begin to set aside nesting beaches for conservation to control the impact of predation on nesting success (the first time in law that predation had been recognized as an issue). Finally, it created an administrative process for the State’s Department of Natural Resources to establish legal size limits, instead of relying on legislation to accomplish this management tool. All told, 1970 may be the year that marks the Sea Turtle’s transition from fisheries law to protected species law. It appears to be the first time the word “extinction” is used in state law in reference to sea turtles.

The issue of creating a minimum size limit became a contentious one, because the science for determining that size had not been established. In fisheries management, size limits are in part used as a proxy for sexual maturity and reproductive capacity. At the time the policy debate over minimum size for legal green turtle take was playing out in Tallahassee, the age, and hence size, for the species’ reproductive maturity had not been established. Nonetheless, charged by the 1970 legislation with establishing these limits, the staff of the State Board of Conservation, led by its Director of Research Robert Ingle, recommended a carapace length limit of 31 inches for Green Turtles on the Atlantic Coast and 26 inches on the Gulf Coast. At a contentious meeting of the Governor and Cabinet, which approved Board of Conservation rules, Ingle was grilled on the science for these carapace lengths, and admitted he had none – that it was essentially a compromise to keep the fishery open.[ii] At that same meeting a politically connected graduate student presented data from the Atlantic Coast on the limited green turtle nesting that occurred there and stated he had never seen a nesting green turtle less than 39 inches. Frustrated with Ingle and Board Staff, the Governor and Cabinet raised the limit to 41 inches for the Atlantic, while maintaining it at 26 inches for Gulf. It would not be until the early 1980’s that sea turtle biologists could conclude with some certainty that sexual maturity in green turtles and other species could take decades.[iii]

In 1971, Section 370.12 was again amended, this time to extend the reach of the prohibition for in-water take for all species from within ½ mile of the shoreline to within the “Territorial Waters of the State” (3 statute miles on the Atlantic Coast and 3 “leagues” or 9 nautical miles on the Gulf Coast).[iv] This prohibition applied to Loggerheads, Trunkbacks, Leatherbacks, Hawksbills and Ridleys during the nesting season. The same spatial expansion was applied to Greens, but it applied year-round to the entire East Coast, except the Florida Keys. This statute effectively ended the take of Green Turtles on Florida beaches and in Florida waters along the Atlantic Coast, except in Monroe County, where the 41-inch carapace length the Governor and Cabinet had previously established, was required to harvest Greens. Green turtles on the Gulf Coast could still be harvested but could only be taken when the carapace length exceeded 26 inches, a nod to the limited fishery that was hanging on in Cedar Key, Florida, where the Greens gathered to forage, but not to nest.[v]

Bessie Gibbs, owner of the Island Hotel in Cedar Key, holds a green turtle in 1963. Photo credit: Cedar Key Historical Society Museum.

Context Is Important: Emerging Sea Turtle Conservation Law and Policy at The Federal and International Level

While sea turtle conservation and fishery management approaches were diverging, events were unfolding internationally and in Washington that suggested the noose was tightening on the Florida sea turtle fishery. As early as 1963, negotiations had begun on an international agreement to protect endangered and threatened wildlife.[vi] The scientific basis for these negotiations came from the work of International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), an international conservation organization, which created the “Red Data Book,” an inventory of the conservation status and extinction risk of species worldwide begun in 1964.[vii] Archie Carr was asked to chair the Marine Turtle Specialist Group, in order to provide the science for the consideration of the inclusion of sea turtles in the Red Data Book, which occurred in 1968.[viii] IUCN’s efforts would set the stage for the 1973 passage of the global Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), and the eventual inclusion of all species of sea turtles on the lists that restricted or prohibited trade. In 1973, the Florida legislature passed a resolution encouraging the U.S. Government to “seek an international convention and agreement for the protection of the Green Sea Turtle.”[ix] Clearly the tide had turned.

In the United States, there was growing public interest and increasing concern over the survival of endangered wildlife. In 1966, Congress passed the “Endangered Species Preservation Act,” the first federal legislation on endangered species.[x] It required listing but did not create substantive obligations. In 1968, the first species were listed, including three reptiles, but no sea turtles. In 1969, the Endangered Species Preservation Act was renamed the Endangered Species Conservation Act and extended its protections to species “threatened with worldwide extinction.”[xi] In 1970, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed three species: the hawksbill, the leatherback and the Atlantic ridley, as “threatened with worldwide extinction.”[xii] This restricted importation of these species but did not impose domestic obligations. Those obligations would come in 1973, with the passage of the Endangered Species Act as we now know it.

Conclusion

By the early 1970s, the Florida sea turtle fishery had been so depleted that it ceased to be of commercial interest for all but a handful of fishers in Cedar Key on Florida’s Gulf Coast. Interest in sea turtle aquaculture, once a promising avenue for research, had also diminished. The 1973 federal Endangered Species Act, and the 1973 International Convention on Trade in Endangered Species effectively ended both.

Coming Next

Our next blog will depart from a chronological narrative of sea turtle law and policy and focus on the history of the Florida’s approach to lighting policy. Scientific advancement has allowed us to deeply understand the role light plays in adult and hatchling orientation, both in the water and on the beach. As Florida’s beaches developed, the night skies lit up, sea turtles suffered, and the State searched for an appropriate policy response.

Digging Deeper

Blair E. Witherington, Sea Turtles: an extraordinary natural history of some uncommon turtles (2006).

Alison Rieser. The Case of the Green Turtle: An Uncensored History of a Conservation Icon (2012).

Frederick D. Rowe, The Man Who Saved Sea Turtles: Archie Carr and the Origins of Conservation Biology (2007).

Chris Wold, The status of sea turtles under International environmental law and International environmental agreements, 5 J. of Int’l. Wildlife L. & Pol’y. 11–48 (2002) (DOI: 10.1080/13880290209353997).

Stephen P. Geiger, In Memoriam Robert M. Ingle 1917-1997. Journal of Shellfish Research, vol. 42, no. 3, Dec. 2023, pp. 343+.

References

This project was funded (in whole or in part) by a grant awarded from the Sea Turtle Grants Program. The Sea Turtle Grants Program is funded from proceeds from the sale of the Florida Sea Turtle License Plate. Learn more at www.helpingseaturtles.org.

[i] Ch. 70-357, 1970 Fla. Laws 1137 (“An Act relating to the protection of marine turtles; amending section 370.12(1) to make certain acts with relation to sea turtles unlawful; providing for studies of green turtles and nesting preserves to be made by the department of natural resources; prohibiting importation or sale of products made from certain turtles; providing exceptions; providing an effective date”).

[ii] The behind-the-scenes story of the politics of establishing size limits for Green Turtles is recounted in Chapter 11 of Alison Reiser’s excellent book “The Case of the Green Turtle: An Uncensored History of a Conservation Icon.”

