Sea Turtles and Contemporary Fisheries Management Part II: State Gill Net & Longline Gear Bans

No Net Loss? Sea Turtles and Contemporary Fisheries Management

Part II: State Gill Net & Longline Gear Bans

Thomas T. Ankersen, Professor Emeritus

Katherine Pearson, J.D. Candidate

University of Florida Levin College of Law

A green turtle drowns after being trapped in a gill net. Photo credit: NOAA

Introduction

Part I of this section explored the regulatory history of Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs) and the interplay between the federal and Florida governments in regulating shrimp trawling. Although TEDs provided an effective solution to reduce sea turtle bycatch, industry resistance stalled implementation and necessitated years of negotiation, emergency rules, and judicial intervention at the state and federal levels. However, shrimp trawling has not been the only fishery-based threat to sea turtles. Part II of this series shifts focus to state-level efforts to address other hazards: gill nets and longline fishing gear. As this post will explore, Florida’s administrative efforts to curb gill net fishing failed to satisfy the public, resulting in a controversial voter referendum amending the Florida Constitution to ban all but the smallest nets. In stark contrast, state regulators passed regulations on longline fishing in state waters with comparatively little opposition or legal conflict, and federal regulators followed suit in federal waters. These regulatory developments in fisheries management have greatly reduced gill net and longline fishing as a cause of sea turtle mortality, and have likely contributed to the continuing recovery of sea turtles.

State Gill Net Bans

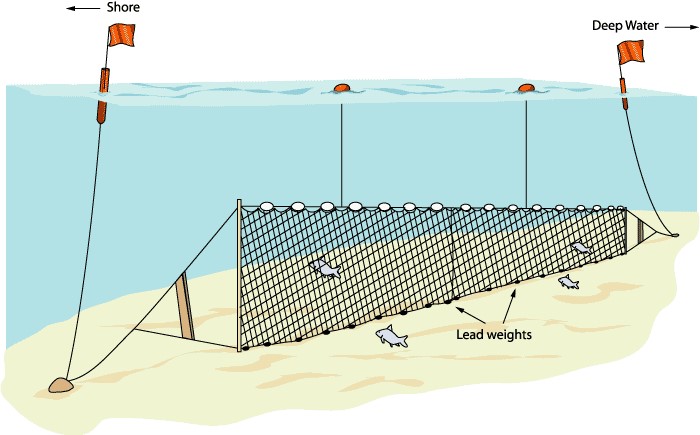

Similar to the potential dangers posed by shrimp trawlers, net fishing can also trap and drown sea turtles. Barbara Schroeder, NOAA Fisheries National Sea Turtle Coordinator, recalls that after the state and federal TED regulations went into effect, her colleagues saw fewer strandings of loggerhead and Kemp’s ridley sea turtles.[1] However, the number of stranded green sea turtles remained high, especially along the shores of Martin, Indian River, and northern Palm Beach County.[2] Her team attributed these deaths to drownings via entanglement in gill nets, as there were many instances in which abandoned gill nets washed ashore with deceased turtles tangled within them.[3]

Early State Regulatory Efforts: The East Coast Gear Rule

The Florida Marine Fisheries Commission (“Commission”) was also aware of the spike in stranded green sea turtles and the dangers that gill nets presented to this species. In an attempt to reduce the number of strandings, the Commission enacted an emergency rule on February 12, 1991.[4] The emergency rule applied to state waters in Brevard, Indian River, St. Lucie, Martin, and Palm Beach counties. It limited gill net length to 600 yards, restricted fishers to possessing two gill nets, required gill nets to be soaked and tended for no more than an hour, and mandated that gill nets be marked.[5] The stated goal of this emergency rule was to protect green sea turtles through the three fishing-heavy months that followed the rule’s adoption.[6]

