No Net Loss? Sea Turtles & Contemporary Fisheries Management

No Net Loss? Sea Turtles and Contemporary Fisheries Management

Part I: Federal & State Turtle Excluder Device Regulations

Thomas T. Ankersen, Professor Emeritus

Katherine Pearson, J.D. Candidate

University of Florida Levin College of Law

Introduction

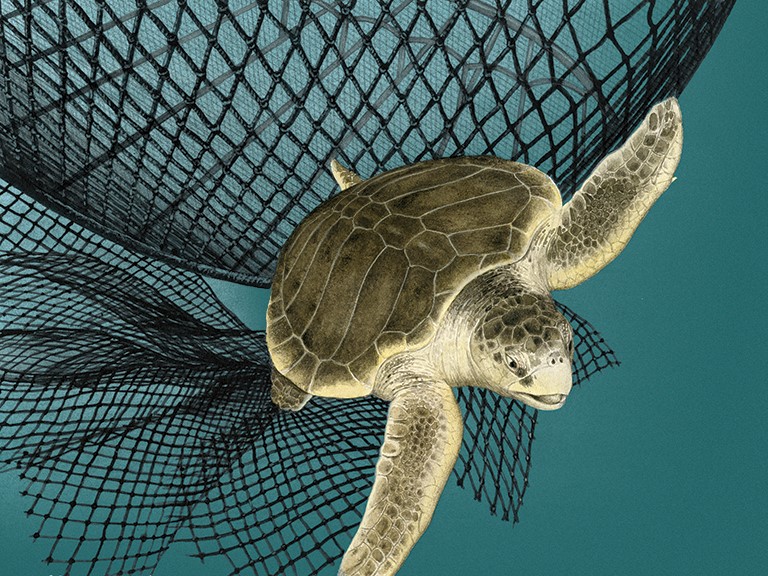

Even though the 1970s spelled the end for sea turtles as a targeted fishery, fisheries remained at the forefront of the immediate threats faced by the newly listed protected species. However, instead of being the target of commercial fishing, sea turtles were considered “bycatch,” the unwanted species that are caught alongside targeted species. Most often, bycatch is associated with net fishing, but it also occurs in “long-line fishing.” Sea turtles are bycatch in both practices, usually resulting in their mortality. With all species of sea turtles listed as endangered or threatened by the mid-1970s, attention quickly turned to the bycatch issue—first in the commercial shrimp fishery, and then in the gill net and long-line fisheries. Part I of this segment focuses on shrimp trawling, where the development of “Turtle Excluder Devices” represents another chapter in the decades-long story of sea turtle biology and the evolution of technology. Part II addresses Florida’s gill net fishery, a messy story of politics and policy that ended in an eventual ban of the practice. Part II also describes the less controversial elimination of long-line fishing in Florida waters.

Trawl Nets and Sea Turtle Mortality: The Need for Turtle Excluder Devices

While sea turtles actively swim, they must resurface to catch their breath.[1] However, doing so can be nearly impossible once they become trapped by nets, often leading to their drowning. In the late 1970s, growing attention was brought to these issues as deceased but seemingly healthy sea turtles were increasingly found washed up on coastal shores.[2] Early studies indicated that many of these deaths were due to net entrapment, especially by trawling nets used in the shrimping industry.[3] An observational study in 1977 reported on sea turtle behavior when encountering shrimp trawls and concluded that the species was unlikely to successfully outswim trawls or escape from trawls due to entanglement in the netting.[4] These findings coincided with the listing of green, hawksbill, Kemp’s ridley, leatherback, and loggerhead sea turtles under the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA), which prohibited the “taking” of any endangered species, lending urgency to the effort to find a solution that protected sea turtles while minimizing the impact on commercial fisheries. Two approaches were pursued. One would reduce “trawl time,” the amount of time a net remained submerged, such that a captured sea turtle could be released before drowning. The other involved the development of a technology to allow sea turtles to escape the trawl net, while retaining most of the target species, especially shrimp. To mitigate the entrapment issue, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) focused on a solution that prevented turtles from entering trawling nets without significantly reducing the number of caught shrimp.[5]

