A juvenile sea turtle is pulled from the Gulf of Mexico during the 2010 Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. Photo credit: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

To tread on earth with darkness soft

leaves not the night asunder

and preserves the stars and moon aloft,

and obsoleted wonders.[i]

-Blair Witherington

Introduction

In Part I of this blog segment, we reviewed the emerging science and early policy history of sea turtles and lighting. We concluded Part I with adoption of the first local ordinances regulating lighting along Florida’s beaches. In Part II, we focused on emerging state regulation of lighting through state permitting and the emergence of the state framework to address lighting in the context of continued advances in sea turtle science and lighting technology. We also explored the role of endangered species protections on lighting policy. In Part III, we describe the significance of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill disaster recovery plan for sea turtle lighting policy and then return to the effort to update the State’s model lighting ordinance, which culminated in adoption in 2020.

Disaster Strikes…And the Lights Dim

For marine conservationists, April 20, 2010 will always be one of those days of infamy that allows one to vividly recall where you were and what you were doing when the news came through – what psychologists describe as a “flashbulb memory.”[ii] That was the day oil and natural gas began gushing freely from the Deepwater Horizon oil platform, beginning an agonizing stretch of time that would stretch for 87 days, slicking the northern Gulf of Mexico and threatening the estuaries and beaches of Florida and other Gulf states. Sea turtles were among the species most at risk.[iii] But it is not the spill, but the recovery, that sea turtle lighting specialists will remember.

Perhaps America’s greatest unnatural disaster yielded a silver lining for sea turtles.[iv] When talks turned to settlement, sea turtles were near the front of the line. Six years after oil first spilled into the Gulf, a comprehensive 20-billion-dollar settlement was reached.[v] Among the “buckets” of funds that resulted from the settlement of the largest natural resources damages award in history was one entitled the Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund, earmarked for distribution by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation.[vi] After some early successes from an initial wave of “pre-settlement” oil spill funding, [vii] NFWF invested heavily in projects to retrofit private beachfront properties to more “sea turtle-friendly” lighting alternatives.[viii] The decision to make this sort of investment of oil spill monies had both a science and a policy rationale. From a scientific standpoint, scientists estimate that as many as 165,000 sea turtles were lost due to the spill.[ix] As a recovery strategy, eliminating hatchling mortality on and near the beach would serve to mitigate that direct loss, contributing to recovery. From a policy perspective, most state and local lighting regulations primarily address new construction. Requiring existing properties to retrofit lighting can be legally problematic. As a result, the influx of funds from the oil spill provided a unique and durable opportunity to both fill a policy gap and achieve restoration goals. Funds to oversee the retrofit program were awarded to the Sea Turtle Conservancy, which to date has amounted to nearly ten million dollars, spread over three phases. Property owners are required to maintain their sea-turtle friendly lighting for a minimum of ten years.[x]

The oil spill and the infusion of funding for sea turtle recovery through retrofitting coincided with the period when the commercial viability of LED lighting was reached.[xi] As one author noted: “LED technology is changing everything we thought knew about lighting and allows designers to precisely target light in the intended area.”[xii] Over time, LED lighting became available in all colors of the spectrum (and hence wavelengths acceptable to sea turtles) and reduced the need to compensate for “lumen depreciation” over time.[xiii] Lumen depreciation required manufacturers to build added light intensity into bulbs to compensate for degradation of that intensity over time.[xiv]

The long-term energy and cost efficiencies of the relatively new but still costly LED lighting technology made the retrofitting program an easier sell for beachfront property owners, especially when it helped overcome the initial investment.

As of 2024, STC has completed 327 retrofits on Gulf Coast properties with oil spill settlement funds.[xv] This is a significant figure given that in 2011 FWC had estimated there were between 700 and 1000 “problem properties” along the Florida Coast.[xvi] Estimating aggregate disorientations and misorientations that have been averted because of the retrofit program represents a significant challenge, however. STC conservatively estimates that the retrofits conducted between 2018 and 2023 have enabled as many as 125,500 sea turtle hatchlings to find the sea without being disoriented.[xvii] More reliable data comes at the individual property level, where the data shows dramatic declines in disorientations on retrofitted properties, sometimes reaching zero.[xviii]

Bringing technology-based ecological restoration to scales that matter has been challenging for the conservation community, especially in the marine environment.[xix] The Gulf spill sea turtle-friendly lighting retrofit program provided the opportunity to demonstrate at scale what the confluence of science and technology could do for species conservation in the case of sea turtles.