On April 12, 1991, the Commission proposed making the emergency rule permanent and year-round (“East Coast Gear Rule”).[7] In an attempt to protect green sea turtles while this rule faced public comments and amendments, on May 13, 1991, the Commission renewed the prior emergency rule.[8] On July 4, 1991, the East Coast Gear Rule went into effect, providing the above year-round gear regulations in state waters in Brevard, Indian River, St. Lucie, Martin, and Palm Beach counties.[9]

Expanding Regulation: Statewide Efforts

Turning its attention statewide, the Commission proposed dual-stage regulations on January 10, 1992, to “reduce the likelihood of accidental loss or discard of fishing gear [that entangles] fish, turtles and other marine life.”[10] The first step was repealing county-specific laws to ensure conformity with step two, which was the implementation of various statewide regulations.[11] Among the proposed statewide regulations were requirements for restricting commercial gear net length to 600 yards, limiting fishers to using one net at a time, implementing a one-hour net soaking maximum, and prohibiting mesh sizes for gill and trammel nets less than three inches.[12] Unfortunately, the proposed statewide rules did not survive public hearings, and the Commission withdrew them from consideration on March 20, 1992, leaving in place the existing county-specific laws.[13]

However, the Commission did not abandon its efforts at statewide gear regulations. On July 10, 1992, the Commission proposed a similar two-part framework (“1993 Statewide Ban”) that also aimed to repeal county-specific laws that would not conform to the proposed rules.[14] The proposed regulations were largely similar to those proposed in January 1992, except they included a new restriction prohibiting the possession of more than two nets on a vessel.[15] Excluded from these regulations were fishers in transit and those in waters already regulated by the East Coast Gear Rule.[16] Portions of the rule were initially set to go into effect beginning on January 1, 1995; however, this was amended, and all sections went into effect on January 1, 1993.[17]

Conflicting Efforts: Attempts to Strengthen the East Coast Gear Rule and Weaken the 1993 Statewide Ban

Turning back to the East Coast Gear Rule, the Commission did not believe that the act was proving to be effective at reducing green sea turtle mortality during winter months.[18] To bolster existing protections for green sea turtles on Florida’s mid-east coast, the Commission proposed amendments to the East Coast Gear Rule on November 13, 1992 (“1992 East Coast Gear Rule Amendments”).[19] Specifically, between January and March, net fishing would be prohibited within one mile of the shoreline between the Sebastian Inlet and the Jupiter Inlet, an area where juvenile green sea turtles were known to feed.[20] Additionally, to further reduce the chance of contact between green sea turtles and entangling nets, the Commission proposed a year-round one-net possession limit on fishers in the state waters of Volusia, Brevard, Indian River, St. Lucie, Martin, and Palm Beach counties.[21] Moreover, the original iteration of the amendment struck the East Coast Gear Rule’s language on net length, tending, soaking, and marking requirements.[22] Nevertheless, after an amendment that attempted to stall the implementation of this regulation until January 1, 1996, the Commission withdrew the 1992 East Coast Gear Rule Amendments from consideration.[23]

While the Commission championed the plight of the green sea turtle, it also proposed rules that excluded recreational net fishers from its 1993 Statewide Ban. On December 31, 1992, the Commission proposed a rule aimed at permitting recreational fishers in the Panhandle Fishery, including state waters off of Gulf, Bay, Walton, Okaloosa, Santa Rosa, and Escambia counties, to use gill nets until January 1, 1995.[24] This rule took effect on February 24, 1993. Additionally, on May 7, 1993, the Commission proposed a similar rule for the Big Bend Region fisheries, which includes state waters off of Pasco, Hernando, Citrus, Levy, Dixie, Jefferson, Wakulla, and Franklin counties, to permit recreational gill net fishing until January 1, 1995.[25] This rule went into effect on September 1, 1993.[26]

