All the Light They Can and Should Not See

All the Light They Can and Should Not See:

A Short History of Sea Turtle Lighting Science and Policy in Florida

Part I

Thomas T. Ankersen & Stacey Gallagher

August 2024

Might we masters of the light adapt,

forgo complete control,

and lessen obsolescence

lest our presence take its toll? [1]

Blair E. Witherington

Introduction

In 1879 Thomas Edison said, “Let there be light!” and there was light. It did not take long for the night skies to light up across the globe. It was not much longer before scientists recognized and began to study the effects that bringing light into darkness would have on creatures other than humans – none more than sea turtles. The story of sea turtles and artificial lighting is a case study in the fruitful intersection of science, technology, and policy. As has been so often the case with sea turtle science and policy, all roads lead to Florida, and along its beaches.

The Early Science of Sea Turtle Orientation

The science of animal orientation to external environmental stimuli had its beginnings in the early 19th Century but blossomed at the end of that century and beginning of the next, with much of the later inquiry focused on orientation to or away from light (phototaxis).[2] It did not take long for early researchers to explore the phenomenon in sea turtles. In 1907 and 1908, a Yale University Researcher named Davenport Hooker conducted crude experiments on loggerhead hatchlings at the Carnegie Institution’s Tortugas Laboratory in Florida’s Dry Tortugas.[3] Hooker made two prescient findings: 1) that the hatchlings naturally orient to diffuse light at the horizon, and 2) that “when the light of the lantern is thrown at night into one of the pens containing from 50 to 75 turtles, all orient and crawl toward the lantern and remain in the area lighted by it.”

Those two findings essentially, if simplistically, continue to explain the phenomenon of hatchling orientation to the sea—as well as the phenomena of disorientation and misorientation that contemporary sea turtle researchers and advocates know all too well. In 1922, working from the Miami Seaquarium, George Parker, Director of the Zoological laboratories at Harvard University, took some issue with these findings, concluding that slope and the broad open horizon (geotaxis) was an additional compelling factor in hatchling sea-finding.[4] In 1947, Robert Daniel and Karl Smith diminished the role of slope, and added additional context to the hatchling sea-finding mechanism, concluding that reflected light from the breaking surf serves as “the critical stimulus for both activating and guiding the ocean crawl.”[5]

From Orientation to Disorientation (and Misorientation)

