Sea Turtle Conservation in Florida: Part I

So Excellent a Fishe:

The Early History of Sea Turtle Conservation in Florida

Part I

Thomas T. Ankersen, Professor Emeritus

University of Florida Levin College of Law

Introduction – When is a turtle a fish?

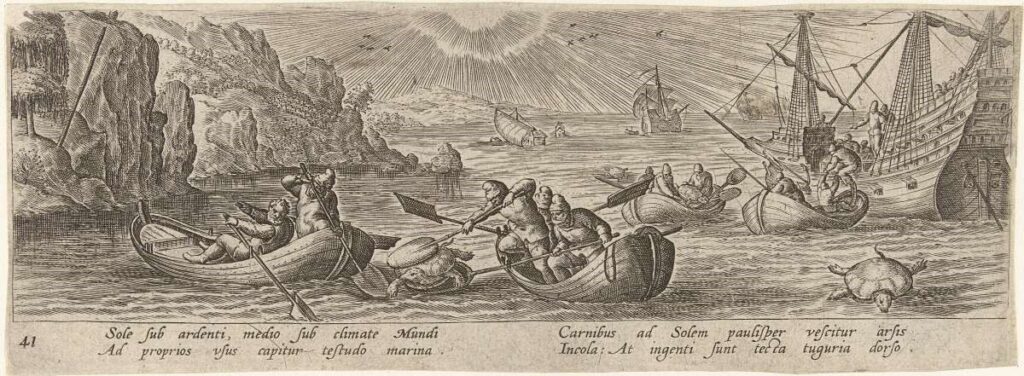

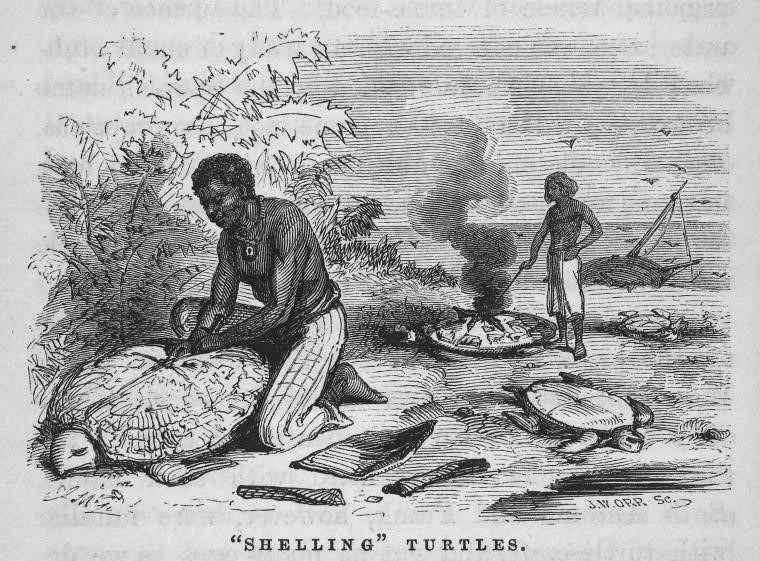

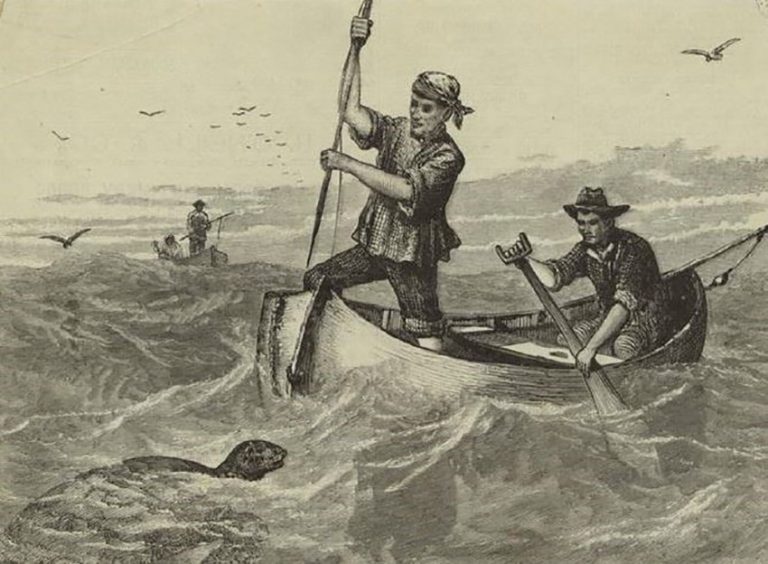

Long before sea turtles were revered as charismatic megafauna worthy of protection in their own right, they were a valuable source of protein that could be counted on by both indigenous cultures and early colonial maritime powers.[1] In 1513, Ponce de Leon reputedly reprovisioned with more than one hundred sea turtles for his return to Spain at a tiny archipelago south of Key West.[2] He would name them “Las Tortugas”(The Turtle Islands), and they would become a part of Spanish Florida. As the colonial powers overwhelmed tropical regions, decimating indigenous populations, sea turtles quickly grew in importance as a commodity for both local and transatlantic trade. This led to the gradual development of a fisheries-based approach to sea turtle conservation.

The Colonial Era – “So Excellente a Fish”

The regulation of sea turtles in western culture dates to at least 1620 when the British colonial government of Bermuda bemoaned the wanton destruction of the Green Turtles that found their way north to the tiny British island protectorate, attracted by lush sea grass beds and near tropical waters the Gulf Stream. The Old English text from a 1620 Bermudian law, titled “AN ACT AGYNST THE KILLINGE OF OUER YOUNG TORTOYSES,” provided both the title and the forward to Archie Carr’s collection of natural history essays titled “So Excellente a Fishe.”[3] Management of sea turtles as a fishery would serve as the basis for sea turtle “conservation” for the next 350 years, until global depletion of sea turtle populations rendered them commercially extinct, and the global species protection movement of the early 1970s rescued them from biological extinction. While it is beyond the scope of this project to trace the colonial lineage of sea turtle exploitation, suffice it to say trade in sea turtles quickly followed the westward expansion of the great colonial powers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[4]

Florida’s Territorial Years (1821-1845): Florida-First Protectionism