Despite the failure of the 1992 East Coast Gear Rule Amendments to gain traction, the Commission, still seeing no meaningful reduction in green sea turtle mortality, proposed another round of amendments on June 7, 1993 (“1993 East Coast Gear Rule Amendments”).[27] The proposed regulations were originally intended to apply to fishers in the state waters of Volusia, Brevard, Indian River, St. Lucie, Martin, and Palm Beach counties.[28] They included a year-round prohibition against fishers possessing more than one net onboard.[29] Additionally, within the noted waters and seaward of the “COLREGS” Demarcation line (a line used to establish the boundary between international maritime navigation rules and federal/state navigation rules), the amendments introduced a zero-soak time requirement for gill nets, a ban on trammel and gill net usage, and a prohibition on nighttime gill net fishing.[30]

The implementation of this rule was stalled by a round of public comments and resulting amendments that reduced the 1993 East Coast Gear Rule Amendment’s coverage to the waters off of Indian River, St. Lucie, Martin, and Palm Beach counties.[31] To expedite the increased protections to green sea turtles, on October 12, 1993, the Commission enacted an emergency rule to temporarily implement the protections of the 1993 East Coast Gear Rule Amendments.[32] In December, another round of public comments and amendments ensued, followed by the permanent enactment of the 1993 East Coast Gear Rule Amendments on January 23, 1994, which applied the regulations to the waters off of Indian River, St. Lucie, Martin, and Palm Beach counties.[33]

On May 6, 1994, a proposal to further walk back protections under the 1993 Statewide Ban was introduced.[34] This proposal provided that fishers in state waters off Nassau, Duval, and St. Johns counties could ignore the 1993 Statewide Ban between January 1 and April 30 of each year.[35] During these four months, fishers seaward of the COLREGS Demarcation line would be free to possess and use more than two nets and not have to abide by tending or soaking restrictions.[36] On June 24, 1994, this proposed rule was withdrawn.[37] A later attempt to reintroduce the proposal on July 1, 1994, was also withdrawn on December 23, 1994.[38]

Despite the heightened protections imposed by the 1993 East Coast Gear Rule Amendments, on October 14, 1994, the Commission noted that these efforts were unsuccessful at reducing green sea turtle mortality in the nearshore Atlantic during the winter and spring seasons.[39] Moreover, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection reported to the Commission that while the soaking limits from the past amendment were effective when followed, the majority of fishers were not abiding by the rule.[40] Thus, the Commission proposed a new amendment to the East Coast Gear Rule that would expand the protections of the act to the state waters off Brevard County and create a seasonal green sea turtle conservation area in which fishing with any net was prohibited during January, February, March, and April.[41] However, this effort was interrupted by what would become one of the great conservation controversies in Florida history—the “net-ban” amendment to the Florida constitution.