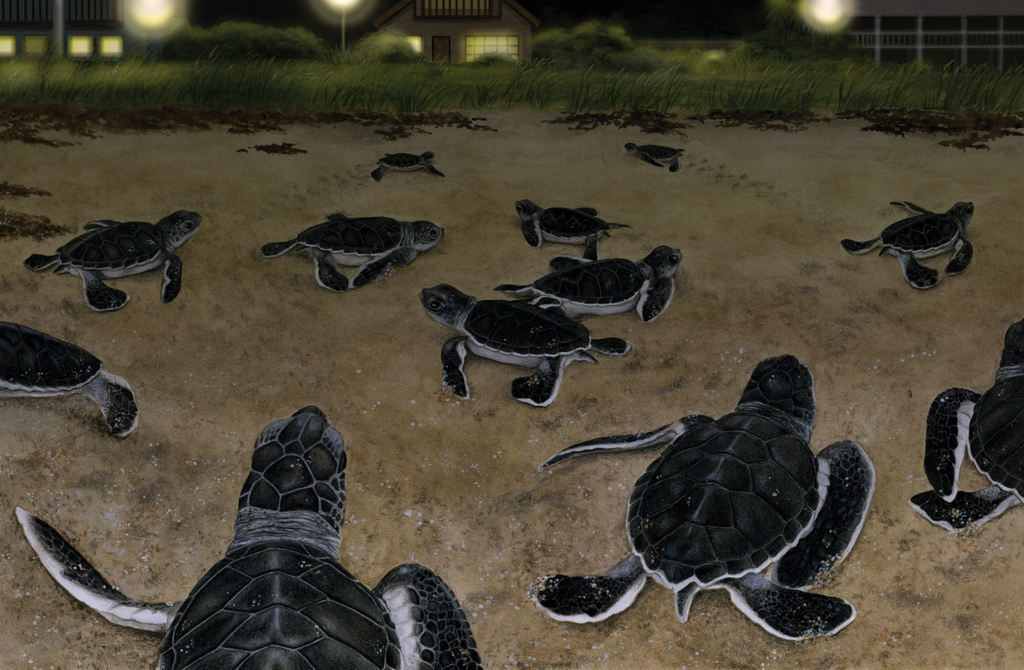

Beginning in the late 1950s as night skies continued to brighten, the scientific research emphasis began to broadly shift toward the phenomenon of animal disorientation and misorientation across taxonomic groups—described as the “light trapping effect.”[6] The two phenomena are often confused or conflated—usually toward the single term of disorientation. They are distinct, however. Misorientation refers to an animal that moves deliberately toward a source of artificial light. [7] Disorientation refers to an animal that wanders from its original destination due to the presence of artificial light.[8] A wayward hatchling turtle can do both—on the same fateful journey.

Researchers also began to focus on the causes of light-induced disorientation and misorientation in sea turtles specifically. In 1958, working in Sarawak and Malaya, John Hendrickson noted his ability to guide hatchlings “at will” with flashlights in any direction.[9] In 1959, Archie Carr and his student Larry Ogren also observed this with leatherback hatchlings in Tortuguero, Costa Rica.[10] Hendrickson also described the reluctance of adult green turtles in Sarawak to come ashore in the presence of continuous artificial lighting, the degree of which varies by species. This would be born on in subsequent research as well.[11]

Early Warnings

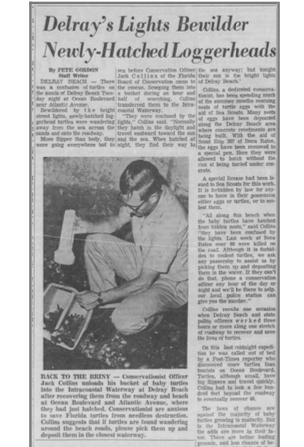

Perhaps the first alarm that would portend the future in Florida was reported in 1963 by University of Florida researcher Robert McFarlane in a short note in the herpetology journal Copeia.[12] Noting the proximity of coastal roads to urbanizing beachfront communities, in this case Fort Lauderdale, McFarlane observed a nest 30 feet from the surf and 100 feet from the adjacent highway. He reported that 95% of the hatchlings were unable to orient correctly and find the surf, finding the highway and certain death instead. Citing prior research, he attributed this to Ft. Lauderdale’s night glow and a mercury vapor streetlight on State Road A1A. Decrying the “disastrous effect of these rapidly developing resort areas adjacent to nesting beaches,” and noting the relative lack of hatchling mortality on adjacent undeveloped and unlighted beaches, he concluded, “[o]ne need only travel the shorelines of these beach resorts counting the hundreds of carcasses to realize that this is not an isolated example.” South Florida newspapers began to report on hatchling mortality as well, raising public awareness of the issue. In 1963, the Palm Beach Post reported: “In this era when baby turtles hatch they are sometimes confused by the glare of light in the sky over populated towns and cities and crawl inland to their death instead of toward the sea.”[13] In 1966, reporting on hatchling disorientation in Delray Beach, the newspaper headline read “Delray’s Lights Bewilder Newly-Hatched Loggerheads.”[14]

In 1974, Florida Atlantic University graduate student Thomas Mann quantified the extent of disorientation along six miles of South Florida beach from Fort Lauderdale to Delray Beach. He found that the “majority of hatchlings emerging on beaches nearby artificial lights sources were misoriented and usually headed inland.”[15] While not all of these meandered immediately to the highway and certain death, he speculated that the energy spent reorienting to the sea, would weaken them, and increase the likelihood of mortality as the hatchlings faced the perils of predation on the beach and in the surf zone, something that remains a continuing concern.

All the Light They Should Not See

It made sense that concerns over hatchling misorientation focused on Southeast Florida in the 1960s and early 1970s. Florida’s population doubled between 1960 and 1980, much of it centered on the tri-county Gold Coast of Dade, Broward and Palm Beach. Florida’s famed coastal highway State Road A1A, running parallel to the Atlantic Ocean, became Main Street for the rapidly developing South Florida beach towns, often forming a continuous path of development, with little but “welcome to” signs to distinguish one town from the next. In places the highway runs right along the water, providing the views that have helped to make it famous—and dangerous for sea turtles. Human public safety concerns dictated the increasing need for street lighting, and street lighting technology moved from incandescent to mercury vapor and eventually to sodium vapor.[16] Unfortunately, all these technologies share the part of the visible light spectrum that affects sea turtles, albeit to varying degrees. Subsequent research would begin to identify that part of the spectrum that most affects sea turtles, a precondition to adapting lighting technology to accommodate sea turtles.