[iii] See e.g. Colin Limpus, Notes on growth rates of wild sea turtles, Marine Turtle Newsletter 10:3-5 (1979); Colin J. Limpus & David G. Walter, 1980. The growth of immature green turtles (Chelonia mydas) under natural conditions, 36(2) Herpetologica 162–165 (1980); George H. Balazs, Biology and Conservation of Sea Turtles 117–125 (K. A. Bjorndal ed., Smithsonian Institution Press 1995) (“Growth rates of immature green turtles in the Hawaiian Archipelago”).

[iv] Ch. 71-145, 1971 Fla. Laws 1031 (“An ACT relating to marine turtles amending §370.12(b), Florida Statutes, as amended by chapter 70-357, Laws of Florida; providing more specific regulations concerning the taking or possessing of green turtles; redefining the area in which the taking or possessing of other marine turtles is prohibited; deleting provisions for permits to capture turtles, providing penalties; providing an effective date”).

[v] Robert M. Ingle, Summary of Florida Commercial Marine Landings, 55–62 (Fla. Dep’t. of Nat. Res., Div. of Marine Res., Bureau of Marine Sci. & Tech. 1971) (“Florida’s sea turtle industry in relation to restrictions imposed in 1971”).

[vi] Willem Wijnstekers, The Evolution of CITES 31 (2011) (available at: https://cites.org/sites/default/files/common/resources/Evolution_of_CITES_9.pdf).

[vii] See Int’l Union for Conservation of Nature Background & History, https://www.iucnredlist.org/about/background-history.

[viii] Frederick Rowe, The Man Who Saved Sea Turtles: Archie Carr and the Origins of Conservation Biology 169–180 (2007).

[ix] Senate Memorial No. 795. 1973 Fla. Laws 1346 (“A Memorial to the United States Department of State seeking an international convention and agreement for the protection of the Green Sea Turtle”).

[x] Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966, Pub. L. No. 89-669, 80 Stat. 926 (available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-80/pdf/STATUTE-80-Pg926.pdf).

[xi] Endangered Species Conservation act of 1969, Pub. L. No. 91-135 83 Stat. 275 (available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-83/pdf/STATUTE-83-Pg275.pdf).

[xii] 35 F.R. 18319 (Dec. 2, 1970) (codified at 50 C.F.R. § 17.11).

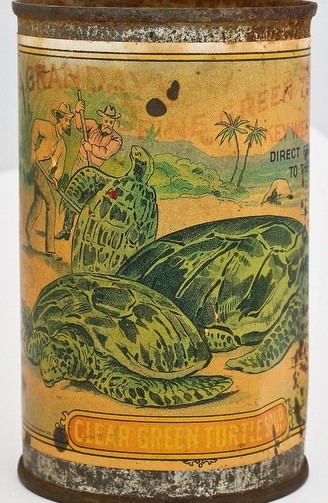

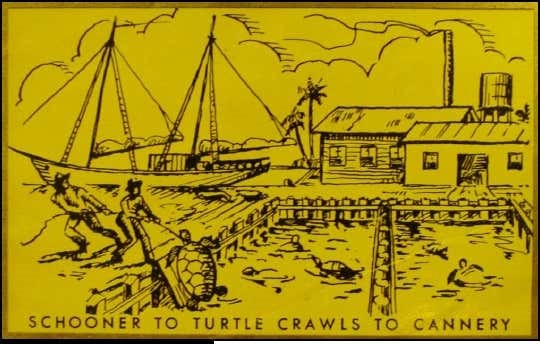

Photo credit: Mel Fisher Maritime Museum, Key West, Florida

Introduction

We ended our last blog describing the sobering report from the U.S. Fisheries Commissioner on the State of Florida Fisheries – which included sea turtles – in 1897. At a time when the State’s entire population was a little over one million, when land-based sources of pollution barely registered, and when seagrass meadows stretched unbroken across all the State’s estuaries, some fisheries already showed signs of stress. While the Commissioner reported declines in several fisheries, the most significant of these was the sea turtle, where reduced catch was reported across the state. The Commissioner stated in no uncertain terms: “The green turtle, one of the most valuable of the State’s fishery products, needs protection to prevent its extermination. The pernicious and destructive practice of gathering the eggs of this and the loggerhead should be prohibited.”[1] The Commissioner recommended a statewide ban on sea turtle harvest – on land and in the water – during the period when it seeks to the shore to lay its eggs.

Despite this stark assessment, the State continued to tinker with regulation of the turtle fishery for most of the rest of the 20th century, until the prescient Commissioner’s early warning bell nearly rang true. By the time the State took serious notice, sea turtles in Florida had effectively become commercially extinct, and were well on the way to biological extinction. In the second half of the century, scientists, led by Dr. Archie Carr, began to slowly unlock the mysteries of sea turtle biology and behavior to help to explain the rapid decline, and a small group of influential advocates organized to support his work and sea turtle conservation.

Early 20th Century Legislation: The Fisheries Issue

Photo credit: Mel Fisher Maritime Museum, Key West, Florida

In 1907, the Florida Legislature enacted statewide legislation banning green and loggerhead sea turtle harvest during the nesting season, but only while the turtles were on the beach, and no mention was made of egg collection.[2] In 1913, the first of what would eventually become a slew of local fishery laws that affected sea turtles was enacted in Dade County,[3] which had just begun its meteoric early century population growth trajectory. The law banned most net fishing in Biscayne Bay but created an exception for large mesh nets for continued sea turtle capture. The law also required non-citizens to apply for a county license to fish “for-hire,” a term that typically, refers to charter fishing, including for turtles. Commercial commodity fishing similarly required a license and applied to all persons in the County.

After a nearly three-decade hiatus in sea turtle legislative developments, a statewide bill was enacted in 1941 that essentially mirrored the 1907 statute. This law created a closed season for the harvest of all loggerhead and green turtles while “such turtle is out of the waters or upon the beaches of the state during the months of May, June, July and August of each year.”[4] It did not address nests or eggs. This statute moved Florida sea turtle law into the State’s new continuous revision system of statutory codification, which began in 1941.[5] The law governing sea turtles would for a period thereafter be found in Chapter 374, Florida Statutes, titled Saltwater Fisheries (until a subsequent reorganization placed it in Chapter 370, Florida Statutes). This law was reenacted in 1949 due to a post-war hiatus in the continuous revision process.[6] Section 374.16, as amended, essentially became the basis for what we now know as the Florida Marine Turtle Protection Act.

Photo credit: Mel Fisher Maritime Museum, Key West, Florida

Legislating Sea Turtle Conservation by “Whac-a-Mole”

In 1941, a local bill was enacted to protect sea turtles both in-water and on land in during the months of May, June, July, and August. The bill made it illegal to “take, destroy, mutilate, disturb, or interfere with any turtle egg or eggs, nest or nests, or any loggerhead or green turtle” during these months. The law applied to all “Counties in the Fourth Congressional District have a population greater than 39,000.”[7] At the time, this included Dade, Broward and Palm Beach Counties. In addition to including nest and eggs, which Section 374.16 had failed to do, this local bill prohibited harvest “…from the water adjacent to and touching the State of Florida” in the three counties to which it applied – perhaps the first time in-water harvest was prohibited in Florida.

