Sea Turtle Conservation in Florida: Part II

Not For Long a Fishe:

The Early History of Sea Turtle Conservation Law and Policy in Florida, Part II

Thomas T. Ankersen, Professor Emeritus

University of Florida Levin College of Law

Introduction

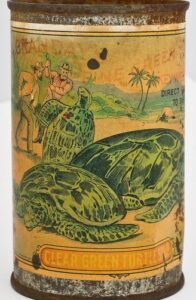

We ended our last blog describing the sobering report from the U.S. Fisheries Commissioner on the State of Florida Fisheries – which included sea turtles – in 1897. At a time when the State’s entire population was a little over one million, when land-based sources of pollution barely registered, and when seagrass meadows stretched unbroken across all the State’s estuaries, some fisheries already showed signs of stress. While the Commissioner reported declines in several fisheries, the most significant of these was the sea turtle, where reduced catch was reported across the state. The Commissioner stated in no uncertain terms: “The green turtle, one of the most valuable of the State’s fishery products, needs protection to prevent its extermination. The pernicious and destructive practice of gathering the eggs of this and the loggerhead should be prohibited.”[1] The Commissioner recommended a statewide ban on sea turtle harvest – on land and in the water – during the period when it seeks to the shore to lay its eggs.

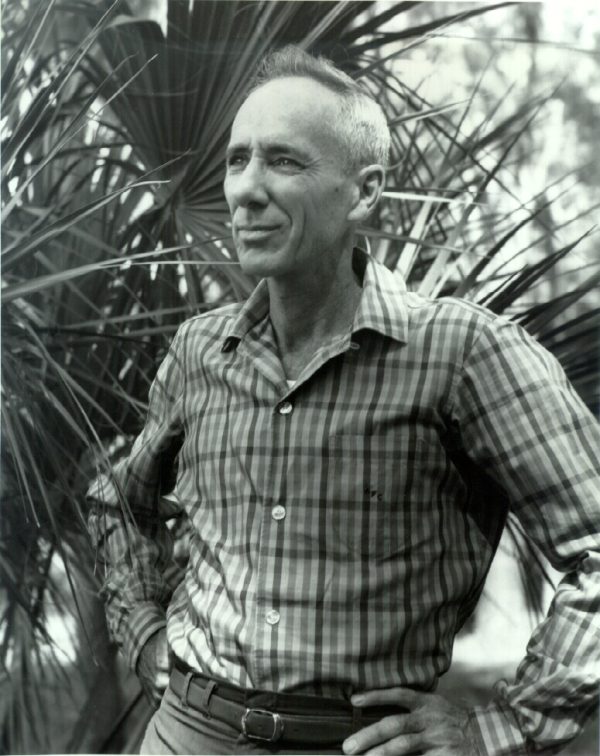

Despite this stark assessment, the State continued to tinker with regulation of the turtle fishery for most of the rest of the 20th century, until the prescient Commissioner’s early warning bell nearly rang true. By the time the State took serious notice, sea turtles in Florida had effectively become commercially extinct, and were well on the way to biological extinction. In the second half of the century, scientists, led by Dr. Archie Carr, began to slowly unlock the mysteries of sea turtle biology and behavior to help to explain the rapid decline, and a small group of influential advocates organized to support his work and sea turtle conservation.