Constitutional Protections: Amendment 3

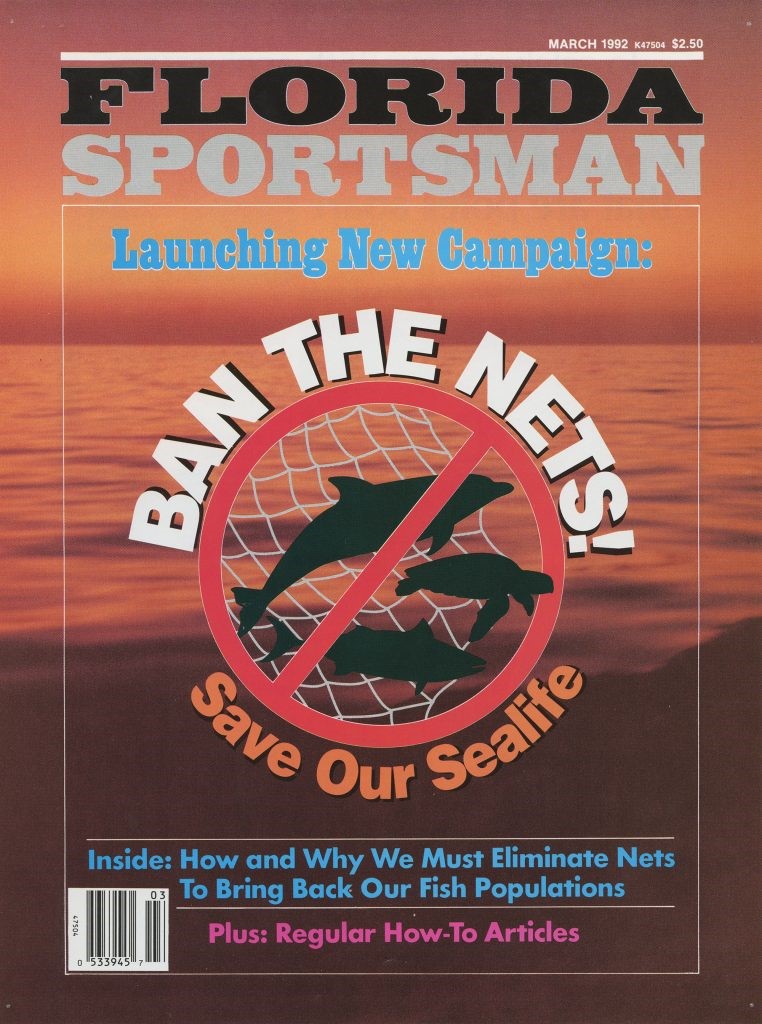

The regulatory history described above highlights the lengths that the Marine Fisheries Commission and the Department went to balance the needs of commercial net fisheries with sea turtle conservation. However, not all Floridians viewed these efforts as adequate. Chief among those was Karl Wickstrom, publisher of the Florida Sportsman, a magazine that catered to the State’s powerful recreational hunting and fishing constituency. Wickstrom first brought attention to a ban on gill nets in a 1991 column.[42] After receiving positive responses in support of the ban from readers, Wickstrom was inspired to begin the Save Our Sealife (S.O.S.) initiative, which launched a campaign in 1992 to eliminate net fishing across the state via an amendment to the State constitution (“Amendment 3”).[43] S.O.S. took issue with commercial fishermen using gill and trammel nets to contribute to overfishing, and it perceived the state agencies as failing to defend against this threat, at the expense of the lucrative recreational fishing industry, as well as incidental bycatch such as sea turtles.[44]

The S.O.S movement, led by recreational fishers, was countered by the commercial fishing industry’s Save Our Jobs and Save Your Seafood movements.[45] Commercial fishers argued that taking away net fishing would deprive them of their livelihoods.[46] They contended that this ban would remove around 40 million pounds of fresh fish from markets each year, slashing the jobs associated with this production.[47] Moreover, statistics from a Florida Department of Agriculture survey suggested that black Floridians would be particularly hard-hit by this ban, as they consumed the majority of the state’s mullet, a fish caught almost exclusively by net.[48]

To get Amendment 3 on the 1994 ballot, S.O.S. needed 400,000 signatures. During the 1992 general election, volunteers were dispersed to collect signatures.[49] In one day, they collected 200,000, half of the required amount.[50] In the following year, Wickstrom continued to write articles in support of the ban in Florida Sportsman to garner support and keep the issue in the public eye.[51] Despite the concerns and efforts of the counter-movements, the amendment easily made it onto the ballot, and on November 8, 1994, Florida voters passed the constitutional amendment, banning most gill nets from use in Florida waters.[52] This ban went into effect on July 1, 1995.[53]

Meshing Amendment 3 with State Regulations

While the Florida Marine Fisheries Commission had spent years creating a patchwork system of restrictions against gill and trammel nets, the passage of Amendment 3 made the need for these county-specific regulations obsolete. On July 5, 1996, the Commission announced its first proposal to repeal the now unnecessary county-specific regulations.[54] This impacted the latest derivative of the East Coast Gear Rule and regulations in the Big Bend and Panhandle fisheries that provided exceptions to the 1993 Statewide Ban. These changes went into effect on September 30, 1996.[55] On November 1, 1996, the Commission announced amendments to its 1993 Statewide Ban to “specify allowable net gear and necessary operational requirements for such gear in light of the adoption of [Amendment 3].”[56] The proposed rule, which effectively codified the constitutional amendment, expanded prohibitions against most gill or entangling nets in Florida waters, amending the prohibition to encompass more nets.[57] Since this constitutional net ban amendment, Florida’s regulatory framework for net fishing has not experienced any drastic changes.