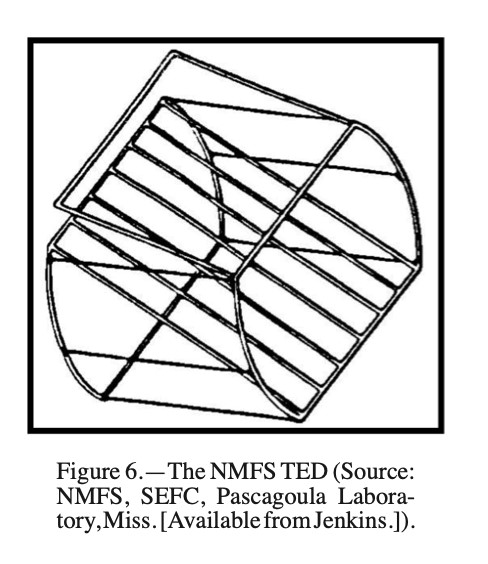

Initial development efforts kicked off in 1976 and were inspired by a video of sea turtles encountering a trawling net with a large mesh panel that allowed shrimp to pass through to the net bag but diverted the turtles out through an opening.[6] After consulting with sea turtle specialists, Archie Carr and Larry Ogren, it was determined that the mesh material still posed a threat of entanglement, so NMFS experimented with barrier panels to block turtles from entering the net.[7] The “forward barrier” design proved unsuccessful as it only reduced turtle capture by 30% while allowing 38% to 53% of shrimp to escape.[8] By 1979, developers converted this design into a “reverse barrier,” which reduced turtle capture by 79%.[9] However, a design defect allowed for shrimp to continue to escape the net, reducing shrimp capture by 15% to 30%. Shrimpers were unwilling to add weights to the gear to mitigate the issue.[10]

In 1980, after limited success installing webbed panel separators in trawling nets, the University of Georgia, Marine Extension Service suggested that NMFS consider incorporating jellyfish excluder technology.[11] Using this information, the Turtle Excluder Device (TED) prototype was conceived.[12] The original TED weighed 97 pounds and excluded 89% of turtles and an insignificant amount of shrimp.[13] This design was altered to allow turtles to escape from the top of the device rather than the bottom, which further increased exclusion rates to 97%.[14] In 1981, NMFS tested this design against trawls without TEDs and found that shrimp catches either increased or were not statistically impacted.[15]

It appears that indigenous knowledge and traditional field biology also played a key role in TED development. According to one source, it was a collaboration between a biologist at Cumberland National Seashore near the Georgia-Florida Border and a legendary netmaker from Nassau County, Florida, that yielded the refinements to the TED design that accommodated the sea turtle’s innate biological instinct to push up from the net to escape.[16] For his role in the development of TEDs, NOAA conferred its 2000 “Environmental Hero” award on third-generation netmaker Billy Burbank III.[17] And in 2014, he received the Florida Folk Heritage Award for his contributions to the art of net making.[18]