STC retrofitted this single-family home in Lee County in 2024.

The Model Sea Turtle Lighting Ordinance: Version 2 (non-governmental)

By 2013, the 1993 Model Sea Turtle Lighting Ordinance had grown a bit “long in the tooth” – dated by the strides in science and technology that came after it. In the aftermath of the Great Recession, coastal development was again accelerating, and with it the burden of project-by-project review of lighting plans. At the same time, aided by funding from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill disaster, the Sea Turtle Conservancy had developed substantial in-house expertise and a robust lighting retrofit program. FWC began the process of creating its own lighting guidelines to aid property owners required to undergo review pursuant to the CCCL and ERP permitting programs. In 2014, Blair Witherington, now with the FWC Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, private sector colleague Erik Martin and released the second edition of their 1996 “science-to-policy” publication “Understanding, Assessing and Resolving Light Pollution Problems on Sea Turtle Nesting Beaches,” adding Robbin Trindell as a co-author.[xx]

All the emphasis on lighting in this period led the Sea Turtle Conservancy to reach out to the University of Florida law school’s Conservation Clinic to discuss a project aimed at revising the 1993 model ordinance. This dovetailed with empirical work on lighting policy being done by a Ph.D. student under the supervision of sea turtle biologist and UF faculty member Dr. Ray Carthy.[xxi] According to McCray, by 2013, the number of local governments that had adopted sea turtle lighting ordinances had risen to 82, most based on the outdated 1993 model. This presented a problem because local governments could point to the adoption of the 1993 model as evidence of their compliance with existing law, even though DEP considered the ordinance advisory only. McCray found that only 15 jurisdictions had updated their ordinances since 2000.[xxii] In addition, McCray pointed out that the extent to which local governments adopted some or all of the components of the 1993 law also varied.[xxiii] McCray also found that few local ordinances regulated light intensity or wavelength, despite the best available science and technology, relying instead on required shielding and visibility from the beach. McCray did note some improvement in ordinances over time.

With McCray’s work as the foundation, the law clinic drafted an updated annotated model code reflecting the most recent science and technology.[xxiv] The ordinance used a land use planning concept known as an overlay district to capture all properties with lighting that reaches the beach or is visible from the beach regardless of actual proximity to the beachfront. The Clinic’s model posited two regulatory alternatives, one based on an “objective” theory of “light trespass” and the other based on the subjective observation of light from the beach. The model did not distinguish between existing and new construction. While it remained a non-regulatory, non-governmental instrument, sea turtle advocates and some local governments turned to it for guidance in updating their codes. At least one local government, Holmes Beach, adopted much of it verbatim.[xxv]

Both of these reports served as baseline upon which the 1993 Model was updated in 2020.

The Model Lighting Ordinance: Version 3

In 2018, biologists from FWC concluded it was finally time to update the model ordinance that had been on the books since 1993. They recruited the UF Law Clinic that had drafted the 2014 non-governmental model to support their effort to draft a new rule-based model. While FWC led the reform effort, the rule had been originally promulgated by DEP when the marine turtle program was housed in that agency. Thus, DEP would ultimately have to agree to amend their rule, which they did. After a workshop that involved consensus revisions to the non-governmental model, a new draft model ordinance was proposed.[xxvi] A sticking point in the negotiations came with interior lighting and the level of window tinting that would be recommended.[xxvii] Existing rules specified 45% (measured a percentage of light transferred from inside to outside),[xxviii] which biologists came to believe was insufficient. Both the non-governmental model ordinance and FWC biologists called for a much darker 15%.[xxix] Ultimately, the decision was taken to keep it at 45% to remain consistent with DEP coastal construction rules.[xxx] However, the discussion led to support for additional research to provide the data to back up the belief of the scientists that 45% did not fully prevent disorientation or misorientation.[xxxi] Characterized as “General Guidance to Local Governments,” the final updated Model Lighting Ordinance was incorporated by reference and became effective in December 2020.[xxxii]