Much of the rest of the State’s East and Gulf Coast barrier islands also began to boom in this period, if not so dramatically. Many of these barrier islands remained tenuously connected to the mainland by narrow two lane causeways with traffic-clogging drawbridges, and more distant from urban centers—some still disconnected from one another. Their time would come.

All the Light They Should Not See

Meanwhile, not content with the conclusion that light serves as the predominant mechanism to both orient and disorient sea turtle hatchlings, researchers continued to develop the science of sea-finding, focusing on both the color (wavelength) and brightness (intensity) of light. In 1968, David Ehrenfield, a student of Archie Carr, outfitted hatchlings with spectacles (if only there were photos!), and varied the spectrum of light the hatchlings were capable of seeing.[17] These experiments demonstrated that red light (the long-wavelength end of the spectrum) has a reduced effect on hatchling orientation relative to blue light at the low-wavelength end of the spectrum.[18] However, research also showed that light intensity could ultimately overwhelm color.[19] Subsequent research continued to confirm the spectral orientation of sea turtles toward long wavelength light.[20] These findings ultimately led to the prescription that would become the backbone of Florida sea turtle lighting policy: “Keep it Low; Keep it Shielded; Keep it Long.”[21]

- KEEP IT LOW: Use low mounting height, wattage, and lumens. Flood, spot, and pole lighting are highly discouraged.

- KEEP IT SHIELDED: Shield fixtures so you cannot see the source of light. Shielding also helps direct the light down to the ground where it is needed.

- KEEP IT LONG: Sea turtles are less disturbed by the long wavelengths of light (560 nanometers or longer). Narrowband long wavelength lights appear amber, orange, or red in color and not contain shorter spectrums of light.

A Broader Context: Light as Pollution

The growing concern over beach lighting and sea turtle behavior was not without context. The 1960s and 1970s was generally an era of environmental awakening. And while much of the emphasis on pollution was focused on air and water, light pollution began to receive global and national attention as well, first from astronomers, [22] but soon followed by wildlife scientists and advocates.[23] In 1987, the International Dark Sky Association, now DarkSky International, was established to advocate against light pollution.[24] Non-profit environmental education and policy advocacy was also emerging as a potent force in this period. In 1984, University of Central Florida researcher Paul Raymond published a report on hatchling disorientation supported by the Washington D.C.-based Center for Environmental Education and its “Sea Turtle Rescue Fund.”[25] The report reviewed the literature, assessed the current state of policy, and offered potential solutions.

A Policy Response Emerges

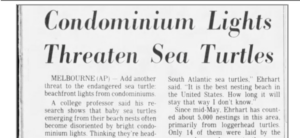

As renowned Florida historian Gary Mormino noted in his social history of Florida when describing the second half of the twentieth century, “[n]owhere was prosperity rearranging America with more force and speed than along Florida’s beaches.”[26] As barrier island populations swelled up and down both Florida coasts, beaches continued to light up and sea turtle hatchling mortality rose. This became particularly evident in Brevard County, which was continuing to experience massive growth due to the space boom. Newspapers continued to report on the annual highway carnage and the growing local environmental movement pressured political leaders to address the situation.[27] The epicenter of sea turtle nesting in Florida, Brevard’s south beaches host one of the most important nesting beaches in the Western Hemisphere.[28] Between 1978 and 1982, the two-lane causeway and drawbridge that led to Brevard’s South Beaches was replaced by a four-lane high-rise span facilitating greater access, spurring fears of rapid barrier island development.[29]

In 1982, in what appears to be the first formal local expression of public policy addressing sea turtles and lighting, Brevard County enacted a non-binding resolution requesting residents along the beach “to turn off those dwelling lights which face the shore areas in an effort to secure and protect the nests of sea turtles during the turtle crawl season.”[30] That resolution was followed by an enforceable beach lighting ordinance in 1985, one that would become the model for both the state and local governments in the coming years.[31] The ordinance, which appears to have applied only to the South Beaches, addressed both new development and existing development, with different treatment of each. It required that most lighting “not be visible from the beach,” that ocean-facing windows be tinted, and that certain fixtures be both low to the ground and low intensity, and shielded. All these requirements would eventually find their way into state law.