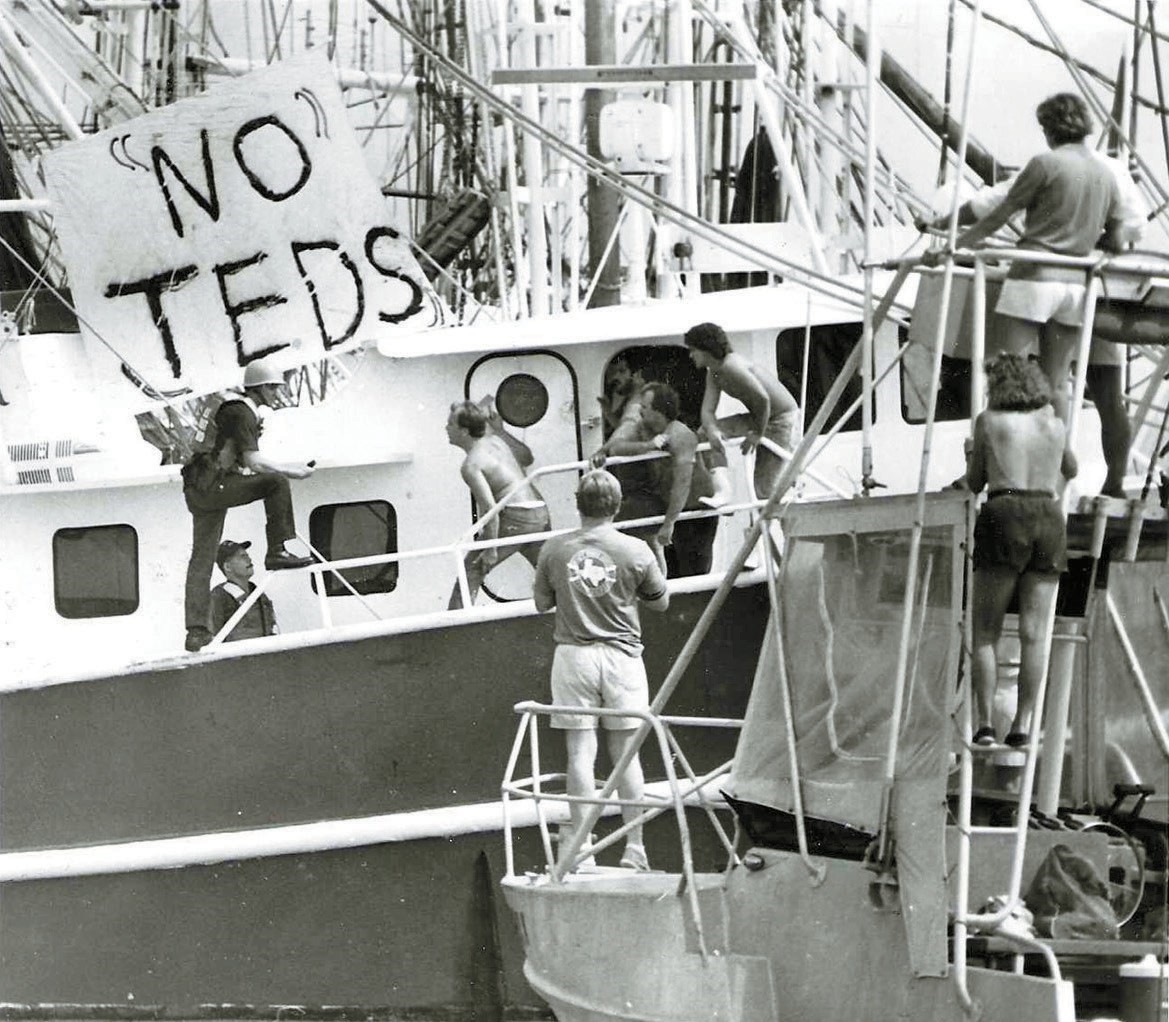

By 1981, NMFS introduced a voluntary program to outfit shrimp trawlers with TEDs.[19] Yet, the devices did not find popularity in the fishing industry, with many complaints about their size and weight.[20] After further research and development, TEDs were decreased in size and weight.[21] Despite these improvements and scientific findings that TEDs effectively reduced finfish bycatch as well as sea turtle bycatch, the new devices remained unpopular.[22] It was clear that many shrimpers would not use TEDs unless they were required.

Federal Turmoil and State Progress

To jumpstart the development of federal TED regulations and avoid potential lawsuits under the ESA, NMFS initiated federal mediation between delegates of the shrimping industry and interested environmentalists.[23] This effort culminated in 1987 when NMFS published a final federal rule that required commercial trawlers over 25 feet in length to use TEDs in offshore waters of the Southeast and trawlers under 25 feet to operate under reduced tow times during certain times of the year (“1987 Sea Turtle Regulations).[24] Implementation was stalled by lawsuits, injunctions, and a 1988 amendment to the ESA that prevented the Secretary of Commerce from carrying out the 1987 Sea Turtle Regulations until May 1989.[25]