Upholding Constitutionality

Since Amendment 3 passed, it has survived various court challenges, including those questioning its constitutionality. In 1999, Raymond Pringle and Ronald Crum, designers of a specific type of fishing net, argued that if their net design failed to meet the requirements of Rule 68B-4.0081, which aligned the 1993 Statewide Net Ban with the constitutional amendment, then the rule violated their constitutional rights to due process and equal protection.[58] The lower court agreed with Pringle and Crum, finding Rule 68B-4.0081 unconstitutional because it would “result in the complete deprivation of individuals’ right to earn a living.”[59] However, the appellate court vacated this decision because Pringle and Crum did not exhaust available administrative remedies, and the court, without a technical understanding of fishing gear, should have more heavily relied upon the Commission’s expertise.[60] In 2007, Ronald Crum, alongside the Wakulla Commercial Fishermen’s Association, once again challenged the constitutionality of Rule 68B-4.0081.[61] In this case, the court upheld the constitutionality of the rule by finding that evidence that the net ban had increased mullet populations was sufficient to establish a rational basis for the rule.[62] In a 2014 attempt to invalidate the 1993 Statewide Ban, the First District Court of Appeals relied on precedent to uphold the constitutionality of the ban.[63]

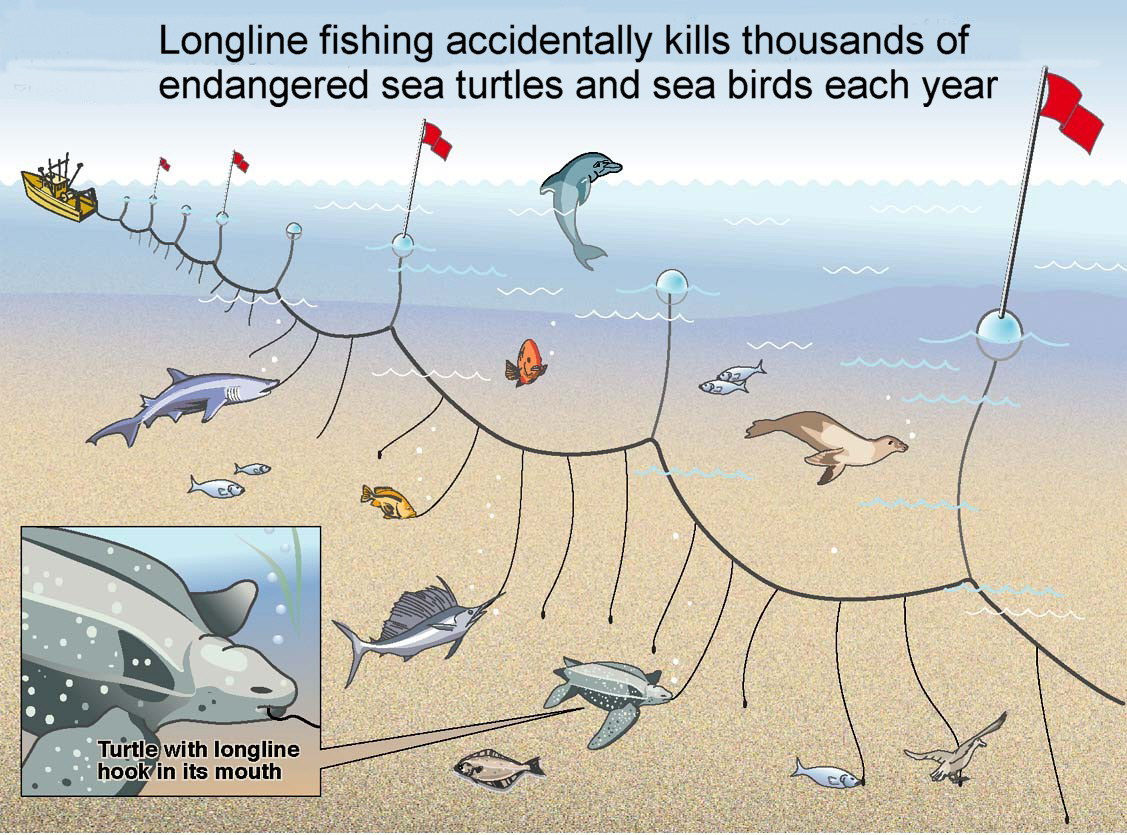

State Longline Fishing Ban

Longline fishing can also be harmful to sea turtles, as the animals can get caught on the hooks and drown or ingest the hooks and experience fatal complications.[64] As previously mentioned, the Florida Marine Fisheries Commission (“Commission”) proposed dual regulations on January 10, 1992, to “reduce the likelihood of accidental loss or discard of fishing gear [that entangles] fish, turtles and other marine life.”[65] In addition to kickstarting the 1993 Statewide Net Ban, this proposal included language to forbid the use and possession of longline fishing gear in all state waters unless a boater was only passing through.[66] Following the same history as above, this proposal did not survive public hearings, and the Commission withdrew it from consideration on March 20, 1992.