Efforts to regulate trade in sea turtles in Florida predate statehood. As the newly independent United States of America added Florida as a territory in 1821, a variety of maritime conflicts arose with its close neighbor, the British colony of the Bahamas. During Spanish rule, Bahamian fishermen had been accustomed to fishing in Florida waters, and hunting turtles and their eggs on Florida beaches. As conflict between the new U.S. Territory and the neighboring crown colony mounted, the Governor of the Bahamas reached out to the U.S. State Department to negotiate a treaty with the United States to allow Bahamian fishermen to continue taking turtles from U.S. and Florida waters and beaches.[5] Florida’s territorial governor implored the U.S. to ignore this request and protect what he regarded as a valuable economic asset to the Territory, and within the authority of the Territory to regulate for its own interests.[6]

At the same time, the Territorial government enacted Florida’s first sea turtle management law – “An Act for the Protection of the Fisheries on the Coasts of Florida, and to Raise Revenue Therefrom.”[7] The law required foreign vessels to register in Florida, and to land their catch – including sea turtles – in Florida. These requirements greatly diminished Bahamian interest in fishing in Territorial waters. The Territorial Governor was authorized to name one or more “fish commissioners” to implement the law. Interestingly, the law also forbade fishermen from employing, trading, or taking on board Seminole Indians, some of whom had just concluded the Treaty to end the First Seminole Indian War. Penalties for violating the Fisheries Act included fines and vessel forfeiture. Over the ensuing years, many Bahamian turtle fishers took residence in Florida to continue to fish the State’s waters.[8] Even so, entreaties for fishery access from the Bahamian government to the U.S. government continued (albeit without success), as the issue of fishing and turtles grew increasingly enmeshed in concerns over slavery (prohibited in the Bahamas), aid and comfort to the Seminoles (the Seminole Indian Wars raged in this period), and illegal competition for “wrecking” rights (salvage).[9]

Statehood (1845) – 19th Century: Protectionism – Florida first

When Florida became a state in 1845, it re-adopted many of its territorial laws to reflect the new sovereign state’s administrative and judicial framework, including the 1832 Territorial Fisheries Act. [10] Provisions of the law that addressed the Seminoles were tightened to preclude any interactions with the Tribe by fishers.