The 1941 local South Florida bill began a trend in Florida fisheries law addressing sea turtles (as well as other species) where the legislature essentially engaged in a rear-guard game of “Whac-A-Mole,” addressing declines on beaches and in nearshore waters on a county-by-county basis. It also began a curious trend of sometimes legislating local bills, not by identifying counties by their name, but by their population. This may have been the result of concern over the constitutionality of certain geographically specific local bills.[8] Because population changes over time, the law could theoretically apply to other counties as their population changed, and hence it was not truly a constitutionally suspect “local bill.” However, this practice does not appear to have been uniform as it relates to sea turtle legislation.

In 1951, a law addressed sea turtles in Brevard County, an epicenter for Loggerhead nesting, for the first time.[9] The bill was nearly identical to the 1941 law that applied by population to Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach Counties, protecting sea turtles both in-water and on land during the May through August time span. However, it expanded the period during which nests and eggs were protected to include September and October, recognizing for the first time in law that these were significant nesting months as well.

In 1953, as part of a reorganization of the Florida Statutes, the chapter on Saltwater Fisheries, first adopted in 1941 as Chapter 374, became Chapter 370 – Salt Water Fisheries and Conservation (thus adding conservation to the chapter title). The legislature included a new Section 370.12, titled “Marine Animals; regulation” and made it unlawful to “take, possess, disturb, mutilate or in anywise destroy or cause to be destroyed and marine turtle nest or eggs at any time.”[10] This law differed from the general law that had carried forward from the original codification in 1941 and recodification in 1949 in one important way. It only addressed eggs and nests, seemingly leaving protection of turtles on nesting beaches or in-water to county-by-county local laws – a slew of which followed.

In 1955, legislatively mandated prohibitions on taking both sea turtles and/or their eggs during May through August were enacted for Martin County, with no distinction made for land or water. In that same year, local bills were also enacted (via the population-based method) that applied uniquely to Flagler, Brevard, St. Johns, and Sarasota Counties. The inclusion of Sarasota County marked the first time that west coast sea turtle populations were addressed. In 1957, Indian River County and St. Lucie County were similarly addressed.

1957 also marked significant developments in the general law addressing sea turtles statewide. Section 370.12 rectified the omission of sea turtles from the 1953 law prohibiting taking or tampering with their eggs and nests. The 1957 amendment added a Section 2 to the statute, and made it unlawful to “take, kill, possess, mutilate or in any way destroy any loggerhead or green turtle or other turtle while such turtle is on the beaches of Florida or within ½ mile seaward from the beaches during the months of May, June, July and August.”[11] In addition to adding this new spatially defined in-water protection, the statute expanded the protections to include other species. Thus, for the first time, Hawksbill, Leatherbacks and Atlantic ridley sea turtles were also protected.

As counties grew, the population-based method of legislating local fishery laws required new special laws for those counties that “grew out of” the existing local law. These new local laws sometimes reflected new developments in conservation, and sometimes seemed duplicative of the 1957 statewide statute – Section 370.12. In 1959, the Legislature prohibited the take, possession, and sale (or offer for sale) and transport of sea turtles or eggs during the May – August nesting season. This law applied to all species of sea turtles and their eggs and also prohibited sale, offer of sale and transport of sea turtles and their eggs, new restrictions in the evolving law. Identical language was used for local laws specific to Broward County, Palm Beach County, Martin County, Brevard County Volusia County, Duval County, Nassau County. That same year a special population-based local bill was enacted prohibiting spear fishing sea turtles, which applied only to Citrus County on Florida’s west coast. This marked the second time a Gulf Coast County came under specific regulation, and the first time spearing was prohibited anywhere.[12] In 1963, the second local law prohibiting spearfishing passed in the Upper Keys of Monroe County.[13]

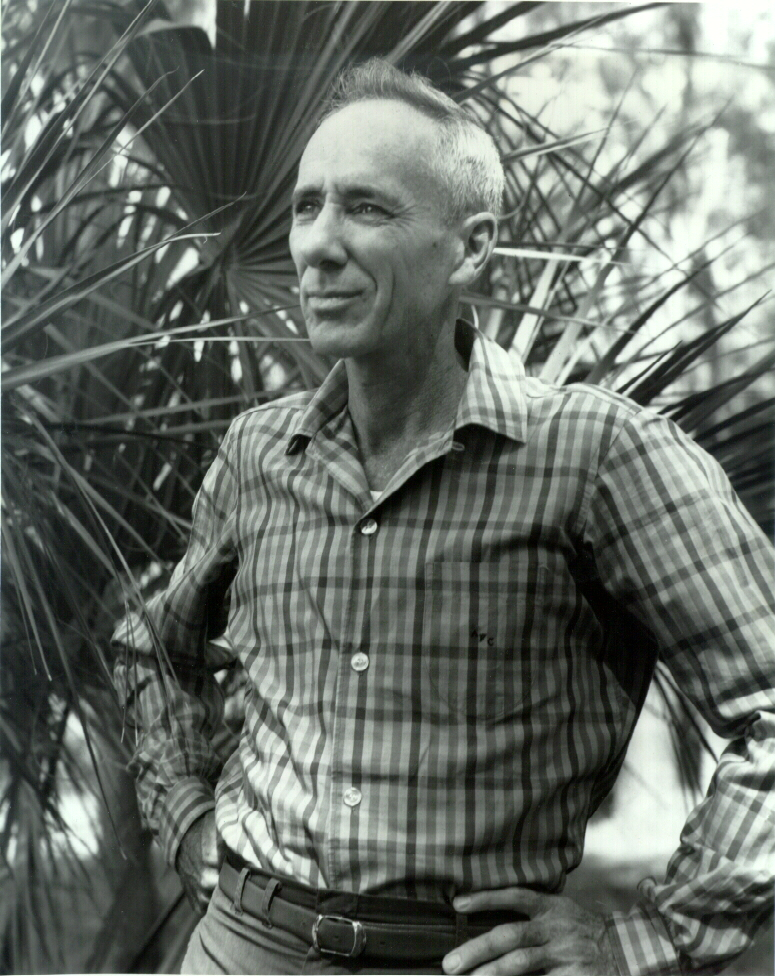

Dr. Archie Carr, founding Scientific Director of the Sea Turtle Conservancy.