[67] Four months later, the proposal was reintroduced on July 10, 1992. Without further amendments, the language restricting longline fishing gear in Florida waters was adopted on November 26, 1992, and went into effect on January 1, 1993. This regulation has not faced any notable litigation or amendments.[68] In 2001, the federal government instituted a “year-round pelagic longline fishing closure” in federal waters (out to 200 miles) off the Florida and Georgia Coast,[69] further reducing the threat of sea turtle by-catch.

While the state’s back-and-forth regulatory efforts largely shaped Florida’s gill net regulations and resulted in the constitutional net ban, the state’s longline fishing ban followed a far smoother path to adoption. Since its implementation in 1993, the prohibition on longline fishing gear has remained unchanged and unchallenged. Conversely, the gill net ban faced pushback in the courtroom, but it has survived these challenges and has not faced any major amendments since 1996.

Conclusion

Florida’s controversial constitutional net ban, perceived as an end run around the legislature and the State’s fishery management agency, continues to generate strong feelings among commercial and recreational fishers, and conservation advocates.[70] However, coupled with the restrictions on long line fishing in state and federal waters, there is considerable evidence that the overall effect on sea turtle populations has been positive. A comprehensive post-net ban review of stranded marine megafauna (1997–2009) found that only 4.8% of stranded sea turtles showed evidence of fishing-net entanglement as opposed to other causes, which the authors attributed, at least in part, to the net ban.[71] At the same time, the federal and state prohibition on long-line fishing in Florida and federal waters essentially eliminated sea-turtle bycatch.[72] Studies have also demonstrated reductions in by-catch due to changes in hook and bait regulations outside of the closed area,[73] likely further contributing to the reduction in fisheries management impacts to sea turtles in Florida, due to their highly migratory nature.

References

[1] Interview by Stacey Gallagher with Barbara Schroeder, National Sea Turtle Coordinator, NOAA Fisheries (Dec., 8, 2023).

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] 17-8 Fla. Admin. Reg. 828 (Feb. 22, 1991).

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] 17-15 Fla. Admin. Reg. 1622 (Apr. 12, 1991).

[8] 17-19 Fla. Admin. Reg. 2089 (May 10, 1991).