In 1860, all prior fisheries laws were repealed, and a new law was enacted.[11] Provisions regarding the Seminoles were dropped as the issue’s immediacy faded. A new provision in the 1860 law clarified the State’s maritime jurisdiction and prohibited out of state vessels from taking fish or turtles in waters within “one marine league” (three nautical miles) of the coast, which at the time was also considered the limits of the U.S. Territorial Sea (it is now 12 miles).

Additionally, the 1860 fisheries law specifically prohibited any person, citizen, or non-resident, from “catching fish for the roes only, or turtles for the eggs only, or in any manner wantonly destroying the fish or turtle on the coast of this State.” Under this statute, even resident Floridians were prohibited from engaging in these activities, perhaps reflecting concerns over the biological significance of gravid adults to the population at large. Throughout this period, until the turn of the century, the State of Florida continued a turtle fishery policy premised largely on vessel licensing. In 1874, the State imposed a licensing requirement on all vessels fishing for turtle, oysters, and sponges, with escalating fees by weight beginning with boats greater than 10 tons.[12] By the turn of the century, pressure on turtle and other fisheries began to manifest in diminished harvests, catching the attention of federal fisheries managers. The State’s population at the time was scarcely half of million.

Source: New York Public Library Digital Collections, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-08f7-a3d9-e040 (accessed 6 June 2020).

An Early Wake-Up Call: The 1897 Fisheries Report

A remarkable 1897 congressionally mandated report on the fisheries of Florida sounded the first alarm on overfishing of sea turtles (and other species) in the state and presaged the passage of what was likely the first law to protect nesting sea turtles in the state in 1907. The report, titled “The Fish and Fisheries of the Coastal Waters of the State of Florida” and written by United States Commissioner of Fisheries J.J. Brice, surveyed the status of the State’s fisheries, including the turtle fishery.[13] The report suggests a rudimentary but growing knowledge of sea turtle nesting behavior – discounting one theory that female turtles return to the beach to escort their hatchlings back to the sea.

Referring to the Green Turtle, the report states: “Overfishing and the destruction of its eggs have greatly reduced its abundance in this State, and the annual catch is now much less than formerly.”

Beyond the reduction in numbers of turtles, the report also highlights a drop in average weight of landed turtles, noting that in some parts of the state “where fishing has been excessive… it is under 50 pounds.” The report identifies the major centers of turtle fishing at the time, including: the Indian River Lagoon area, Biscayne Bay, Key West and the Lower Keys, Tampa Bay, and the Cedar Keys, noting its decline in each and their effective demise in Tampa Bay.

The report concludes: “The Green Turtle, one of the State’s most valuable fishery products, needs protection to prevent its extermination.” The report recommended a moratorium on taking turtles during the nesting season, creating a minimum weight limit to protect juvenile turtles, and a prohibition on “the pernicious and destructive practice of gathering the eggs of [Green] and loggerhead turtles.” Despite this dire warning, both the harvest and the resulting population decline continued. At the time, the state was home to only 500,000 people. Clearly, there was something about the nature of the sea turtle’s biology which did not lend itself to continuing harvest.

In 1907, the Florida legislature acted on part of one of the Report’s conclusions and passed a statute prohibiting taking, killing, mutilating or “in any wise destroying any logger head [sic] or green turtle while any such turtle is laying or found out of the waters or upon the beaches of the State of Florida during the months of May, June, July and August of any year.”[14] The 1897 U.S. Fish Commissioner’s Report had not distinguished land from water in its recommendation, but the state legislature chose only to limit harvest on land. Despite its impact on the turtle population, in-water turtle fishing during the nesting season would continue well into the 20th century, much to the chagrin of prominent sea turtle biologists such as Archie Carr.