The 1950s and The Rise of Modern Sea Turtle Science

As sea turtles continued their decline in Florida, and the state legislature continued to engage in its “Whac-A-Mole” approach to regulation of the fishery, a young zoologist at the University of Florida named Archie Carr began to narrow his research focus to sea turtles and slowly unpacked the mysterious life history of these enigmatic animals. Little was known of the once-ubiquitous species that frequented Florida waters and beaches to nest and forage. Over the course of the decade (and beyond), Carr laid the foundation for the science and policy that was to come. Beginning with an article titled “The Zoogeography and Migrations of Sea Turtles” in 1954,[14] Carr, colleagues and students published a series of articles that shed early light on sea turtle life history and behavior that would later be used to craft policy, including, migration, homing, sexual maturity, site fidelity, mating, predation, light sensitivity, and hatchling orientation among others. Titled the “Ecology and Migration of Sea Turtles,” and carried on by his students, the eight-part series spans a half a century. The first, published in 1956, focused on Florida, and on the population of juvenile non-breeding green turtles that supported the Cedar Key green turtle fishery.[15]

By the time Carr began his research on sea turtles, nesting green turtles had already all but disappeared from Florida’s beaches. The first confirmed reports of green turtle nesting in Florida in more than half a century were recorded in 1957 in Indian River County and in 1958 in Martin County.[16] In each case, only a single turtle was recorded. Nonetheless, these confirmed reports, and anecdotal evidence, led Carr to suspect that Florida’s Atlantic Coast had once been a significant rookery for green turtles.

While Carr is justly regarded as the foundational figure in Florida sea turtle science, others also played significant roles in the early efforts to understand the biology and behavior of sea turtles, and to manage the fishery. Robert Ingle, a towering figure in Florida fisheries management more broadly, played a significant role in the development of state sea turtle policy. Ingle was the first marine biologist hired by the State of Florida in 1949 and would go on to become Director of Research for the Florida State Board of Conservation Marine Laboratory [17], which would eventually become the highly respected Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute. A passionate advocate for conservation, and for fisheries management, Ingle cut his teeth on sea turtle research.[18] Later in his career, he had to grapple with the lack of understanding of the biology and behavior of sea turtles while attempting to maintain a fishery in decline largely due to that lack of understanding.

The 1950s and the Origin Story of Sea Turtle Advocacy

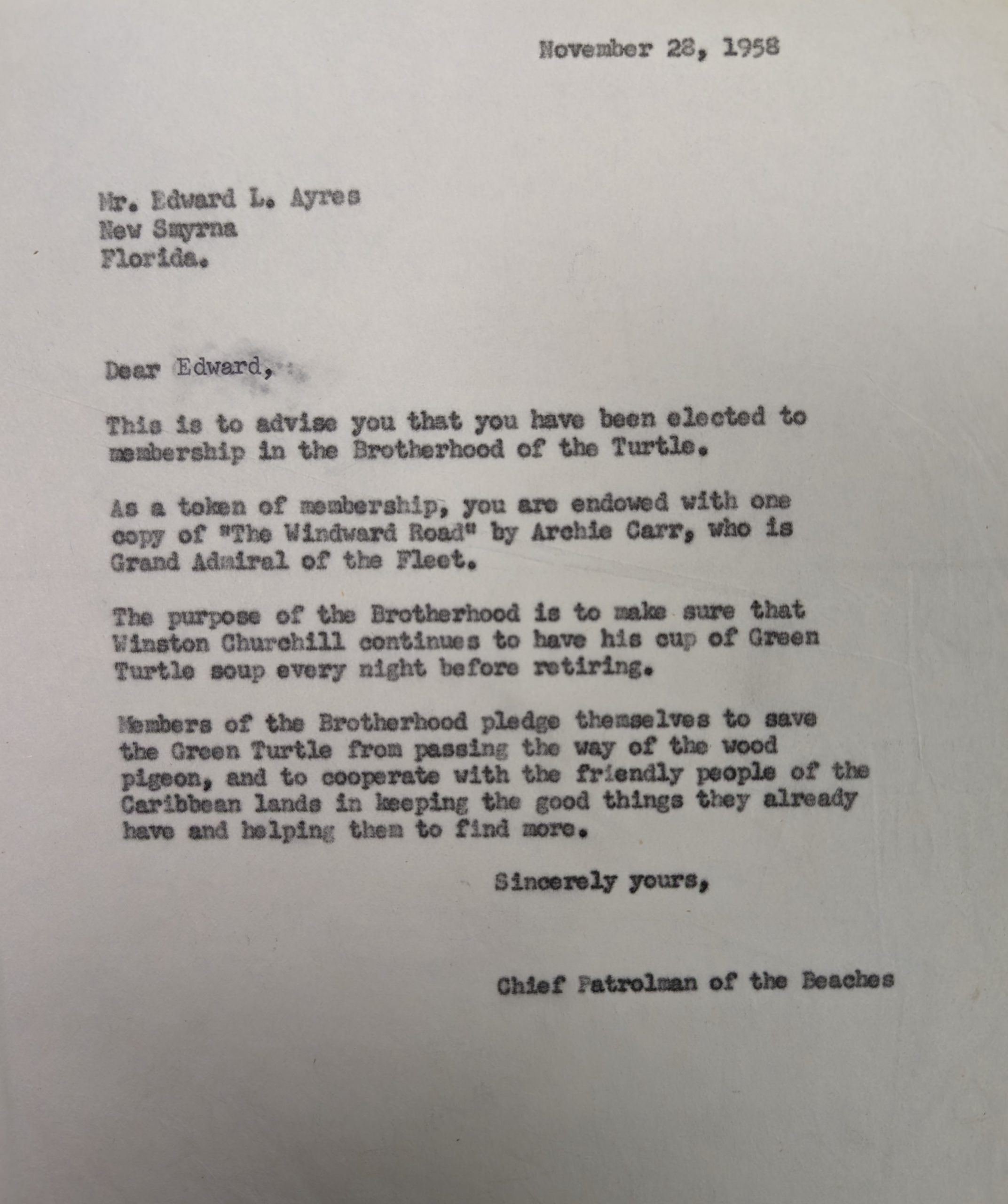

As researchers like Archie Carr continued to reveal the mysteries of sea turtle biology and behavior that made for such an unsustainable fishery, concern for the sea turtle’s well-being spilled over into the public. Carr’s award-winning book “The Windward Road,”[19] accessible to a broad audience, served as the catalyst for the storied and well-chronicled formation of the “Brotherhood of the Green Turtle,” in 1958. Smitten by Carr’s book, Joshua Powers formed the Brotherhood to create a well-heeled and well-positioned group to support Carr’s work and publicize the plight of sea turtles. Carr biographer, Frederick Rowe Davis, credits the organization for creating a space for sea turtle advocacy so Carr would be able to continue to pursue government funded research without being entangled in the politics of conservation.[20] The organization’s early advocacy work focused on international activity and contributed to protection of the nesting beach in Tortuguero, Costa Rica, the most prolific nesting beach in the Wider Caribbean, and the focus of Carr’s early research. Carr speculated that Tortuguero was the source of the green turtle diaspora throughout the Caribbean, including Florida. The Brotherhood of the Green Turtle would later become the Caribbean Conservation Corporation (CCC), and eventually the Sea Turtle Conservancy (STC), headquartered in Gainesville, Florida. CCC/STC would become a powerful force in the development of sea turtle policy in Florida, the United States and internationally.