Early 20th Century Legislation: The Fisheries Issue

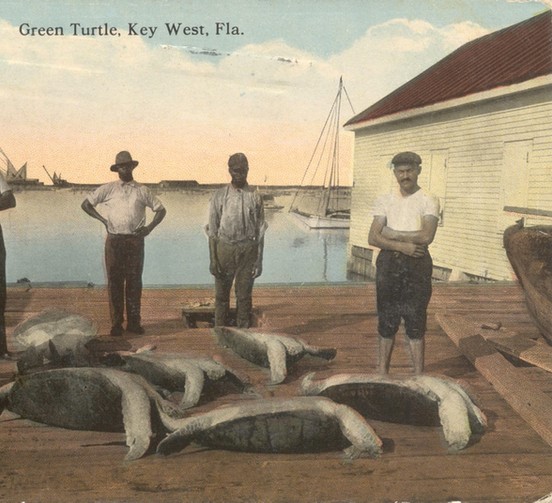

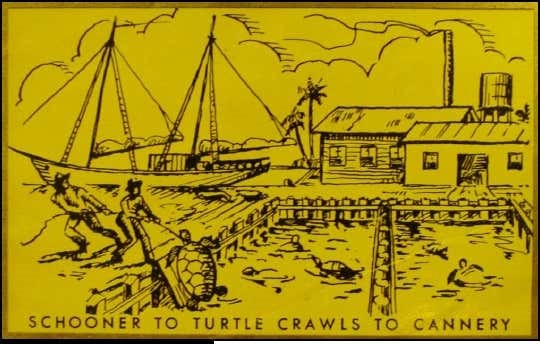

Photo credit: Mel Fisher Maritime Museum, Key West, Florida

In 1907, the Florida Legislature enacted statewide legislation banning green and loggerhead sea turtle harvest during the nesting season, but only while the turtles were on the beach, and no mention was made of egg collection.[2] In 1913, the first of what would eventually become a slew of local fishery laws that affected sea turtles was enacted in Dade County,[3] which had just begun its meteoric early century population growth trajectory. The law banned most net fishing in Biscayne Bay but created an exception for large mesh nets for continued sea turtle capture. The law also required non-citizens to apply for a county license to fish “for-hire,” a term that typically, refers to charter fishing, including for turtles. Commercial commodity fishing similarly required a license and applied to all persons in the County.

After a nearly three-decade hiatus in sea turtle legislative developments, a statewide bill was enacted in 1941 that essentially mirrored the 1907 statute. This law created a closed season for the harvest of all loggerhead and green turtles while “such turtle is out of the waters or upon the beaches of the state during the months of May, June, July and August of each year.”[4] It did not address nests or eggs. This statute moved Florida sea turtle law into the State’s new continuous revision system of statutory codification, which began in 1941.[5] The law governing sea turtles would for a period thereafter be found in Chapter 374, Florida Statutes, titled Saltwater Fisheries (until a subsequent reorganization placed it in Chapter 370, Florida Statutes). This law was reenacted in 1949 due to a post-war hiatus in the continuous revision process.[6] Section 374.16, as amended, essentially became the basis for what we now know as the Florida Marine Turtle Protection Act.

Legislating Sea Turtle Conservation by “Whac-a-Mole”

In 1941, a local bill was enacted to protect sea turtles both in-water and on land in during the months of May, June, July, and August. The bill made it illegal to “take, destroy, mutilate, disturb, or interfere with any turtle egg or eggs, nest or nests, or any loggerhead or green turtle” during these months. The law applied to all “Counties in the Fourth Congressional District have a population greater than 39,000.”[7] At the time, this included Dade, Broward and Palm Beach Counties. In addition to including nest and eggs, which Section 374.16 had failed to do, this local bill prohibited harvest “…from the water adjacent to and touching the State of Florida” in the three counties to which it applied – perhaps the first time in-water harvest was prohibited in Florida.

The 1941 local South Florida bill began a trend in Florida fisheries law addressing sea turtles (as well as other species) where the legislature essentially engaged in a rear-guard game of “Whac-A-Mole,” addressing declines on beaches and in nearshore waters on a county-by-county basis. It also began a curious trend of sometimes legislating local bills, not by identifying counties by their name, but by their population. This may have been the result of concern over the constitutionality of certain geographically specific local bills.[8] Because population changes over time, the law could theoretically apply to other counties as their population changed, and hence it was not truly a constitutionally suspect “local bill.” However, this practice does not appear to have been uniform as it relates to sea turtle legislation.

