Velador Newsletter

Velador Newsletter

Past Issues

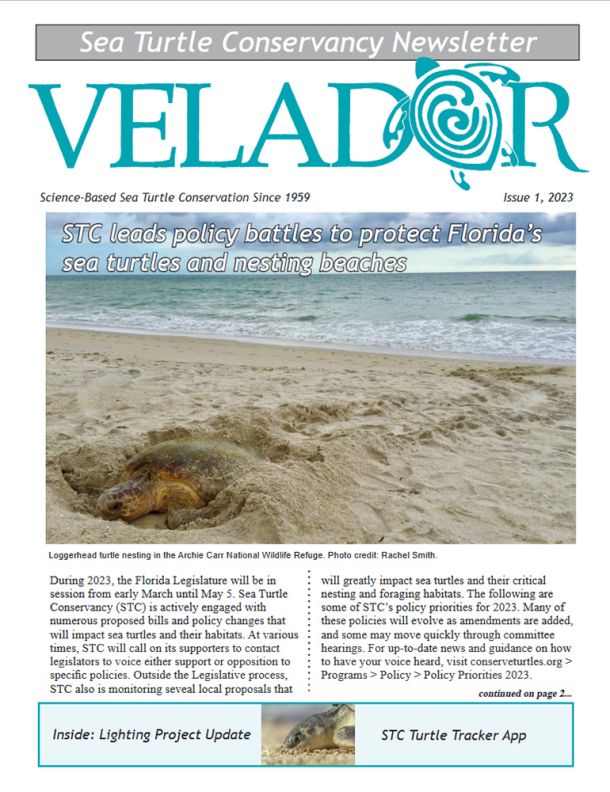

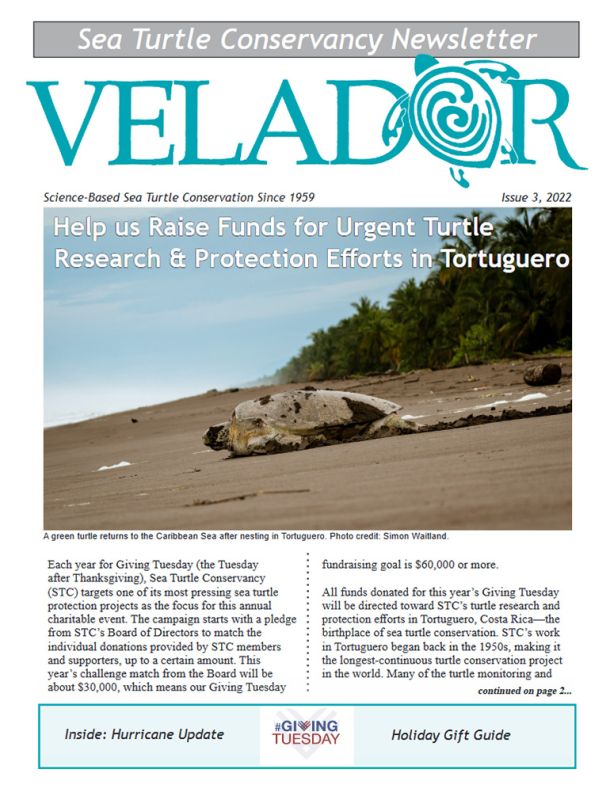

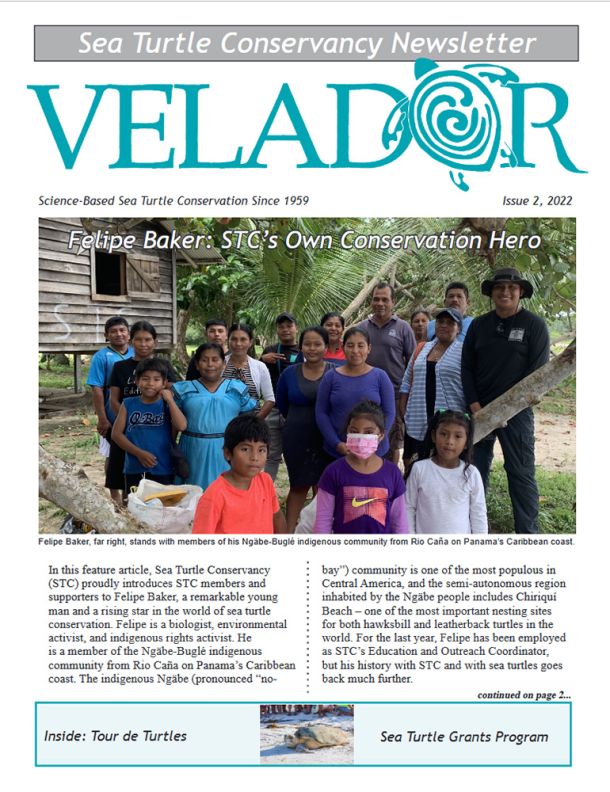

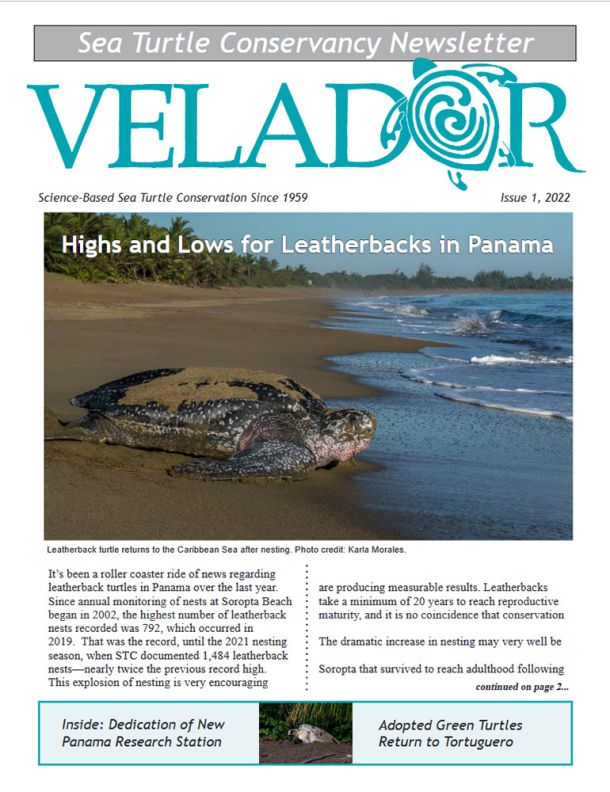

This section of our website features archived PDFs of the Velador, the official Newsletter of the Sea Turtle Conservancy (STC). In Caribbean cultures, Velador translates as “one who stands vigil” — referring to turtle hunters who waited at night for turtles to come ashore. STC claims this title for its newsletter, and around the world STC’s researchers and volunteers are replacing poachers as the new veladors.

The Velador is published for Members and supporters of the nonprofit Sea Turtle Conservancy as part of their Membership Benefits. Join STC today and start receiving your own copy of the Velador.

All Product Reviews