A carbon copy of Joshua Power’s initial invitation to the Brotherhood of the Green Turtle. Photo credit: Sea Turtle Conservancy

Conclusion

The 20th century turned out to be an exercise in management futility as Florida sought to maintain a sea turtle fishery in the absence of sufficient understanding of sea turtle biology and behavior. County by county, the State adopted local law after local law attempting to restrict sea turtle and egg harvest where it was occurring, to no avail. Taking of turtles and eggs remained rampant. In the 1950s the plight of the turtle captured the attention of biologists who began to slowly unpack the science needed for management. It had become increasingly clear that sea turtles were wide-ranging, subject to depredation on foreign seas and shores, and matured slowly. At the same time, the world’s first non-governmental sea turtle advocacy organization, The Brotherhood of the Green Turtle, was established to support the work of Dr. Archie Carr, and to advocate for sea turtles throughout their range. By 1970, the tide began to turn – just in time.

Coming Next: “A Fishe No More”

Our final early history blog will explore the transition of sea turtle policy from one based in fisheries management to one based in protected species management. This transition did not occur in a vacuum. Across the globe the threat of species extinction loomed, and policymakers faced a growing chorus of environmental activism. Against this backdrop, Sea Turtles in Florida would soon become “A Fishe No More.”

Digging Deeper

Frederick R. Davis, The Man Who Saved Sea Turtles Archie Carr and the Origins of Conservation Biology (2007).

Archie F. Carr, The Windward Road Adventures of a Naturalist on Remote Caribbean Shores (1956).

Archie F. Carr, The Sea Turtle: So Excellente a Fishe (Univ. Presses of Fla., 2011).

Cory M. Malcom, The History and Archaeology of the Key West Turtle Fishing Industry, Mel Fisher Mar. Heritage Soc’y, (2013)

W.N. Witzell, The Origin, Evolution and Demise of the U.S. Sea Turtle Fisheries, 56(4) Marine Fisheries Rev. 8-23 (1994).

References

This project was funded (in whole or in part) by a grant awarded from the Sea Turtle Grants Program. The Sea Turtle Grants Program is funded from proceeds from the sale of the Florida Sea Turtle License Plate. Learn more at www.helpingseaturtles.org.

[1] John J. Brice, The Fish and fisheries of the coastal waters of Florida: Letter from the commissioner of fish and fisheries, transmitting in response to Senate resolution of February 15, 1895, a report of the fish and fisheries of the coastal waters of Florida, S. Doc. No. 54-100 (1897) (available at Biodiversity Heritage Library, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/4916).

[2] Act of 1907, ch. 5669, 1907 Fla. Laws 167 (“An ACT to Protect Logger Head and Green Turtles on the Coasts of the State of Florida”).

[3] Act of 1913, ch. 6574 – No. 74, 1913 Fla. Laws, 28 (“An ACT to Regulate the Catching of Fish and Turtle in Dade County Florida”).

[4] Fla. Stat. §374.16 (1941) (Closed season for loggerhead or green turtle while out of the water; Penalty.)

[5] See George A. Dietz, Sketch of the evolution of Florida law, 3(1) Fla. L. Rev., 74-82 (1950).

[6] Id. at 79. Also see Fla. Stat. §374.16 (1949) (Closed season for loggerhead or green turtle while out of the water; Penalty.)

[7] Act of 1941, ch. 20887-No. 679, 1941 Fla. Laws 2357—58 (“An ACT for the Protection of Loggerhead and Green Turtles and Eggs and Nests of Such Turtles in all Counties in the Fourth Congressional District of the State of Florida Having a Population of More than 39,000…”).

[8] Edward M. Jackson, Florida’s General Laws of Special or Local Application, 10(1) Fla. L. Rev. 90—97 (1957); Douglass D. Batchelor, Population Statutes Under the Florida Constitution, 1 U. Miami L. Rev. 97 (1947) (Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol1/iss2/5).

[9]. Act of 1953, Ch. 27415 – No. 936, 1953 Fla. Laws 299 (“An ACT for the Protection of Loggerhead and Green Turtles, and Eggs and Nests of Such Turtles, in Brevard County, Florida, and Providing a Penalty for the Violation of the Act”).

[10] Fla. Stat. §370.12 (1953).

[11]Act of 1957, ch. 57-771, 1957 Fla. Laws 1091 (An ACT relating to Saltwater Fisheries Conservation; prohibiting the taking, killing, possessing or mutilating of any sea turtle within a certain distance from the beaches of Florida during a certain period and providing penalties for violations) (codified at Fla. Stat. § 370.12 (1957)).

[12] Act of 1959, Ch.59-927, 1959 Fla. Laws 498—99 (An ACT relating to all counties having a population of not less than six thousand one hundred (6,100) nor more than six thousand three hundred (6,300) according to the latest official state-wide decennial census; prohibiting the gigging or spearing of green turtles; providing a penalty; providing an effective date).

[13] Act of 1963, ch. 63-1662, 1963 Laws of Florida 2328—29 (“An ACT relating to and prohibiting spearfishing in salt waters lying in and adjacent to certain areas of Monroe County providing for penalty; providing for a referendum providing an effective date”).

[14] Archie F. Carr, The Zoogeograpy and Migrations of Sea Turtles, Year Book of the Am. Phil. Soc’y, 138—40 (1954).

[15] Archie F. Carr & David K. Caldwell, The Ecology and Migrations of Sea Turtles, 1: Results of Field Work in Florida, 1955, Am. Museum Novitates; no. 1793. (1956).

[16] Archie F. Carr & Robert Ingle, The Green Turtle (Chelonia Mydas Mydas) in Florida, 9(3) Bull. of Marine Sci. of the Gulf and Caribbean 315-20. (1959).

[17] Stephen P. Geiger, In Memoriam Robert M. Ingle 1917–1997, 42(3) J. of Shellfish Rsch. 343—50 (2023).

[18] Robert M. Ingle & F. G. Walton Smith, Sea turtles and the turtle industry of the West Indies, Florida, and the Gulf of Mexico (1949).

[19] Archie F. Carr, The Windward Road Adventures of a Naturalist on Remote Caribbean Shores (1956).

[20] Frederick R. Davis, The Man Who Saved Sea Turtles Archie Carr and the Origins of Conservation Biology (2007).

A bill moving quickly through the Florida Legislature, SB 1126/HB 1641 – Regulation of Auxiliary Containers, would ban all local governments in Florida from regulating any kind of container that is used to transport merchandise, food, or beverages, including single-use plastic. The bill also proposes to cancel the update of the State’s retail bag study, which would analyze the need for new or different regulation of auxiliary containers, wrappings, or disposable plastic bags used by consumers to carry products from retail establishments.