In 1951, a law addressed sea turtles in Brevard County, an epicenter for Loggerhead nesting, for the first time.[9] The bill was nearly identical to the 1941 law that applied by population to Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach Counties, protecting sea turtles both in-water and on land during the May through August time span. However, it expanded the period during which nests and eggs were protected to include September and October, recognizing for the first time in law that these were significant nesting months as well.

In 1953, as part of a reorganization of the Florida Statutes, the chapter on Saltwater Fisheries, first adopted in 1941 as Chapter 374, became Chapter 370 – Salt Water Fisheries and Conservation (thus adding conservation to the chapter title). The legislature included a new Section 370.12, titled “Marine Animals; regulation” and made it unlawful to “take, possess, disturb, mutilate or in anywise destroy or cause to be destroyed and marine turtle nest or eggs at any time.”[10] This law differed from the general law that had carried forward from the original codification in 1941 and recodification in 1949 in one important way. It only addressed eggs and nests, seemingly leaving protection of turtles on nesting beaches or in-water to county-by-county local laws – a slew of which followed.

In 1955, legislatively mandated prohibitions on taking both sea turtles and/or their eggs during May through August were enacted for Martin County, with no distinction made for land or water. In that same year, local bills were also enacted (via the population-based method) that applied uniquely to Flagler, Brevard, St. Johns, and Sarasota Counties. The inclusion of Sarasota County marked the first time that west coast sea turtle populations were addressed. In 1957, Indian River County and St. Lucie County were similarly addressed.

1957 also marked significant developments in the general law addressing sea turtles statewide. Section 370.12 rectified the omission of sea turtles from the 1953 law prohibiting taking or tampering with their eggs and nests. The 1957 amendment added a Section 2 to the statute, and made it unlawful to “take, kill, possess, mutilate or in any way destroy any loggerhead or green turtle or other turtle while such turtle is on the beaches of Florida or within ½ mile seaward from the beaches during the months of May, June, July and August.”[11] In addition to adding this new spatially defined in-water protection, the statute expanded the protections to include other species. Thus, for the first time, Hawksbill, Leatherbacks and Atlantic ridley sea turtles were also protected.

As counties grew, the population-based method of legislating local fishery laws required new special laws for those counties that “grew out of” the existing local law. These new local laws sometimes reflected new developments in conservation, and sometimes seemed duplicative of the 1957 statewide statute – Section 370.12. In 1959, the Legislature prohibited the take, possession, and sale (or offer for sale) and transport of sea turtles or eggs during the May – August nesting season. This law applied to all species of sea turtles and their eggs and also prohibited sale, offer of sale and transport of sea turtles and their eggs, new restrictions in the evolving law. Identical language was used for local laws specific to Broward County, Palm Beach County, Martin County, Brevard County Volusia County, Duval County, Nassau County. That same year a special population-based local bill was enacted prohibiting spear fishing sea turtles, which applied only to Citrus County on Florida’s west coast. This marked the second time a Gulf Coast County came under specific regulation, and the first time spearing was prohibited anywhere.[12] In 1963, the second local law prohibiting spearfishing passed in the Upper Keys of Monroe County.[13]

The 1950s and The Rise of Modern Sea Turtle Science

As sea turtles continued their decline in Florida, and the state legislature continued to engage in its “Whac-A-Mole” approach to regulation of the fishery, a young zoologist at the University of Florida named Archie Carr began to narrow his research focus to sea turtles and slowly unpacked the mysterious life history of these enigmatic animals. Little was known of the once-ubiquitous species that frequented Florida waters and beaches to nest and forage. Over the course of the decade (and beyond), Carr laid the foundation for the science and policy that was to come. Beginning with an article titled “The Zoogeography and Migrations of Sea Turtles” in 1954,[14] Carr, colleagues and students published a series of articles that shed early light on sea turtle life history and behavior that would later be used to craft policy, including, migration, homing, sexual maturity, site fidelity, mating, predation, light sensitivity, and hatchling orientation among others. Titled the “Ecology and Migration of Sea Turtles,” and carried on by his students, the eight-part series spans a half a century. The first, published in 1956, focused on Florida, and on the population of juvenile non-breeding green turtles that supported the Cedar Key green turtle fishery.[15]