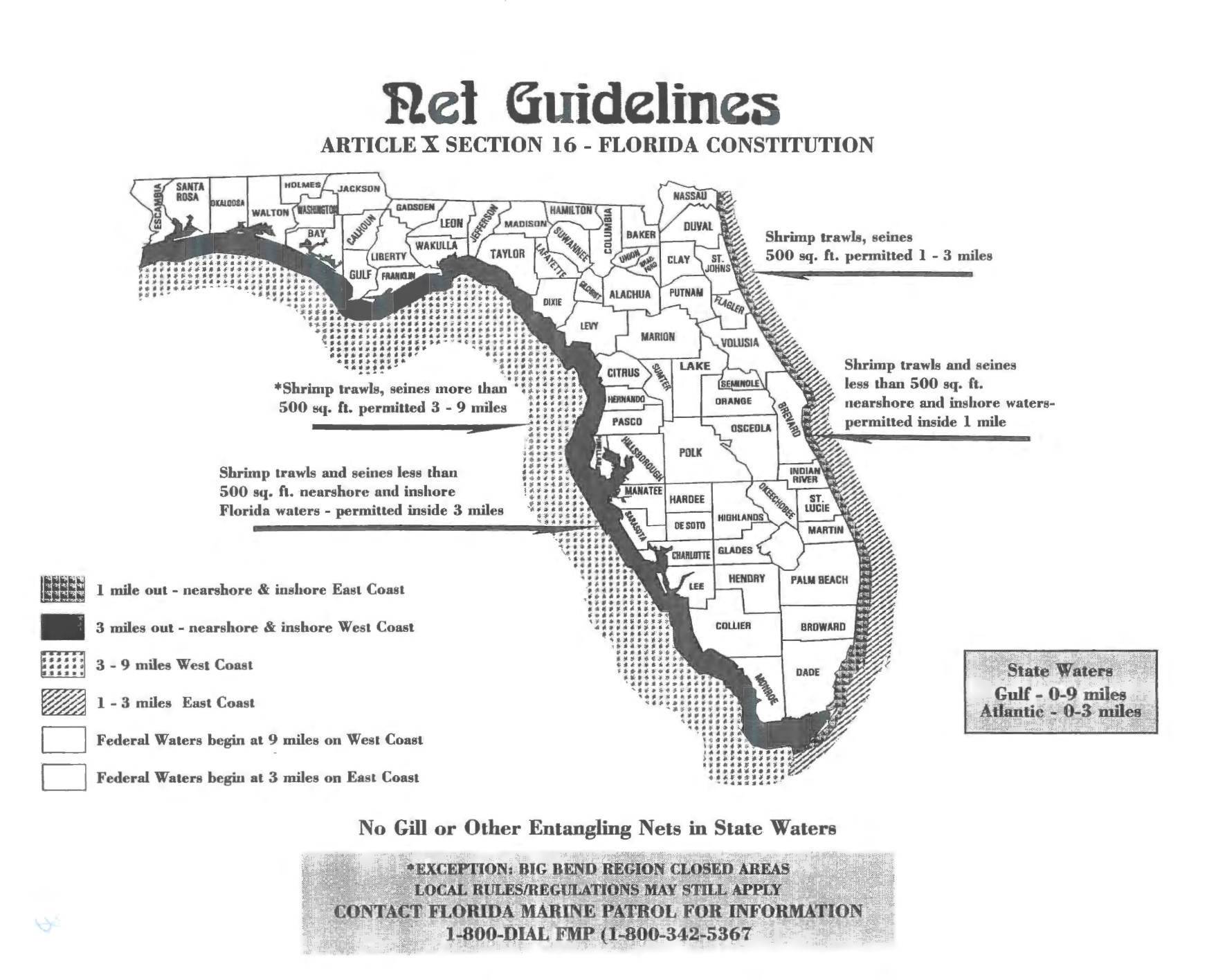

While implementation of the 1987 regulations was stalled in Washington, D.C., a handful of states were taking matters into their own hands, including Florida. In January 1989, the Florida Marine Fisheries Commission (“Commission”) passed an emergency rule restricting trawling times and requiring shrimpers to implement TED usage in State waters by February 1989.[26] (In Florida, State waters extend three miles into the Atlantic and nine miles into the Gulf of Mexico, while federal waters extend 12 miles from the Coast). Back in the federal capital, the Commerce Secretary reacted to reports of heightened numbers of stranded turtles over the winter months in Florida and southern Georgia. Deciding that these southern turtle populations could not wait until May 1989 for the 1987 Sea Turtle Regulations to go into effect, the Commerce Secretary implemented an emergency rule requiring fishermen in waters off northern Florida and southern Georgia to use TEDs.[27] After a 60-day grace period following the end of the congressional pause, the 1987 final Sea Turtle Regulations went into effect on June 30, 1989.[28]