[9] Through this rule, the Commission repealed the Martin County Special Act, Chapter 71-770, Laws of Florida, and readopted a subsection of this law prohibiting the hauling of nets ashore. 17-15 Fla. Admin. Reg. 1622 (Apr. 12, 1991).The Commission was able to repeal an act of the Florida Legislature under the rulemaking authority of Section 2 of Chapter 83-134, Laws of Florida, as amended by Section 1 of Chapter 84-121, Laws of Florida.

[10] 18-2 Fla. Admin. Reg. 188 (Jan. 10, 1992).

[11] Id.

[12] 18-2 Fla. Admin. Reg. 195 (Jan. 10, 1992).

[13] 18-14 Fla. Admin. Reg. 2050 (Apr. 3, 1992).

[14] 18-28 Fla. Admin. Reg. 4003 (Jul. 10, 1992).

[15] 18-28 Fla. Admin. Reg. 4009 (Jul. 10, 1992).

[16] Id.

[17] 18-35 Fla. Admin. Reg. 4944 (Aug. 28, 1992).

[18] 18-46 Fla. Admin. Reg. 6918 (Nov. 13, 1992).

[19][19]Id.

[20] Id.

[21] Id.

[22] Id.

[23] 18-45 Fla. Admin. Reg. 7970 (Nov. 13, 1992); 19-16 Fla. Admin. Reg. 2185 (Apr. 23, 1994).

[24] 18-53 Fla. Admin. Reg. 8112 (Dec. 31, 1992).

[25] 19-18 Fla. Admin. Reg. 2472 (May 7, 1993).

[26] 19-33 Fla. Admin. Reg. 4657 (Jul. 20, 1993).

[27] 19-18 Fla. Admin. Reg. 2470 (May 7, 1993).

[28] Id.

[29] Id.

[30] Id.

[31] 19-36 Fla. Admin. Reg. 5063 (Sept. 10, 1993).

[32] Id.; 19-42 Fla. Admin. Reg. 6135 (Oct. 22, 1993).

[33] 19-51 Fla. Admin. Reg. 7694 (Dec. 23, 1993).

[34] 20-18 Fla. Admin. Reg. 3124 (May 6, 1994).

[35] Id.

[36] Id.

[37] 20-25 Fla. Admin. Reg. 4540 (Jun. 24, 1994).

[38] 20-26 Fla. Admin. Reg. 4699 (Jul. 1, 1994); 20-51 Fla. Admin. Reg. 9449 (Dec. 23, 1994).

[39] 20-41 Fla. Admin. Reg. 7577 (Oct. 14, 1994).

[40] Id.

[41] Id.

[42] Blair Wickstrom, Florida Sportsman: A Legacy on the Conservation Frontlines, Fla. Sportsman (Oct. 29, 2021), https://www.floridasportsman.com/editorial/florida-sportsman-conservation-record/397217.

[43] Id.; Bob Epstein, Coalition Seeks Ban on Gill-Net Fishing, Miami Herald (Oct. 22, 1992), https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&t=&sort=YMD_date%3AD&hide_duplicates=2&fld-base-0=alltext&maxresults=60&val-base-0=%22Coalition%20Seeks%20Ban%20on%20Gill%20Net%20Fishing%22&pedirect=true&docref=news/0EB347D8130A254E.

[44] Id.

[45] Alexandra M. Renard, Will Florida’s New Net Ban Sink Or Swim?: Exploring The Constitutional Challenges To State Marine Fishery Restrictions, 10 J. Land Use & Envtl. L. 273, 275 (1994-1995).

[46] Jeff Klinkenberg, Both Sides of the Net, St. Pete. Times (Oct. 23, 1994). https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&t=decade%3A1990%211990%2B%2B1999/year%3A1994%211994/stp%3ANewspaper%21Newspaper&sort=YMD_date%3AD&hide_duplicates=2&fld-base-0=alltext&maxresults=60&val-base-0=%22Both%20Sides%20of%20the%20Net%22&pedirect=true&docref

=news/0EB52D11688DEE8F.