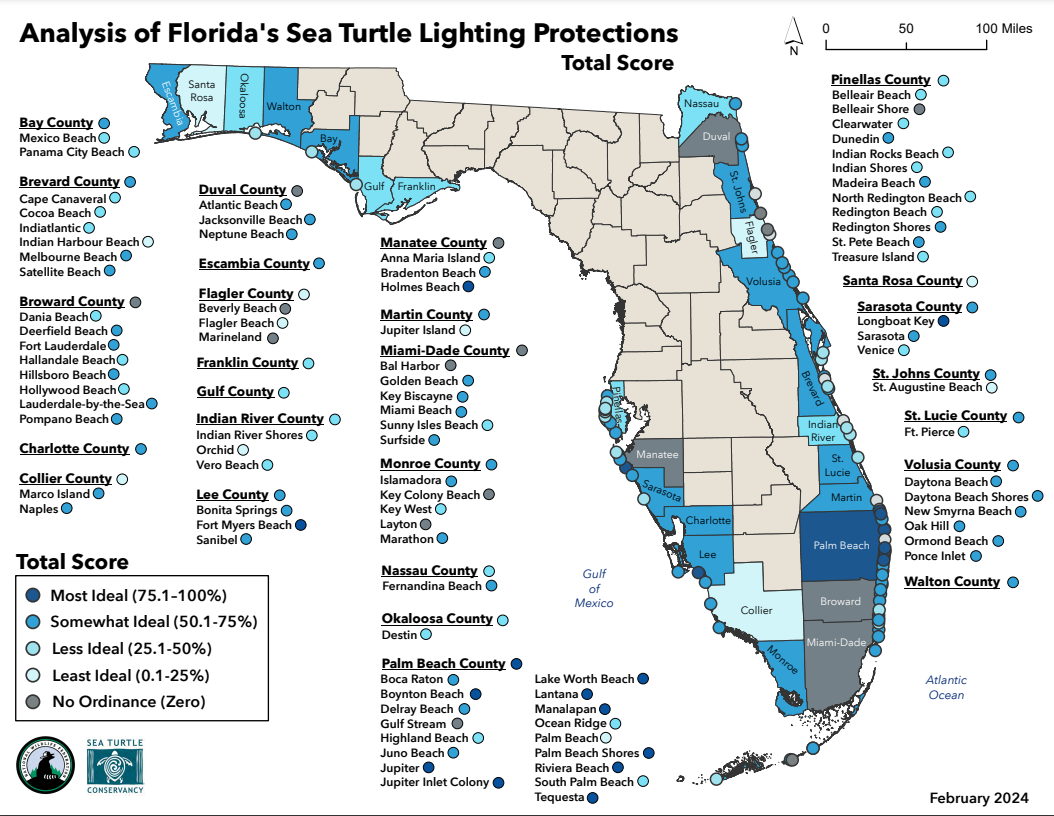

In 2022, the National Wildlife Federation and the Sea Turtle Conservancy and conducted another statewide survey and analysis of coastal local government lighting ordinances to track the adoption of, and conformity with, the 2020 model ordinance.[xxxiii] By this point the number of coastal local governments that have adopted lighting ordinances exceeded one hundred. Nevertheless, the analysis found that the quality of those ordinances varied substantially, with less than 20% adequately mirroring the state recommended model ordinance language, and only a little more than 25% adequately implementing their ordinances.[xxxiv]

Preliminary results of STC and NWF’s analysis of existing lighting ordinance language and enforcement as of February 2024.

Conclusion

Lighting remains a significant source of sea turtle hatchling mortality and continues to impact adult beach selection. Even so, fueled by the confluence of science, technology and opportunity, the policy response to the impact of beachfront lighting on adult and hatchling sea turtles remains a “bright spot” in sea turtle conservation, and endangered species conservation more broadly.