The science is clear that plastic pollution is a major threat to sea turtles at every life stage. Microplastics are having an impact on sand incubation temperatures[1]; hatchlings are consuming it as soon as they leave the nest and make it to sea[2]; and adults are ingesting plastic at an alarming rate, leading to mortality.[3] The only way to effectively reduce this threat is to cut off plastic pollution at the source. Local governments across the State have witnessed this need and responded accordingly by limiting single-use plastic, foam, and more. This bill could make it even harder for Florida’s threatened and endangered sea turtles to recover.

In addition to protecting the marine environment, reducing plastic pollution makes economic sense. According to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, recreational activity along our coasts brings in hundreds of billions of dollars and supports hundreds of thousands of jobs each year.[4] Millions of people visit the State each year to enjoy our beaches, springs, lakes, and rivers; their patronage is dependent on the health of these iconic natural areas. By allowing plastic pollution to enter our environment without limits, the value of our natural resources to visitors will be greatly diminished.

Finally, the passage of this bill could prevent Floridians from avoiding harmful single-use plastic. Scientists have learned that microplastics are in their air that we breathe[5], the food we consume[6], the water we drink[7], and they have even been found in breastmilk[8]. Local government limits on single-use plastic allow for businesses to rethink the packaging materials they use to transport goods, which is beneficial to human health.

Action needed now: HB 1641 will be heard in the FL House State Affairs Committee on February 14 at 9 a.m. We ask that you email or call committee members and urge them to vote NO on HB 1641. Their contact information can be found here:

Chair McClure: lawrence.mcclure@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5068

Vice Chair Caruso: mike.caruso@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5087

Representative Alvarez: danny.alvarez@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5069

Representative Rayner: michele.rayner@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5062

Representative Bartleman: robin.bartleman@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5103

Representative Black: dean.black@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5015

Representative Buchanan: james.buchanan@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5074

Representative Busatta Cabrera: demi.busattacabrera@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5114

Representative Casello: joe.casello@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5090

Representative Eskamani: anna.eskamani@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5042

Representative Fabricio: tom.fabricio@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5110

Representative Gantt: ashley.gantt@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5109

Representative Griffitts, Jr,: Griff.Griffitts@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5006

Representative Holcomb: jeff.holcomb@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5053

Representative Mooney: jim.mooney@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5120

Representative Persons-Mulicka: jenna.persons@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5078

Representative Porras: JuanCarlos.Porras@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5119

Representative Roach: spencer.roach@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5076

Representative Robinson: Felicia.robinson@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5104

Representative Roth: rick.roth@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5094

Representative Temple: john.temple@myfloridahouse.gov, (850) 717-5052

[1] FSU Researchers: Hotter Sand from Microplastics Could Affect Sea Turtle Development

[2] Plastic Ingestion in Post-hatchling Sea Turtles: Assessing a Major Threat in Florida Near Shore Waters

[3] A quantitative analysis linking sea turtle mortality and plastic debris ingestion

[4] Investing in Florida’s Coastal & Oceans Futures – FDEP

[5] How microplastics are transported and deposited in realistic upper airways

[6] It’s Not Just Seafood: New Study Finds Microplastics in Nearly 90% of Proteins Sampled, Including Plant-Based Meat Alternatives

[7] Why you may be eating and drinking more microplastics than you thought

[8] Microplastics found in human breast milk for the first time

New York Public Library Digital Collections, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-52a8-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 (accessed 6 June 2020).

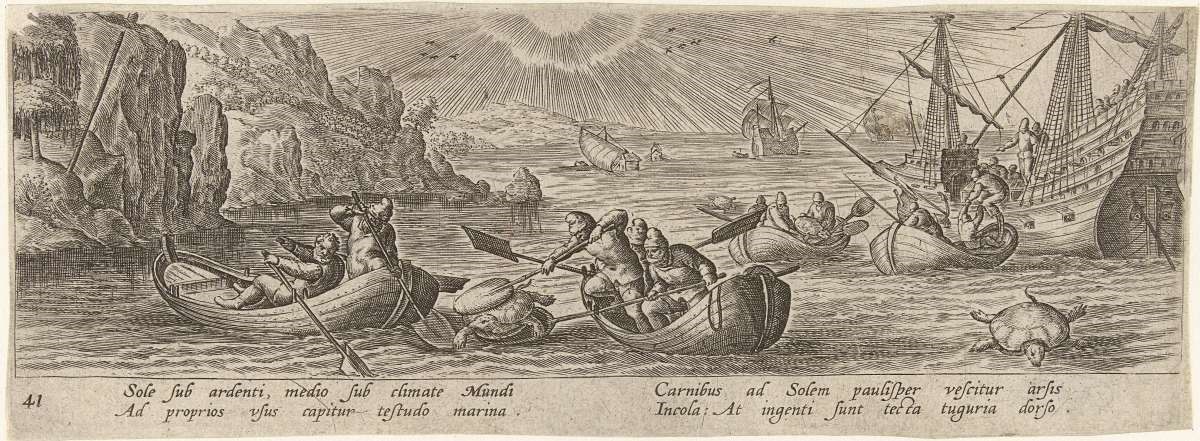

Long before sea turtles were revered as charismatic megafauna worthy of protection in their own right, they were a valuable source of protein that could be counted on by both indigenous cultures and early colonial maritime powers.[1] In 1513, Ponce de Leon reputedly reprovisioned with more than one hundred sea turtles for his return to Spain at a tiny archipelago south of Key West.[2] He would name them “Las Tortugas”(The Turtle Islands), and they would become a part of Spanish Florida. As the colonial powers overwhelmed tropical regions, decimating indigenous populations, sea turtles quickly grew in importance as a commodity for both local and transatlantic trade. This led to the gradual development of a fisheries-based approach to sea turtle conservation.

The regulation of sea turtles in western culture dates to at least 1620 when the British colonial government of Bermuda bemoaned the wanton destruction of the Green Turtles that found their way north to the tiny British island protectorate, attracted by lush sea grass beds and near tropical waters the Gulf Stream. The Old English text from a 1620 Bermudian law, titled “AN ACT AGYNST THE KILLINGE OF OUER YOUNG TORTOYSES,” provided both the title and the forward to Archie Carr’s collection of natural history essays titled “So Excellente a Fishe.”[3] Management of sea turtles as a fishery would serve as the basis for sea turtle “conservation” for the next 350 years, until global depletion of sea turtle populations rendered them commercially extinct, and the global species protection movement of the early 1970s rescued them from biological extinction. While it is beyond the scope of this project to trace the colonial lineage of sea turtle exploitation, suffice it to say trade in sea turtles quickly followed the westward expansion of the great colonial powers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[4]