Perhaps serendipitously, at the time the Brevard ordinance was going into effect, a young researcher named Blair Witherington began his career in sea turtle conservation along Brevard County’s South Beaches. Witherington would go on to become one of the State’s (and world’s) leading experts on sea turtles. But in the summer of 1985, he spent his first graduate student field season assessing loggerhead and green turtle hatching production for his Master’s thesis at the University of Central Florida.[32] While he found that hatchling disorientation was significant, he also made the key finding that “the rate of hatchling disorientation was found to decrease following the enforcement of a regional ordinance restricting beachfront lighting.” Now looking back, Witherington credits the work of local natural resources and planning staff for their proactive efforts to craft a policy solution that the County’s decisionmakers could adopt.[33]

Soon thereafter, other local governments took the cue and began adopting their own ordinances modeled after Brevard’s, beginning with the beach towns in Brevard County (1986 – Melbourne Beach, Indialantic, Cocoa Beach, Indian Harbor Beach), followed by many other Atlantic coastal counties and communities, then peninsular Gulf counties and communities, and later still, Panhandle communities.

Coming Next

Part II of this blog will track the growing interest of the State of Florida in sea turtle lighting policy in the 1990s, both through encouragement to local governments and through continued research and policymaking. Part II will also discuss the role the federal Endangered Species Act and the Florida Marine Turtle Protection Act played in beach lighting policy, through rulemaking and permitting, and litigation. The science of sea-finding would continue to develop, putting a finer point on preceding research while providing confidence to policymakers that their choices would make a difference. Lighting technology too would continue to evolve, offering greater opportunities for coexistence between humans and sea turtles on darkened beaches. Finally, a massive infusion of funding from the Gulf Oil Spill settlement became available to pursue retrofits of existing lighting in buildings across Florida’s beaches, offering a natural experiment on the impact that new lighting technologies could play in both increasing adult nesting on lighted beaches and reducing hatchling mortality.

References

[1] See Blair E. Witherington et al., Understanding, Assessing, and Resolving Light-Pollution Problems on Sea Turtle Nesting Beaches, Technical Report TR-2, Florida Marine Research Institute (1996).

[2] See Gottfried S. Fraenkel & Donald L. Gunn, The Orientation of Animals: Kineses, Taxes and Compass Reactions (Dover Publ’ns 1961).

[3] See Davenport Hooker, Certain Reactions to Color in the Young Loggerhead Turtle, 3 Papers from Tortugas Lab’y Carnegie Inst. Washington 69 (1911).

[4] See G. H. Parker, The Crawling of Young Loggerhead Turtles Toward the Sea, 36(3) J. Experimental Zoology 323 (1922).

[5] See Robert S. Daniel & Karl U. Smith, The Migration of Newly-Hatched Loggerhead Turtles Toward the Sea, 106(2756) Sci. 398, 398–99 (Oct. 24, 1947).

[6] See Frans J. Verheijen, The Mechanisms of the Trapping Effect of Artificial Light Sources Upon Animals, 13 Archives Néerlandaises de Zoologie, 1–107 (Jan. 1, 1960).

[7] See Blair E. Witherington & R. Erik Martin, Understanding, Assessing, and Resolving Light-Pollution Problems on Sea Turtle Nesting Beaches, Technical Report TR-2, 13 (Florida Marine Research Institute,1996).

[8] See id.

[9] See John R. Hendrickson, The Green Sea Turtle: Chelonia Mydas (Linn.) in Malaya and Sarawak, 130(4) J. Zoology 455, 455–535 (June 1958).

[10] See Archie Carr & Larry Ogren, The Ecology and Migrations of Sea Turtles: 3 Dermochelys in Costa Rica, 1958 Am. Museum Novitates 1(Aug. 5, 1959).

[11] See Michael Salmon, Artificial Night Lighting and Sea Turtles, 50(4) Biologist 163, (Aug. 2003).

[12] See Robert W. McFarlane, Disorientation of Loggerhead Hatchlings by Artificial Road Lighting, 1963(1) Copeia 153 (Mar. 30, 1963).

[13] See Protecting Turtles is Problem, Palm Beach Post, July 21, 1963.

[14] See Pete Gordon, Delray’s Lights Bewilder Newly-Hatched Loggerheads, Palm Beach Post, Aug. 25, 1966.