By the time Carr began his research on sea turtles, nesting green turtles had already all but disappeared from Florida’s beaches. The first confirmed reports of green turtle nesting in Florida in more than half a century were recorded in 1957 in Indian River County and in 1958 in Martin County.[16] In each case, only a single turtle was recorded. Nonetheless, these confirmed reports, and anecdotal evidence, led Carr to suspect that Florida’s Atlantic Coast had once been a significant rookery for green turtles.

While Carr is justly regarded as the foundational figure in Florida sea turtle science, others also played significant roles in the early efforts to understand the biology and behavior of sea turtles, and to manage the fishery. Robert Ingle, a towering figure in Florida fisheries management more broadly, played a significant role in the development of state sea turtle policy. Ingle was the first marine biologist hired by the State of Florida in 1949 and would go on to become Director of Research for the Florida State Board of Conservation Marine Laboratory [17], which would eventually become the highly respected Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute. A passionate advocate for conservation, and for fisheries management, Ingle cut his teeth on sea turtle research.[18] Later in his career, he had to grapple with the lack of understanding of the biology and behavior of sea turtles while attempting to maintain a fishery in decline largely due to that lack of understanding.

The 1950s and the Origin Story of Sea Turtle Advocacy

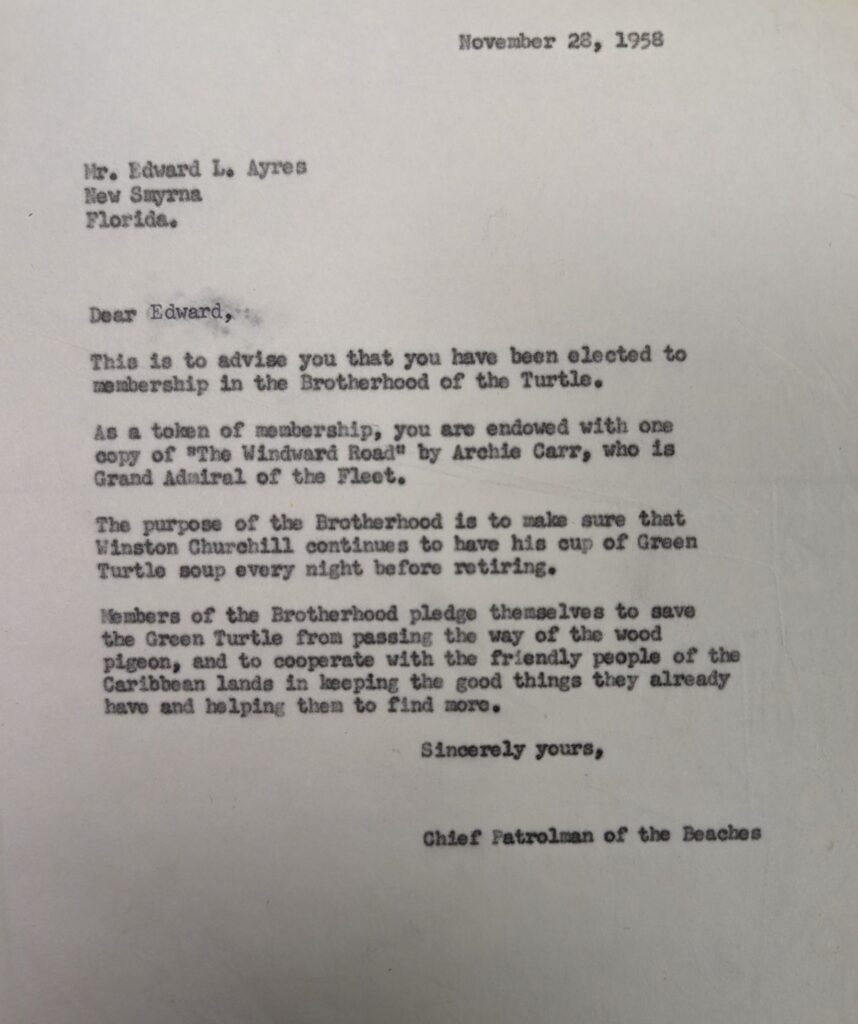

As researchers like Archie Carr continued to reveal the mysteries of sea turtle biology and behavior that made for such an unsustainable fishery, concern for the sea turtle’s well-being spilled over into the public. Carr’s award-winning book “The Windward Road,”[19] accessible to a broad audience, served as the catalyst for the storied and well-chronicled formation of the “Brotherhood of the Green Turtle,” in 1958. Smitten by Carr’s book, Joshua Powers formed the Brotherhood to create a well-heeled and well-positioned group to support Carr’s work and publicize the plight of sea turtles. Carr biographer, Frederick Rowe Davis, credits the organization for creating a space for sea turtle advocacy so Carr would be able to continue to pursue government funded research without being entangled in the politics of conservation.[20] The organization’s early advocacy work focused on international activity and contributed to protection of the nesting beach in Tortuguero, Costa Rica, the most prolific nesting beach in the Wider Caribbean, and the focus of Carr’s early research. Carr speculated that Tortuguero was the source of the green turtle diaspora throughout the Caribbean, including Florida. The Brotherhood of the Green Turtle would later become the Caribbean Conservation Corporation (CCC), and eventually the Sea Turtle Conservancy (STC), headquartered in Gainesville, Florida. CCC/STC would become a powerful force in the development of sea turtle policy in Florida, the United States and internationally.