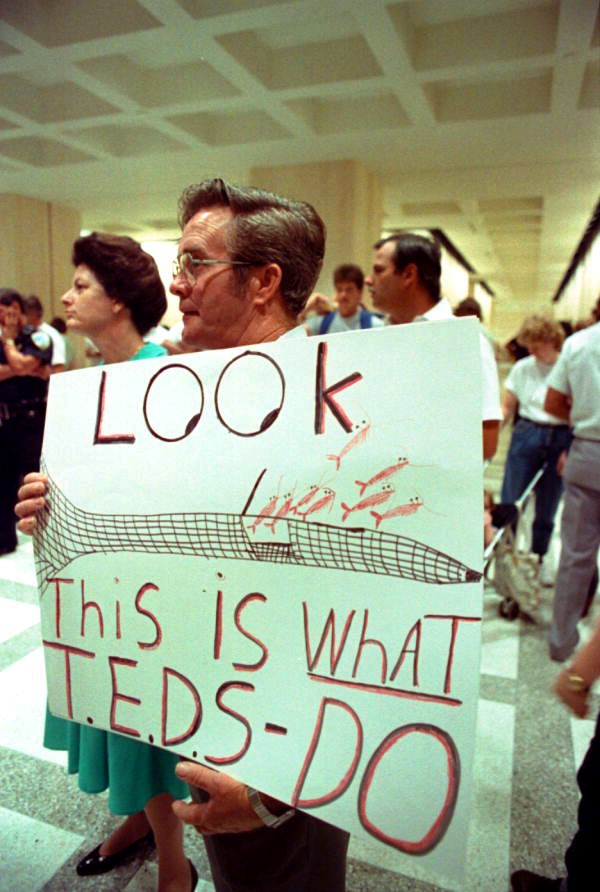

Meanwhile, in Florida, the Marine Fisheries Commission published a rule proposal on July 7, 1989, requiring the use of TEDs in all Florida waters throughout the year.[29] A public hearing for this rule was set for August 3, 1989.[30] Back in D.C., only ten days after the 1987 Sea Turtle Regulations went into effect, the Eighth District of the United States Coast Guard stopped enforcing the regulations, citing issues with sargassum, a seaweed, that made trawling with TEDs difficult.[31] By July 20, 1989, the Commerce Secretary resumed enforcement.[32] In the following month, shrimpers in various Gulf ports protested the regulations by creating blockades and burning TEDs.[33] After meeting with representatives of the shrimpers, the Commerce Secretary suspended enforcement for 45 days.[34]

While the suspension provided a reprieve from the protests and blockades, the Commerce Secretary was under pressure from the National Wildlife Federation, South Carolina Wildlife Federation, and Florida Wildlife Federation, who filed suit against the Commerce Secretary for suspending the regulation.[35] On August 3, 1989, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia held that the Commerce Secretary must either resume enforcement of the 1987 Sea Turtle Regulations or immediately introduce interim rules.[36] The Commerce Secretary promptly introduced a 30-day interim rule allowing shrimpers to either continue using TEDs or reduce their trawling times to 105-minute periods.[37]

Back in the sunshine state, the public hearing for Florida’s proposed TED regulation, which was scheduled for August 3, 1989, was stalled by a rule challenge filed by the Florida chapter of Concerned Shrimpers of America, Inc.[38] This obstacle, combined with the lack of stable federal protections, culminated in the Marine Fisheries Commission’s passage of an emergency rule on August 9, 1989.[39] Concerned with the estimates of drowned sea turtles in southeastern waters and the ineffectiveness of reduced trawl times, the Commission mandated TED usage in all state waters.[40] With sea turtles temporarily protected, the Commission could return to designing permanent regulations. Following a public hearing, the Commission made minimal changes to the language of the proposed rule.[41]

A day after the emergency rule was effective, on August 10, 1989, Shrimper David Davis was cited in Florida waters for not using a TED while trawling.[42] Instead of paying the fine, Davis filed with the county court to have the charge dismissed, claiming that the emergency rule exceeded the statutory authority of the Marine Fisheries Commission.[43] The county court and the First District Court of Appeal agreed with Davis, finding the rule invalid, but on February 15, 1990, the Florida Supreme Court reversed these findings, holding that the Commission’s rule was within its statutory authority.[44]

While Florida was waiting for the State Division of Administrative Hearings (D.O.A.H.) to rule on the proposed rule’s validity, the federal interim rule that allowed for either reduced trawl times or TED usage expired. Upon expiration of this interim rule, the Commerce Secretary reimplemented the 1987 Sea Turtle Regulations on September 13, 1989.[45] Back in Florida, without a ruling from D.O.A.H., the Commission renewed the State’s emergency rule on November 3, 1989, extending the ban on trawling without TEDs indefinitely.[46] On June 11, 1990, Florida’s TED regulation finally went into effect, and Florida officially had a permanent year-round TED requirement in State waters.[47] While the precise specifications for TED devices have continued to develop over the years, the prohibition against trawling without TEDs has remained firm.