[47] Thomas J. Murray, Net-ban proponents play on emotions and ignore science, Tampa Bay Times (Nov. 5, 1994), https://www.tampabay.com/archive/1994/11/05/net-ban-proponents-play-on-emotions-and-ignore-science/.

[48] Id.

[49] Nevin Smith, The Case of the Commercial Fisheries Constitutional Net Ban Amendment in Florida: An Illustration of the Impact of Special Interest Associations on Institutional Change (Fall, 2006) (Ph.D. dissertation, Florida State University) (on file with Florida State University Digital Repository).

[50] Id.

[51] Id.

[52] Alexandra M. Renard, Will Florida’s New Net Ban Sink Or Swim?: Exploring The Constitutional Challenges To State Marine Fishery Restrictions, 10 J. Land Use & Envtl. L. 273, 274 (1994-1995).; Fla. Const. art. X, § 16.

[53] Id.

[54] 22-27 Fla. Admin. Reg. 3951 (Jul. 5, 1996).

[55] 22-38 Fla. Admin. Reg. 5454 (Sept. 20, 1996).

[56] 22-44 Fla. Admin. Reg. 6281 (Nov. 1, 1996).

[57] Id.

[58] Fla. Fish & Wildlife Conservation Comm’n v. Pringle, 838 So. 2d 648, 649 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2003).

[59] Id. at 650.

[60] Id.

[61] Wakulla Com. Fishermen’s Ass’n, Inc. v. Fla. Fish & Wildlife Conservation Comm’n, 951 So. 2d 8, 9 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2007).

[62] Id. at 10.

[63] Fla. Fish & Wildlife Conservation Comm’n v. Wakulla Fishermen’s Ass’n, Inc., 141 So. 3d 723,729 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2014).

[64] Longline Fisheries, Sea Turtle Conservancy, https://conserveturtles.org/threat/longline-fisheries/, (last visited Mar. 25, 2025).

[65] 18-2 Fla. Admin. Reg. 188 (Jan. 10, 1992).

[66] 18-2 Fla. Admin. Reg. 198 (Jan. 10, 1992).

[67] 18-14 Fla. Admin. Reg. 2050 (Apr. 3, 1992).

[68] 18-28 Fla. Admin. Reg. 4009 (Jul. 10, 1992).

[69] Fisheries of the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and South Atlantic; Pelagic Longline Gear Restricted Area; East Florida Coast, 66 Fed. Reg. 8903 (Feb. 5, 2001), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2001/02/05/01-2840/fisheries-of-the-caribbean-gulf-of-mexico-and-south-atlantic-pelagic-longline-gear-restricted-area

[70] Bill Taylor, Stuck in the Middle of Florida’s Net Ban(2017), https://www.amazon.com/Stuck-Middle-Floridas-Net-Ban/dp/138734773X

[71] Adimey, N. M., Hudak, C. A., Powell, J. R., Bassos-Hull, K., Foley, A., Farmer, N. A., White, L., & Minch, K., Fishery Gear Interactions from Stranded Bottlenose Dolphins, Florida Manatees and Sea Turtles in Florida, U.S.A., 81 Mar. Pollut. Bull. 103 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.02.008.

[72] The Billfish Foundation, Florida East Coast Closed Zone Will Remain Closed (Sept. 5, 2018), https://billfish.org/advocacy/florida-east-coast-closed-zone-will-remain-closed/.

[73] Reinhardt, J. F., Weaver, J., Latham, P. J., Dell’Apa, A., Serafy, J. E., Browder, J. A., Christman, M., Foster, D. G., & Blankinship, D. R., Catch Rate and At‑Vessel Mortality of Circle Hooks Versus J‑Hooks in Pelagic Longline Fisheries: A Global Meta‑Analysis, NOAA Tech. Memo. (2017), https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/54468