Conclusion

The 20th century turned out to be an exercise in management futility as Florida sought to maintain a sea turtle fishery in the absence of sufficient understanding of sea turtle biology and behavior. County by county, the State adopted local law after local law attempting to restrict sea turtle and egg harvest where it was occurring, to no avail. Taking of turtles and eggs remained rampant. In the 1950s the plight of the turtle captured the attention of biologists who began to slowly unpack the science needed for management. It had become increasingly clear that sea turtles were wide-ranging, subject to depredation on foreign seas and shores, and matured slowly. At the same time, the world’s first non-governmental sea turtle advocacy organization, The Brotherhood of the Green Turtle, was established to support the work of Dr. Archie Carr, and to advocate for sea turtles throughout their range. By 1970, the tide began to turn – just in time.

Coming Next: “A Fishe No More”

Our final early history blog will explore the transition of sea turtle policy from one based in fisheries management to one based in protected species management. This transition did not occur in a vacuum. Across the globe the threat of species extinction loomed, and policymakers faced a growing chorus of environmental activism. Against this backdrop, Sea Turtles in Florida would soon become “A Fishe No More.”

Digging Deeper

Frederick R. Davis, The Man Who Saved Sea Turtles Archie Carr and the Origins of Conservation Biology (2007).

Archie F. Carr, The Windward Road Adventures of a Naturalist on Remote Caribbean Shores (1956).

Archie F. Carr, The Sea Turtle: So Excellente a Fishe (Univ. Presses of Fla., 2011).

Cory M. Malcom, The History and Archaeology of the Key West Turtle Fishing Industry, Mel Fisher Mar. Heritage Soc’y, (2013)

W.N. Witzell, The Origin, Evolution and Demise of the U.S. Sea Turtle Fisheries, 56(4) Marine Fisheries Rev. 8-23 (1994).

References

This project was funded (in whole or in part) by a grant awarded from the Sea Turtle Grants Program. The Sea Turtle Grants Program is funded from proceeds from the sale of the Florida Sea Turtle License Plate. Learn more at www.helpingseaturtles.org.

[1] John J. Brice, The Fish and fisheries of the coastal waters of Florida: Letter from the commissioner of fish and fisheries, transmitting in response to Senate resolution of February 15, 1895, a report of the fish and fisheries of the coastal waters of Florida, S. Doc. No. 54-100 (1897) (available at Biodiversity Heritage Library, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/4916).