International Shrimp Import Ban

While federal and state regulators grappled with TED implementation in U.S. and Florida waters, federal legislators sought to protect domestic shrimpers from unregulated, and therefore cheaper, foreign shrimp imports. On March 17, 1987, a U.S. House bill to amend the ESA to prohibit the “importation of shrimp and shrimp products from certain countries whose shrimping activities result in the incidental taking of threatened or endangered species” (“Section 609”) was introduced.[48] The first section of Section 609 instructed the Secretary of State to begin discussions with foreign nations to establish treaties aimed at protecting sea turtles and to provide updates to Congress regarding these negotiations.[49] The second prohibited the import of shrimp from countries that had not taken steps to protect sea turtles.[50] This bill was enacted on November 21, 1989.[51] On January 10, 1991, the Department of State published the guidelines that would be used to determine whether a specific foreign nation would be prohibited from importing shrimp.[52] Additionally, the Department of State determined that these requirements would only apply to countries in the “wider Caribbean,” which included Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, Venezuela, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, and Brazil.[53] These countries were given three years to adopt legislation comparable to the United States to be eligible to import shrimp to the United States.[54]

On December 29, 1995, the United States Court of International Trade ruled that by limiting the implementation of this statute to “wider Caribbean” countries, the federal government was failing to fully enforce Section 609.[55] Moreover, the court ordered that Section 609 must be applied to all foreign countries by May 1, 1996.[56] On April 19, 1996, the Department of State promulgated guidelines that expanded analysis criteria to all foreign countries.[57] This legislation and court ruling greatly leveled the playing field for Florida shrimpers, as they no longer had to compete in the marketplace against shrimpers who were not bound by TED regulations at the state and federal levels. Since 1996, the Department of State has issued an annual list of certified shrimp importers in the Federal Register, with the latest (2024) permitting 41 nations to sell shrimp in U.S. markets.[58]

After facing domestic challenges, foreign countries attacked Section 609 under international trade law. On October 8, 1996, India, Malaysia, Pakistan, and Thailand filed a complaint against Section 609 with the World Trade Organization, claiming that it violated the 1994 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT).[59] While the WTO upheld environmental protection as a legitimate basis to restrict trade in appropriate circumstances,[60] the WTO Dispute Settlement Body Panel, nonetheless, found that Section 609 violated the 1994 GATT because the analysis to determine importer eligibility was not equally applied amongst countries.[61] In 2000, Malaysia challenged the United States’ approach to compliance with the 1998 WTO Panel decision; however, the appellate panel found that the United States’ approach properly addressed any unfair discrimination.[62]

Expanding & Updating Regulations

The 1987 federal Sea Turtle Regulations enforced TED usage in specific waters during the summer months of each year, coinciding with nesting season.[63] However, turtle drownings were not isolated to summer months, which was evidenced by reports of strandings in winter months in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina.[64] To address this issue, the Secretary of Commerce implemented a rule on September 4, 1991, expanding TED requirements in offshore waters and applying trawling duration limits in Atlantic waters along the coasts of southeastern states, including Florida, until April 30, 1992.[65]

To extend these year-long restrictions, NMFS proposed a rule on April 30, 1992.[66] After analyzing comments from the proposed rule, NMFS enacted an interim rule on September 8, 1992, requiring that shrimp trawlers in the Atlantic Area must adhere to TED regulations year-round, and shrimp trawlers that restrict their trawl times as an alternative to using TEDs must not tow for more than 75 minutes at a time.[67] On December 4, 1992, the final rule was introduced, which extended the year-long regulations in the Atlantic Area to the Gulf Area as well.[68] Additionally, the rule provided that the vast majority of shrimpers would henceforth have to utilize TEDs, eliminating the restricted trawl time alternative.[69] To minimize disruptions and allow time for adherence, the rule introduced a phase-in program for shrimpers that were switching from restricted trawl times to TEDs.[70]

Conclusion

Since the turn of this century, the core principles of state and federal TED regulations have remained consistent. Amendments to these rules have largely been driven by the need to revise regulatory language to permit new TED technology. While the implementation of these regulations at the state and federal levels may have been tumultuous, studies suggest that they have been successful. It is conservatively estimated that sea turtle mortality rates via bycatch have decreased by 94% since 1990.[71]

References

[1] Peter L. Lutz & Timothy B. Bentley, Respiratory Physiology of Diving in the Sea Turtle, 1985 Copeia 671, 671-79 (1985).