[15] See Tom M. Mann, Impact of Developed Coastline on Nesting and Hatchling Sea Turtles in Southeastern Florida (Mar. 29, 1977) (M.S. thesis, Florida Atlantic University) (on file with the Florida Atlantic University Digital Library).

[16] See John A. Jakle, City Lights: Illuminating the American Night page (Johns Hopkins Univ. Press 2001).

[17] See David W. Ehrenfeld & Archie Carr, The Role of Vision in the Sea-Finding Orientation of the Green Turtle (Chelonia Mydas), 15(1) Animal Behav. 25, 25-36 (1967).

[18] See N. Mrosovsky & Sara J. Shettleworth, Wavelength Preferences and Brightness Cues in the Water Finding Behaviour of Sea Turtles, 32(4) Behav. 211 (Jan. 1, 1968).

[19] See N. Mrosovsky & Sara J. Shettleworth, Wavelength Preferences and Brightness Cues in the Water Finding Behaviour of Sea Turtles, 32(4) Behav. 211, (Jan. 1, 1968); Robert S. Daniel & Karl U. Smith, The Sea-Approach Behavior of the Neonate Loggerhead Turtle (Caretta Caretta), 40(6) J. Compar. & Physiological Psych. 413 (Dec. 1947).

[20] See A. M. Granda & P. J. Oshea, Spectral Sensitivity of the Green Turtle (Chelonia Mydas Mydas) Determined by Electrical Responses to Heterochromatic Light, 5(2) Brain, Behav. & Evolution 143 (1972); D. H. Levenson et al., Photopic Spectral Sensitivity of Green and Loggerhead Sea Turtles, 2004(4) Copeia 908 (Dec. 15, 2004).

[21] See FWC Sea Turtle Lighting Guidelines (Dec. 2018), https://myfwc.com/media/18511/seaturtle-lightingguidelines.pdf.

[22] See Kurt W. Riegel, Light Pollution: Outdoor Lighting Is a Growing Threat to Astronomy, 179(4080) Sci. 1285, (Mar. 30, 1973).

[23] See Frans J. Verheijen, Photopollution: Artificial Light Optic Spatial Control Systems Fail to Cope with. Incidents, causation, remedies, 44(1) Experimental Biology 1 (1985).

[24] See Tim Hunter, The Birth of DarkSky (IDA) and a Lifelong Mission Fighting Light Pollution, DarkSky (Nov. 10, 2013), https://darksky.org/news/the-birth-of-ida-and-a-lifelong-mission-fighting-light-pollution/.

[25] See Paul W. Raymond, Univ. Cent. Fla., Sea Turtle Hatchling Disorientation and Artificial Beachfront Lighting (Ctr. for Env’t Educ. 1984).

[26] See Gary R. Mormino, Land of Sunshine, State of Dreams 322 (Univ. Press of Fla. 2008).

[27] See Condo Lights on Beaches Imperil Baby Sea Turtles, Fla. Today, July 16, 1983.

[28] See Llewellyn M. Ehrhart & Paul W. Raymond, Loggerhead (Caretta Caretta) and Green Turtle (Chelonia Mydas) Nesting Densities on a Major East-Central Florida Nesting Beach, 23(4) Am. Zoologist 963 (1983);

Llewellyn M. Ehrhart et al., Long-Term Trends in Loggerhead (Caretta Caretta) Nesting and Reproductive Success at an Important Western Atlantic Rookery, 13(2) Chelonian Conservation & Biology 173(Dec. 1, 2014).

[29] See Melbourne Causeway Bridge History, Wikipedia (Mar. 30, 2023, 7:31 UTC), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Melbourne_Causeway#Bridge_history.

[30] See Unnumbered Resolution of Brevard County Commission. August 5, 1982 (on file with the author).

[31] See Brevard County, Fla., Code § 85-15E (1985) (emergency ordinance related to the protection of sea turtles).

[32] See Blair E. Witherington, Human and Natural Causes of Marine Turtle Clutch and Hatchling Mortality and Their Relationship to Hatchling Production on an Important Florida Nesting Beach (1986) (M.S. thesis, University of Central Florida) (on file with STARS, University of Central Florida).

[33] See Video Interview with Blair E. Witherington, Senior Sea Turtle Conservation Biologist, Archie Carr Ctr. for Sea Turtle Rsch., Univ. of Fla. (Dec. 13, 2023) (available from authors).