Postscript

Despite several decades of laws and regulations governing lighting along Florida’s coast there have been surprisingly no direct challenges to their legality. However, in 2024 a developer in Naples, Florida employed a seldom used tool under Florida administrative law to question the Department of Environmental Protection’s interpretation of its jurisdiction under the Coastal Construction Control Line Program (CCCL) and the Marine Turtle Protection Act. The developer, in the process of seeking a CCCL permit, sought a “Declaratory Statement” concerning the validity of the Department’s rules and interpretation of its rules implementing the two statutes.[xxxv] The proposed development straddles the CCCL, such that part of the development lies landward of the line, which the developer argued is beyond the jurisdiction of the Department under the CCCL Program.[xxxvi] In addition, the Developer proposed to install a seasonal “dual lighting system,” which would deploy sea turtle friendly lighting during the statutorily defined nesting season (), and use ordinary white light outside of the nesting season.[xxxvii] Finally, the developer questioned the authority of the Department to regulate lighting outside of “nesting areas of the beach,” even when the lighting itself is visible from the beach.[xxxviii]

The Department defended its rules and the interpretation of those rules in each instance. The Department concluded it has a legal obligation to consider the whole development when regulating lighting regardless of whether parts of the development are landward of the CCCL.[xxxix] The Department further concluded that its statutory and regulatory authority to condition a permit on the “nature, timing and sequence of construction of permitted activities” to protect sea turtles is not limited to the nesting season.[xl] The Department also stated it has the authority to regulate lighting regardless of whether the area from which the light source emanates is “directly visible from the beach,” as long as the light from the source itself is directly visible from the beach.[xli]

Because the request for a declaratory statement came in the context of an ongoing permit process, the Department noted that its decision to issue a permit had not been made, and depended upon factual submissions by the petitioner in response to the Department’s requests for additional information.[xlii]

DIGGING DEEPER

Effects of the Deepwater Horizon Spill on Protected Marine Species, Vol. 33 Endangered Species Research (2017) https://www.int-res.com/abstracts/esr/v33/

Jessica R. Henkel & Alyssa Dausman, A short history of funding and accomplishments post-Deepwater Horizon, 88 Shore & Beach (2020).

Blair E. Witherington et al., Understanding, Assessing, And Resolving Light-Pollution Problems on Sea Turtle Nesting Beaches. 2 Fla. Fish and wildlife Inst. Technical Rep. TR-2 (2014). https://www.widecast.org/Resources/Docs/Witherington&Martin%20(2014)%20Beachfront%20Lighting%20Manual%20(ENG).pdf

Barshel N., R. Bruce, C. Grimm, D. Haggitt, B. Lichter, and J. McCray. 2014. Sea turtle friendly lighting. A model ordinance for local governments. Gainesville, FL., Levin College of Law, Conservation Clinic, University of Florida. Available at https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/35334

See Jame E. McCray, “Sea Turtle Friendly Lighting in Florida: A Multi-Level Evaluation of Policy Implementation and Effectiveness” (2018) (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Florida).

[i] See Blair E. Witherington et al., Understanding, Assessing, And Resolving Light-Pollution Problems on Sea Turtle Nesting Beaches. 2 Fla. Marine Rsch. Inst. Technical Rep. 1, vii (1996).

[ii] Wendy L. Patrick, Why We Recall Where We Were When We Heard Shocking News, Psych. Today (Sept. 12, 2020), https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/why-bad-looks-good/202009/why-we-recall-where-we-were-when-we-heard-shocking-news.

[iii] See Danielle Bailey et al., Sea Turtles and the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill, Sea Grant: Miss. – Ala. (2021), https://masgc.org/oilscience/oil-spill-science-sea-turtles.pdf.

[iv] See Brianna Navarre, These Are 10 of the Worst Man-Made Disasters in U.S. History, U.S. News (Mar. 7, 2023, at 4:43 PM), https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/slideshows/10-of-the-worst-man-made-disasters-in-u-s-history?slide=11.

[v] See Jessica R. Henkel & Alyssa Dausman, A short history of funding and accomplishments post-Deepwater Horizon, 88 Shore & Beach (2020).

[vi] See Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund, Nat’l Fish & Wildlife Found., https://www.nfwf.org/gulf-environmental-benefit-fund (last visited Dec. 6, 2024).

[vii] Karen Shudes, Addressing Florida’s Beachfront Lighting Program, Velador Newsletter (Sea Turtle Conservancy) (2011), https://conserveturtles.org/11433-2/.