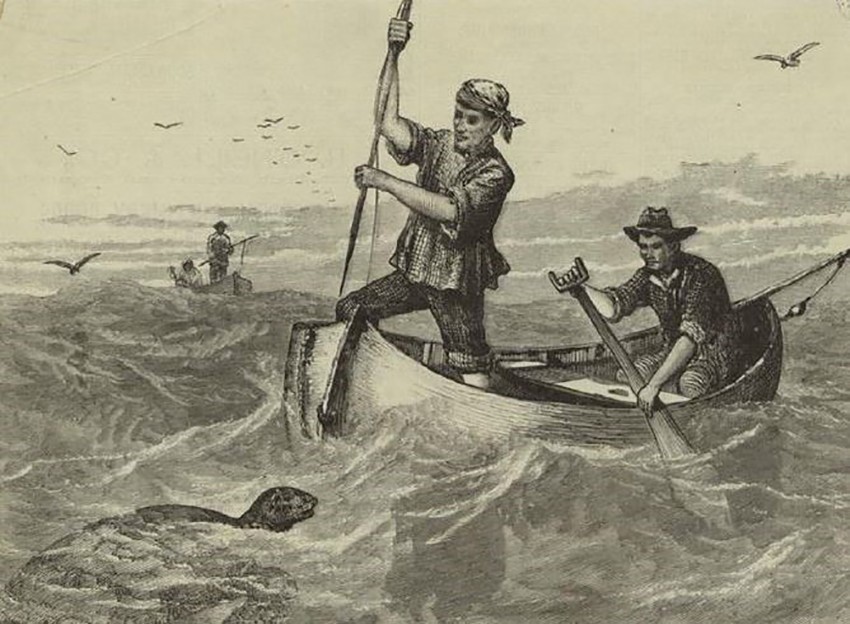

Hunt on sea turtles. Philips Galle (attributed to..), after Hans Bol, 1582-1633, engraving, 215 x 81 mm. (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-6647

Efforts to regulate trade in sea turtles in Florida predate statehood. As the newly independent United States of America added Florida as a territory in 1821, a variety of maritime conflicts arose with its close neighbor, the British colony of the Bahamas. During Spanish rule, Bahamian fishermen had been accustomed to fishing in Florida waters, and hunting turtles and their eggs on Florida beaches. As conflict between the new U.S. Territory and the neighboring crown colony mounted, the Governor of the Bahamas reached out to the U.S. State Department to negotiate a treaty with the United States to allow Bahamian fishermen to continue taking turtles from U.S. and Florida waters and beaches.[5] Florida’s territorial governor implored the U.S. to ignore this request and protect what he regarded as a valuable economic asset to the Territory, and within the authority of the Territory to regulate for its own interests.[6]

At the same time, the Territorial government enacted Florida’s first sea turtle management law – “An Act for the Protection of the Fisheries on the Coasts of Florida, and to Raise Revenue Therefrom.”[7] The law required foreign vessels to register in Florida, and to land their catch – including sea turtles – in Florida. These requirements greatly diminished Bahamian interest in fishing in Territorial waters. The Territorial Governor was authorized to name one or more “fish commissioners” to implement the law. Interestingly, the law also forbade fishermen from employing, trading, or taking on board Seminole Indians, some of whom had just concluded the Treaty to end the First Seminole Indian War. Penalties for violating the Fisheries Act included fines and vessel forfeiture. Over the ensuing years, many Bahamian turtle fishers took residence in Florida to continue to fish the State’s waters.[8] Even so, entreaties for fishery access from the Bahamian government to the U.S. government continued (albeit without success), as the issue of fishing and turtles grew increasingly enmeshed in concerns over slavery (prohibited in the Bahamas), aid and comfort to the Seminoles (the Seminole Indian Wars raged in this period), and illegal competition for “wrecking” rights (salvage).[9]

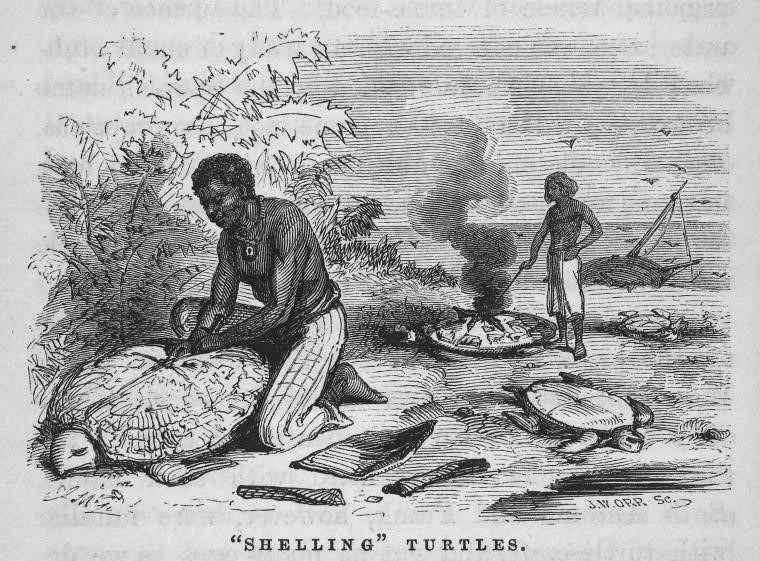

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. “Shelling” Turtles.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1855. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-7395-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

When Florida became a state in 1845, it re-adopted many of its territorial laws to reflect the new sovereign state’s administrative and judicial framework, including the 1832 Territorial Fisheries Act. [10] Provisions of the law that addressed the Seminoles were tightened to preclude any interactions with the Tribe by fishers.

In 1860, all prior fisheries laws were repealed, and a new law was enacted.[11] Provisions regarding the Seminoles were dropped as the issue’s immediacy faded. A new provision in the 1860 law clarified the State’s maritime jurisdiction and prohibited out of state vessels from taking fish or turtles in waters within “one marine league” (three nautical miles) of the coast, which at the time was also considered the limits of the U.S. Territorial Sea (it is now 12 miles).

Additionally, the 1860 fisheries law specifically prohibited any person, citizen, or non-resident, from “catching fish for the roes only, or turtles for the eggs only, or in any manner wantonly destroying the fish or turtle on the coast of this State.” Under this statute, even resident Floridians were prohibited from engaging in these activities, perhaps reflecting concerns over the biological significance of gravid adults to the population at large. Throughout this period, until the turn of the century, the State of Florida continued a turtle fishery policy premised largely on vessel licensing. In 1874, the State imposed a licensing requirement on all vessels fishing for turtle, oysters, and sponges, with escalating fees by weight beginning with boats greater than 10 tons.[12] By the turn of the century, pressure on turtle and other fisheries began to manifest in diminished harvests, catching the attention of federal fisheries managers. The State’s population at the time was scarcely half of million.

‘Central America: Spearing Green Turtle on the Musquito [I.E. Mosquito] Coast’.

Source: New York Public Library Digital Collections, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-08f7-a3d9-e040 (accessed 6 June 2020).