Coming Next

In our next blog post, we will track the sporadic development of geographically localized sea turtle legislation in the early to mid-20th century, as legislators sought to satisfy the needs of the fishery, while attempting to address continuing declines in sea turtles in Florida. We will then turn to the growing movement to protect sea turtles in Florida and globally, as calls to protect imperiled species more generally gained momentum and scientists gained a deeper understanding of sea turtle biology.

Digging Deeper

Readers interested in digging deeper into the literature on sea turtle during the Age of Exploration, the Colonial Era and early Florida history can find more in several excellent publications.

Alison Rieser. The Case of the Green Turtle: An Uncensored History of a Conservation Icon, 2012.

James Parsons. The Green Turtle and Man. (Gainesville, University of Florida Press, 1962.

Archie Carr. Handbook of Turtles: The Turtles of the United States, Canada, and Baja California. Cornell University Press, 1995.

Robert M. Ingle. Sea Turtles and the Turtle Industry of the West Indies, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico, University of Miami Press, 1974.

Karl Offen. “Subsidy from Nature: Green Sea Turtles in the Colonial Caribbean.” Journal of Latin American Geography, vol. 19, no. 1, Jan. 2020.

References

[1] See generally Karl Offen, Subsidy from Nature: Green Sea Turtles in the Colonial Caribbean, 19 J. of Latin Am. Geography, Jan. 2020, at 182, https://doi.org/10.1353/lag.2020.0025; Lynn B. Harris, Maritime Cultural Encounters and Consumerism of Turtles and Manatees: An Environmental History of the Caribbean, 32 Int’l J. of Mar. Hist., November 2020, at 789, https://doi.org/10.1177/0843871420973669.

[2] Donna J. Souza, The Persistence of Sail in the Age of Steam (1998)(Chapter 9, The Dry Tortugas). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0139-2_2. The Tortugas would later become the Dry Tortugas to remind sailors there was no freshwater on the islands.

[3] Archie Carr, So Excellent a Fishe: The Natural History of the Sea Turtle (2011).

[4] For a depiction of the sea turtles in the age of exploration through an artistic lens, see Erma Hermens, Crossing and Turning: the Sea Turtle Trade in the 17th Century, Looking Through Art Blog (June 3, 2020), https://lookingthroughartblog.wordpress.com/2020/06/03/crossing-and-turning-the-sea-turtle-trade-in-the-17th-century/.

[5] The Territorial Papers of the United States (The Territory of Florida, 1828-1834), 24 The Nat’l Archives, 557 (1959).

[6] Report of James D. Westcott, Jr., Secretary & Acting Governor to Territorial Legislative Council Journal of the Proceedings of the Legislative Council, 10th Sess., at 5, (Jan. 2, 1832).

[7] An Act for the Protection of the Fisheries on the Coasts of Florida, and to raise revenue therefrom, 57 Acts of the Legislative Council of the Territory of Florida, at 82 (1832).

[8] Alison Reiser, The Case of the Green Turtle: An Uncensored History of a Conservation Icon 21-22 (2012).

[9] 32d Cong., 2d. Sess. Executive Documents of the United States, (1852-53).

[10] An Act for the Protection of the Fisheries on the Coast of Florida, ch. 34,1845 Fla. Laws 67.

[11] An Act to Regulate Fishing on the Coast of the State of Florida, ch. 1,121, 1860 Fla. Laws 67.

[12] An Act for the Assessment and Collection of Revenue, ch. 1976, 1874 Fla. Laws 13.

[13] John Jones Brice, The Fish and fisheries of the coastal waters of Florida: Letter from the commissioner of fish and fisheries, transmitting in response to Senate resolution of February 15, 1895, a report of the fish and fisheries of the coastal waters of Florida, S. Doc. No. 54-100 (1897) (via Biodiversity Heritage Library, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/4916 )

[14] An Act to Protect Logger Head and Green Turtles on the Coasts of the State of Florida, ch. 5669, 1907 Fla. Laws 167.

This project was funded (in whole or in part) by a grant awarded from the Sea Turtle Grants Program. The Sea Turtle Grants Program is funded from proceeds from the sale of the Florida Sea Turtle License Plate. Learn more at www.helpingseaturtles.org.