[viii] Keeping Sea Turtles in the Dark, Nat’l Fish & Wildlife Found., https://www.nfwf.org/media-center/featured-stories/keeping-sea-turtles-dark#:~:text=Artificial%20lights%20near%20nesting%20beaches,from%20coming%20ashore%20at%20all (last visited Dec. 6, 2024).

[ix] See Kaitlin E. Frazer et al., Chapter 26: Impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on marine mammals and sea turtles to Steven A. Murawski et al., Deep Oil Spills: Facts, Fate, and Effects (2020).

[x] Sea Turtle Conservancy Lighting Retrofit Grant Agreement Template. On file with the authors.

[xi] See Sussan W. Sanderson & Kenneth L. Simmons, Light Emitting Diodes and the Lighting Revolution: The Emergence of a Solid State Lighting Industry, 43 Rsch. Policy 1730, 1730 (2014).

[xii] See Marty Cole et al., Led Lighting. Minimizing Ecological Impact without Compromising Human Safety, IEEE IAS Petroleum and Chem. Indus. Technical Conf., 107, 111 (2021).

[xiii] Id. at 111.

[xiv] Id.

[xv] See Beachfront Lighting: Lighting and Dune Projects, Sea Turtle Conservancy, https://conserveturtles.org/beachfront-lighting-lighting-and-dune-projects/ (last visited Dec. 8, 2024).

[xvi] Shudes, supra note 70.

[xvii] Email communication with Stacey Gallagher, Sea Turtle Conservancy (Nov. 12, 2024).

[xviii] Email communication with Stacey Gallagher, Sea Turtle Conservancy (Nov. 12, 2024).

[xix] See Avigdor Abelson et al., Challenges for Restoration of Coastal Marine Ecosystems in the Anthropocene, 7 Frontiers in Marine Sci. 1, 1 (2020).

[xx] Blair E. Witherington et al., Understanding, Assessing, And Resolving Light-Pollution Problems on Sea Turtle Nesting Beaches. 2 Fla. Fish and wildlife Inst. Technical Rep. TR-2 (2014).

[xxi] See Jame E. McCray, “Sea Turtle Friendly Lighting in Florida: A Multi-Level Evaluation of Policy Implementation and Effectiveness” (2018) (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Florida).

[xxii] Id. at 43.

[xxiii] Id. at 25.

[xxiv] Barshel N., R. Bruce, C. Grimm, D. Haggitt, B. Lichter, and J. McCray. 2014. Sea turtle

friendly lighting. A model ordinance for local governments. Gainesville, FL., Levin College of Law, Conservation Clinic, University of Florida. Available at https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/35334

[xxv] See Holmes Beach, Fla., Ordinance No. 14-08 (March 11, 2014).

[xxvi] See Fla. Admin. Code Ann. r. 62B-55.002-2 (2020).

[xxvii] Interview by Stacey Ghallager with Robbin Trindell, Biological Administrator, Fla. Fish and Wildlife Conservation Comm’n (February 28, 2024).

[xxviii] Id.

[xxix] Barshel et. al, supra note 24, at 26; Witherington et al., supra note 20, at 24.

[xxx] Interview by Stacey Ghallager with Robbin Trindell, Biological Administrator, Fla. Fish and Wildlife Conservation Comm’n (February 28, 2024).

[xxxi] Id.

[xxxii] See Fla. Admin. Code Ann. r. 62B-55.004 (2020).

[xxxiii] Sea Turtle Conservancy & Nat’l Wildlife Fed., Analysis of Florida’s Sea Turtle Lighting Protections (2022),

https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/69515a3573bb4c4e99a93d2ebefc81cc/

[xxxiv] Id.

[xxxv] In re: Vanderbilt Naples Holdings, LLC, at 3 (Petition for Declaratory Statement, Fla. Dep’t of Env’t Protection 2024).

[xxxvi] Id. at 6.

[xxxvii] Id. at 10.

[xxxviii] Id. at 12.

[xxxix] In re: Vanderbilt Naples Holdings, LLC, No. 24-1732 at 4 (Final Order Granting Petition for Declaratory Statement, Fla. Dep’t of Env’t Protection 2024).

[xl] Id. at 5-6.

[xli] Id. at 7.

[xlii] Id.