A remarkable 1897 congressionally mandated report on the fisheries of Florida sounded the first alarm on overfishing of sea turtles (and other species) in the state and presaged the passage of what was likely the first law to protect nesting sea turtles in the state in 1907. The report, titled “The Fish and Fisheries of the Coastal Waters of the State of Florida” and written by United States Commissioner of Fisheries J.J. Brice, surveyed the status of the State’s fisheries, including the turtle fishery.[13] The report suggests a rudimentary but growing knowledge of sea turtle nesting behavior – discounting one theory that female turtles return to the beach to escort their hatchlings back to the sea.

Referring to the Green Turtle, the report states: “Overfishing and the destruction of its eggs have greatly reduced its abundance in this State, and the annual catch is now much less than formerly.”

Beyond the reduction in numbers of turtles, the report also highlights a drop in average weight of landed turtles, noting that in some parts of the state “where fishing has been excessive… it is under 50 pounds.” The report identifies the major centers of turtle fishing at the time, including: the Indian River Lagoon area, Biscayne Bay, Key West and the Lower Keys, Tampa Bay, and the Cedar Keys, noting its decline in each and their effective demise in Tampa Bay.

The report concludes: “The Green Turtle, one of the State’s most valuable fishery products, needs protection to prevent its extermination.” The report recommended a moratorium on taking turtles during the nesting season, creating a minimum weight limit to protect juvenile turtles, and a prohibition on “the pernicious and destructive practice of gathering the eggs of [Green] and loggerhead turtles.” Despite this dire warning, both the harvest and the resulting population decline continued. At the time, the state was home to only 500,000 people. Clearly, there was something about the nature of the sea turtle’s biology which did not lend itself to continuing harvest.

In 1907, the Florida legislature acted on part of one of the Report’s conclusions and passed a statute prohibiting taking, killing, mutilating or “in any wise destroying any logger head [sic] or green turtle while any such turtle is laying or found out of the waters or upon the beaches of the State of Florida during the months of May, June, July and August of any year.”[14] The 1897 U.S. Fish Commissioner’s Report had not distinguished land from water in its recommendation, but the state legislature chose only to limit harvest on land. Despite its impact on the turtle population, in-water turtle fishing during the nesting season would continue well into the 20th century, much to the chagrin of prominent sea turtle biologists such as Archie Carr.

In our next blog post, we will track the sporadic development of geographically localized sea turtle legislation in the early to mid-20th century, as legislators sought to satisfy the needs of the fishery, while attempting to address continuing declines in sea turtles in Florida. We will then turn to the growing movement to protect sea turtles in Florida and globally, as calls to protect imperiled species more generally gained momentum and scientists gained a deeper understanding of sea turtle biology.

Readers interested in digging deeper into the literature on sea turtle during the Age of Exploration, the Colonial Era and early Florida history can find more in several excellent publications.

Alison Rieser. The Case of the Green Turtle: An Uncensored History of a Conservation Icon, 2012.

James Parsons. The Green Turtle and Man. (Gainesville, University of Florida Press, 1962.

Archie Carr. Handbook of Turtles: The Turtles of the United States, Canada, and Baja California. Cornell University Press, 1995.

Robert M. Ingle. Sea Turtles and the Turtle Industry of the West Indies, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico, University of Miami Press, 1974.

Karl Offen. “Subsidy from Nature: Green Sea Turtles in the Colonial Caribbean.” Journal of Latin American Geography, vol. 19, no. 1, Jan. 2020.

[1] See generally Karl Offen, Subsidy from Nature: Green Sea Turtles in the Colonial Caribbean, 19 J. of Latin Am. Geography, Jan. 2020, at 182, https://doi.org/10.1353/lag.2020.0025; Lynn B. Harris, Maritime Cultural Encounters and Consumerism of Turtles and Manatees: An Environmental History of the Caribbean, 32 Int’l J. of Mar. Hist., November 2020, at 789, https://doi.org/10.1177/0843871420973669.

[2] Donna J. Souza, The Persistence of Sail in the Age of Steam (1998)(Chapter 9, The Dry Tortugas). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0139-2_2. The Tortugas would later become the Dry Tortugas to remind sailors there was no freshwater on the islands.

[3] Archie Carr, So Excellent a Fishe: The Natural History of the Sea Turtle (2011).

[4] For a depiction of the sea turtles in the age of exploration through an artistic lens, see Erma Hermens, Crossing and Turning: the Sea Turtle Trade in the 17th Century, Looking Through Art Blog (June 3, 2020), https://lookingthroughartblog.wordpress.com/2020/06/03/crossing-and-turning-the-sea-turtle-trade-in-the-17th-century/.

[5] The Territorial Papers of the United States (The Territory of Florida, 1828-1834), 24 The Nat’l Archives, 557 (1959).

[6] Report of James D. Westcott, Jr., Secretary & Acting Governor to Territorial Legislative Council Journal of the Proceedings of the Legislative Council, 10th Sess., at 5, (Jan. 2, 1832).

[7] An Act for the Protection of the Fisheries on the Coasts of Florida, and to raise revenue therefrom, 57 Acts of the Legislative Council of the Territory of Florida, at 82 (1832).

[8] Alison Reiser, The Case of the Green Turtle: An Uncensored History of a Conservation Icon 21-22 (2012).

[9] 32d Cong., 2d. Sess. Executive Documents of the United States, (1852-53).

[10] An Act for the Protection of the Fisheries on the Coast of Florida, ch. 34,1845 Fla. Laws 67.

[11] An Act to Regulate Fishing on the Coast of the State of Florida, ch. 1,121, 1860 Fla. Laws 67.

[12] An Act for the Assessment and Collection of Revenue, ch. 1976, 1874 Fla. Laws 13.

[13] John Jones Brice, The Fish and fisheries of the coastal waters of Florida: Letter from the commissioner of fish and fisheries, transmitting in response to Senate resolution of February 15, 1895, a report of the fish and fisheries of the coastal waters of Florida, S. Doc. No. 54-100 (1897) (via Biodiversity Heritage Library, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/4916 )

[14] An Act to Protect Logger Head and Green Turtles on the Coasts of the State of Florida, ch. 5669, 1907 Fla. Laws 167.

This project was funded (in whole or in part) by a grant awarded from the Sea Turtle Grants Program. The Sea Turtle Grants Program is funded from proceeds from the sale of the Florida Sea Turtle License Plate. Learn more at www.helpingseaturtles.org.

Dating back to its territorial past, Florida has played a major role in the global development of sea turtle protection policy – and the science that supports it. Over the next year STC will tell this story through an interactive ArcGIS StoryMap, which will contain a curated timeline, a series of articles (in blog format), and accompanying social media posts, all based on original research, including oral history interviews. The project will be led by University of Florida Law Professor Emeritus Thomas T. Ankersen and Sea Turtle Conservancy (STC) Development and Policy Coordinator Stacey Gallagher.