[2] Act of 1907, ch. 5669, 1907 Fla. Laws 167 (“An ACT to Protect Logger Head and Green Turtles on the Coasts of the State of Florida”).

[3] Act of 1913, ch. 6574 – No. 74, 1913 Fla. Laws, 28 (“An ACT to Regulate the Catching of Fish and Turtle in Dade County Florida”).

[4] Fla. Stat. §374.16 (1941) (Closed season for loggerhead or green turtle while out of the water; Penalty.)

[5] See George A. Dietz, Sketch of the evolution of Florida law, 3(1) Fla. L. Rev., 74-82 (1950).

[6] Id. at 79. Also see Fla. Stat. §374.16 (1949) (Closed season for loggerhead or green turtle while out of the water; Penalty.)

[7] Act of 1941, ch. 20887-No. 679, 1941 Fla. Laws 2357—58 (“An ACT for the Protection of Loggerhead and Green Turtles and Eggs and Nests of Such Turtles in all Counties in the Fourth Congressional District of the State of Florida Having a Population of More than 39,000…”).

[8] Edward M. Jackson, Florida’s General Laws of Special or Local Application, 10(1) Fla. L. Rev. 90—97 (1957); Douglass D. Batchelor, Population Statutes Under the Florida Constitution, 1 U. Miami L. Rev. 97 (1947) (Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol1/iss2/5).

[9]. Act of 1953, Ch. 27415 – No. 936, 1953 Fla. Laws 299 (“An ACT for the Protection of Loggerhead and Green Turtles, and Eggs and Nests of Such Turtles, in Brevard County, Florida, and Providing a Penalty for the Violation of the Act”).

[10] Fla. Stat. §370.12 (1953).

[11]Act of 1957, ch. 57-771, 1957 Fla. Laws 1091 (An ACT relating to Saltwater Fisheries Conservation; prohibiting the taking, killing, possessing or mutilating of any sea turtle within a certain distance from the beaches of Florida during a certain period and providing penalties for violations) (codified at Fla. Stat. § 370.12 (1957)).

[12] Act of 1959, Ch.59-927, 1959 Fla. Laws 498—99 (An ACT relating to all counties having a population of not less than six thousand one hundred (6,100) nor more than six thousand three hundred (6,300) according to the latest official state-wide decennial census; prohibiting the gigging or spearing of green turtles; providing a penalty; providing an effective date).

[13] Act of 1963, ch. 63-1662, 1963 Laws of Florida 2328—29 (“An ACT relating to and prohibiting spearfishing in salt waters lying in and adjacent to certain areas of Monroe County providing for penalty; providing for a referendum providing an effective date”).

[14] Archie F. Carr, The Zoogeograpy and Migrations of Sea Turtles, Year Book of the Am. Phil. Soc’y, 138—40 (1954).

[15] Archie F. Carr & David K. Caldwell, The Ecology and Migrations of Sea Turtles, 1: Results of Field Work in Florida, 1955, Am. Museum Novitates; no. 1793. (1956).

[16] Archie F. Carr & Robert Ingle, The Green Turtle (Chelonia Mydas Mydas) in Florida, 9(3) Bull. of Marine Sci. of the Gulf and Caribbean 315-20. (1959).

[17] Stephen P. Geiger, In Memoriam Robert M. Ingle 1917–1997, 42(3) J. of Shellfish Rsch. 343—50 (2023).

[18] Robert M. Ingle & F. G. Walton Smith, Sea turtles and the turtle industry of the West Indies, Florida, and the Gulf of Mexico (1949).

[19] Archie F. Carr, The Windward Road Adventures of a Naturalist on Remote Caribbean Shores (1956).

[20] Frederick R. Davis, The Man Who Saved Sea Turtles Archie Carr and the Origins of Conservation Biology (2007).