[2] Interview by Stacey Gallagher with Barbara Schroeder, National Sea Turtle Coordinator, NOAA Fisheries (Dec. 8, 2023).

[3] History of Turtle Excluder Devices, NOAA Fisheries (Feb. 24, 2025), https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/southeast/bycatch/history-turtle-excluder-devices.

[4] Ogren et al., Loggerhead Sea Turtles, Caretta caretta,Encountering Shrimp Trawls, 39(11) Marine Fisheries R. 15, 17 (1977).

[5] History of Turtle Excluder Devices, NOAA Fisheries (Feb. 24, 2025), https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/southeast/bycatch/history-turtle-excluder-devices.

[6] Lekelia D. Jenkins, Reducing Sea Turtle Bycatch in Trawl Nets: a History of NMFS Turtle Excluder Device (TED) Research, 74(2) Marine Fisheries R. 26, 27 (2012).

[7] Id.

[8] Id. at 28

[9] Id.

[10] Id.

[11] Id. at 30

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Id.

[15] Id.

[16] From Dead Turtles to TEDs: A 20-Year Fight to Save Sea Life, Fernandina Observer (Mar. 10, 2025), https://www.fernandinaobserver.org/stories/from-dead-turtles-to-teds-a-20-year-fight-to-save-sea-life,48197.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] History of Turtle Excluder Devices, NOAA Fisheries (Feb. 24, 2025), https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/southeast/bycatch/history-turtle-excluder-devices.

[20] Id.

[21] Id.

[22] Id.

[23] Id.

[24] Sea Turtle Conservation; Shrimp Trawling Requirements, 52 Fed. Reg. 124, 24244 (Jun. 29, 1987).

[25] History of Turtle Excluder Devices, NOAA Fisheries (Feb. 24, 2025), https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/southeast/bycatch/history-turtle-excluder-devices; Sea Turtle Conservation; Shrimp Trawling Requirements Emergency Rule 54 Fed. Reg. 35, 7776 (Feb. 23, 1989); Sea Turtle Conservation; Shrimp Trawling Requirements, 54 Fed. Reg. 153, 32815 (Aug. 10, 1989). See also Sean Skaggs, Sea Turtles and Turtle Excluder Devices: A Review of Recent Events, 14 Wm. & Mary Envtl. L. & Pol’y Rev. 27 (1990).

[26] 15-3 Fla. Admin. Reg. (Jan. 24, 1989).

[27] Turtle Conservation; Shrimp Trawling Requirements Emergency Rule, 54 Fed. Reg. 35, 7773 (Feb. 23, 1989).

[28] Sea Turtle Conservation; Shrimp Trawling Requirements, 54 Fed. Reg. 153, 32816 (Aug. 10, 1989).

[29] 15-27 Fla. Admin. Reg. 12894 (July 7, 1989).

[30] Id.

[31] Sea Turtle Conservation; Shrimp Trawling Requirements, 54 Fed. Reg. 153, 32816 (Aug. 10, 1989).

[32] Id.

[33] Id.

[34] Id.

[35] Id.

[36] Id.

[37] Id.

[38] 15-33 Fla. Admin. Reg. 3608 (Aug. 18, 1989).

[39] Id.

[40] Id.

[41] 15-35 Fla. Admin. Reg. 3883 (Sept. 1, 1989).

[42] State v. Davis, 556 So. 2d 1104, 1105 (Fla. 1990).

[43] Id.

[44] Id. at 1108.

[45] Sea Turtle Conservation; Shrimp Trawling Requirements, 54 Fed. Reg. 176, 37813 (Sept. 13, 1989) (Interim expired on September 8, 1989).

[46] 15-44 Fla. Admin. Reg. 5147 (Nov. 3, 1989).

[47] 16-22 Fla. Admin. Reg. 2628 (Jun. 1, 1990).

[48] H.R. Con. Res. 1658, 100th Cong. (1987) (enacted).

[49] Earth Island Institute v. Christopher, 6 F.3d 648, 650 (Cal. Ct. App. 9th, 1993).

[50] Id.

[51] Shrimp Import Legislation for Sea Turtle Conservation, NOAA Fisheries (Sept. 10, 2021), https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/endangered-species-conservation/shrimp-import-legislation-sea-turtle-conservation.

[52] Turtles in Shrimp Trawl Fishing Operations Protection; Guidelines, 56 Fed. Reg. 7, 1051 (Jan. 10, 1991).

[53] Id.

[54] Id.

[55] Earth Island Inst. v. Christopher, 913 F. Supp. 559, 580 (Ct. Int’l Trade 1995)

[56] Id.

[57] Revised Notice of Guidelines for Determining Comparability of Foreign Programs for the Protection of Turtles in Shrimp Trawl Fishing Operations, 61 Fed. Reg. 77, 17342 (Apr. 19, 1996).

[58] Annual Determination and Certification of Shrimp-Harvesting Nations, 89 Fed. Reg. 113, 49254 (Jun. 11, 2024).

[59] Richard Mills, U.S. Wins WTO Case on Sea Turtle Conservation, Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (Jun. 15, 2001), https://ustr.gov/archive/Document_Library/Press_Releases/2001/June/US_Wins_WTO_Case_on_Sea_Turtle_Conservation.html; United States – Import Prohibition of Certain Shrimp and Shrimp Products, WTO, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds58_e.htm (last accessed Mar. 17, 2025).

[60] See generally Susan L. Sakmar, Free Trade and Sea Turtles: The International and Domestic Implications of the Shrimp-Turtles Case, 10 Colo. J. Int’l Envtl. L. & Pol’y 345 (1999); Jackson F. Morrill, A Need for Compliance: The Shrimp Turtle Case and the Conflict Between the WTO and the United States Court of international Trade, 8 Tul. J. Int’l & Comp. L. 413 (2021).

[61] Id.

[62] Id.

[63] Sea Turtle Conservation; Shrimp Trawling Requirements, 52 Fed. Reg. 124, 24244 (Jun. 29, 1987) (An exception to this rule was in the Cape Canaveral Area of Florida, where TEDs were required year-round).

[64] General Provisions; Threatened Fish and Wildlife; Extension of Applicability of Sea Turtle Conservation Requirements for Shrimp Trawlers off the Southeastern Atlantic Coastal States, 56 Fed. Reg. 171, 43714 (Sept. 4, 1991) (After the implementation of this rule, it stood that TED regulations were in effect in inshore and offshore waters in the Gulf Area between March 1 and November 30, in the Atlantic Area between May 1 and August 31 (this applies to typical years, but the prohibitions temporarily extended from September 1991 to April 30, 1992), and year-round in the Canaveral and Southwest Florida Area).

[65] Id.

[66] Threatened Fish and Wildlife; Threatened Marine Reptiles; Revisions To Enhance and Facilitate Compliance With Sea Turtle Conservation Requirements Applicable to Shrimp Trawlers; Restrictions Applicable to Shrimp Trawlers and Other Fisheries, 57 Fed. Reg. 84, 18446 (Apr. 30, 1992).

[67] Threatened Fish and Wildlife; Threatened Marine Reptiles; Revisions To Enhance and Facilitate Compliance With Sea Turtle Conservation Requirements Applicable to Shrimp Trawlers; Restrictions Applicable to Shrimp Trawlers and Other Fisheries, 57 Fed. Reg. 174, 40861 (Sept. 8, 1992).

[68] Threatened Fish and Wildlife; Threatened Marine Reptiles; Revisions To Enhance and Facilitate Compliance With Sea Turtle Conservation Requirements Applicable to Shrimp Trawlers; Restrictions Applicable to Shrimp Trawlers and Other Fisheries, 57 Fed. Reg. 234, 57351 (Dec. 4, 1992).

[69] Id.

[70] Id.

[71] Elena M. Finkbeiner et al., Cumulative estimates of sea turtle bycatch and mortality in USA fisheries between 1990 and 2007, 144(11) Biological Conservation, 2719, 2723 (2011).